We live in a big country. With 330 million people spread across 3.5 million square miles, we are the third-most populous nation, and the third-largest in size. A nation almost entirely of immigrants, there are people here from just about everywhere else. I can’t tell you the number of times I have visited someplace and been told by the locals, “This is the most diverse census tract in the whole country.” One in eight residents of this nation was born somewhere else. That is not a record, being slightly lower than the percent of foreign-born residents from 1860 – 1930, but it’s twice as high as the percentage in the memory of most American adults (Gibson and Lennon, 1999).

Evidence of our cultural diversity is everywhere you look. Med schools, counseling departments, and MBA programs offer advice on working with people from other cultures. Schools are learning to teach a new, more diverse, generation. Churches are talking about their changing neighborhoods. Rapid changes in the electorate are leading politicians to re-think their best path to a majority of the votes.

Understanding culture is important, but it’s difficult, too, because culture affects everything about us. The American Behavioral Scientist published a special issue a few years back on “Ethnicity and Money,” including an article on differences in Latino and Anglo views of money and how best to spend it (Falicov, 2001). Its conclusions are illustrative of how embedded culture is in every aspect of our thinking. Latinos’ and Anglos’ economic practices are affected by differences in perceived obligations to the extended family, religious values, preferred balance of work and leisure, expectations for spending on gifts, and marital roles.

From Kindergarten classrooms to mainstream news reports, discussions of culture tend to focus on food, dress, and holidays—differences we can see—while ignoring the more important differences we can’t see, in values, relationships, and worldviews.

There is a tendency to exaggerate cultural differences, and to do so in a way that favors one’s own culture. To assume that difference is deficiency and that those who think and act differently are falling short. That’s what sociologists call ethnocentrism. Things get even trickier when culture lines up with race. Because we see race as much more important than it is, cultural differences between races take on an even more exaggerated quality, looming larger than they otherwise would. Add to the mix the stereotypes groups have of each other, and you have the potential for some situations that can be difficult to navigate. And that’s OK. Many people, especially those in the majority, don’t have much experience interacting with people from different backgrounds. But it’s a skill that can be learned, especially with motivation and experience. Of course you’ll stumble now and again, but everyone does. Respect, humility, and perseverance will get you where you need to go.

“The world in which you were born is just one model of reality. Other cultures are not failed attempts at being you; they are unique manifestations of the human spirit.”

—Anthropologist Wade Davis

Here are a few things to keep in mind as you deal with cultural differences across race.

Listen before you talk.

One fundamental lesson is to spend more time listening than talking. One good way to do that is by asking open-ended questions. After my wife and I moved North, some people wanted to know more about us and our background. I learned quickly that there are questions that I liked to answer and questions that made me want to hurt somebody. “What do you miss most about Tennessee?” was a good question because it allowed me to respond on my own terms, and assumed that there were good things about Tennessee that I naturally would miss. “Did you have indoor plumbing growing up?” was not so much a question as a truly ignorant stereotype; moreover, it tempted me to disparage my new hometown. I felt like saying that Nashville, a city of a million people, made this little berg look like something from the 12th century. Not the best way to make new friends in a new place.

Questions that allow you to listen empathically—to hear what others want to say, and on their own terms—give you a chance to connect with someone else, and often to discover important commonalities as well as differences.

You can’t be expected to know everything . . . but you don’t have to remain ignorant

I am privileged to teach students from across the country and around the world. I can’t know everything I’d like to know about the entire planet. I’ve made more than my share of mistakes, some of them embarrassing. The first time I taught someone from Pakistan, I didn’t understand when she said something about Urdu. It is an official language of a nation of 170 million people, and I didn’t know that at the time. The ethnic and cultural diversity of China has tripped me up on more than one occasion. Heck, one time a student from Reno had a duck—a near meltdown, mind you—when I said “Nevahda” rather than “Nevada.” I can’t possibly know everything I need to know, and neither can you. The good news about being ignorant, however, is that I get lots of practice saying, “I didn’t know that. Tell me more.”

