As we point out elsewhere on this site (See Looking Back, Looking Ahead: Racial Differences in Time Frames), there are many important differences in the ways White people and people of color view race. For example, many White people look back at the past and think about how far we’ve come. Many people of color look toward the future, to a time when we will have reached racial parity, and think about how very far we have to go (Eibach and Erlinger, 2006).

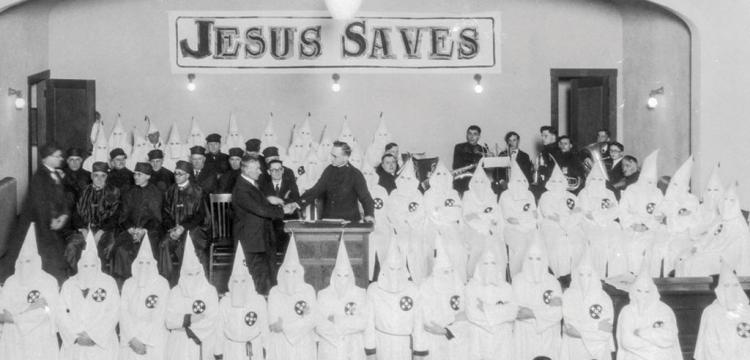

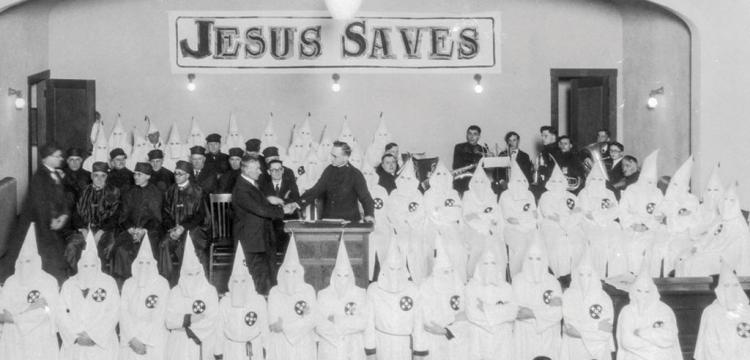

Beyond that, from what I’ve observed, White people and people of color also view the past differently. People of color, quite naturally, are horrified by the past. They take it personally, and often re-live it vicariously through family stories. White people, to the extent they think about it at all, have a distant, muted response. Most White people express a dispassionate disapproval, a tut-tutting, if you will, about events they perceive as . . well . . unfortunate. They think about slavery and the racial terror that followed rather like they think about old-time medical practices, like using leeches to suck blood from sick people—ill-advised, certainly, but unworthy of serious reflection, and unrelated to life today.

What would it take, then, for White people to acknowledge the violent, brutal, racist exploitation at the very heart of colonialism in the U.S. and around the world? (See Race = Racism.) Prof. James Q. Whitman of Yale Law School has one answer to that question. In Hitler’s American Model: The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law, Whitman argues that as the Nazis were developing the Nuremberg Laws in the 1930s (the first steps toward formalizing discrimination against Jews), they were inspired by the many useful ideas they found in U.S. history, law, and social practice.

Continue reading “Hitler’s American Model–and What That Means for Race in the U.S. Today”