Even though you can’t be expected to know everything, I believe that you can be expected to be learning something. If you are not meeting people from different backgrounds on a regular basis, your life is too insular. There is strong informal pressure in this country, especially for White people, to find ethnically homogeneous neighborhoods, schools, and churches. If you have succumbed to that pressure and you aren’t getting to know a broad range of people, find at least one avenue in which you can break out of your segregated social networks.

We are all acculturated people who view things from an acculturated perspective.

As has been noted many times before, it can be difficult to recognize our own cultural practices. That is especially true for people who have had little contact with other cultural groups (Peterson, 2004). Statistically, those in the minority know more people from other groups than majority-group members do. If you are one minority person in a group of ten, everyone else you talk to will be from the majority. If you are one of the nine majority members, eight of the other nine people you talk to will be from your own group.

Urban Segregation in the U.S. by Media Market

Given the remarkably high level of racial segregation in this country—apartheid-era South Africa was the only nation in the world more segregated than we are today (Massey, 2003)—it is not surprising that many White people have very little contact with those of other races and cultures. Without the opportunity to see first-hand how people from other groups think and act, we cannot notice how we differ from them. I have had White students, for example, who confessed disappointment that they don’t have a culture—their ethnic friends seemed to live such interesting lives, what with their culture and all. Of course, White people are part of a culture, with values and rituals and social expectations, but their culture can be so transparent to them that they can’t see it.

The insidious danger here is that there is a very small step from seeing yourself as culture-less to seeing yourself as “just normal” and, therefore, seeing yourself as the implicit standard by which other groups are to be compared, and judged. It doesn’t matter whether you see their culture as interesting and fun, or as deficient and maladaptive. An ethnocentric perspective makes it difficult for you to really understand either yourself or other people.

Appreciating cultural difference is not the same thing as stereotyping.

People who belong to a majority group sometimes are uncomfortable talking about culture and cultural differences. This is a result of two things, in my experience. The first, as we just saw, is being unaware of their own acculturation. The second is that they have learned very well the cautionary lessons against stereotyping. Talking about the collectivist orientation of most Asian cultures as against the individualistic bent of the West sounds to them like saying, “All Asians are like this, and all White people are like that,” and their stereotype sensors go off.

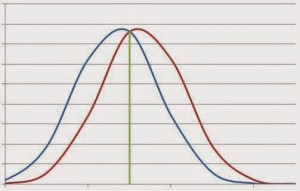

It is important to remember that while average cultural differences definitely exist, individual members of a culture can be found at any number of points along a continuum. Most of the time, cultural views can be represented by a bell curve, with lots of people toward the middle of their group, but a fair number on either side, too. Differences between cultures are like overlapping curves—the peaks are at different points on the line, but the tails overlap enough that you really can’t predict much about an individual member of either group.

For example, true to stereotype, White Americans do tend to be more culturally isolated than others in this country. It’s partly a function of being in the majority and partly a function of the fact that well-to-do White people craft their environments very carefully, almost always in ways that make them as segregated as possible. But that is by no means true of all Whites. A number of my White students went to high schools in which they were in the minority. A couple of them grew up in otherwise-all-Black churches. Quite a few lived overseas with parents whose work took them to other countries. Their experiences and perspectives are quite different from those of most White people, and assumptions others make about them are nearly always wrong. It’s the same with any group, obviously.

The Bottom Line: Differences in social culture form the horizontal dimension of understanding race. Just like your mother always told you, respect and good manners will go a long way in helping you connect with other people across a cultural divide.

I would like to cite this blog post. May I please have the author and date posted?

My apologies for the slow response. This page was published on October 19, 2014. The author is Charles W. Green, Professor of Psychology, Hope College, Holland, Michigan.

Thank you for your interest–

Charles Green

Hurrah, that’s what I was exploring for, what a data!

present here att this website, thanks admin of

this site.