racial progress

“Kelp was the key to America.”

That’s the opening line of Historian Pekka Hämäläinen’s Indigenous Continent: The Epic Contest for North America (2022). During the most recent ice age, so much water froze and turned into glaciers that the oceans shrank, leaving new dry lands around the world. What was—and is now again—the Bering Strait became Beringia, a swath of land twice the size of Texas connecting northeast Asia with northwest North America. It was filled with “the woolly mammoth, woolly rhinoceros (on the Siberian side of the land bridge), giant short-faced bear, scimitar cat, and Pleistocene camels, horses, bison and musk-oxen.”

Coming to America

over the last 20,000 years

A group of people with ancestors from both East Asia and Northern Siberia moved from Siberia into what is now Western Alaska. Approximately 75,000 years after the first homo sapiens left Africa, the “back door of human expansion” was opened and people entered the Western Hemisphere for the first time (Childs, 2018). Some of those people stayed in Beringia; others kept right on going.

There is still much we don’t know about how this hemisphere was populated. Archeologists and anthropologists, geneticists and ecologists are collecting new data all the time, offering new hypotheses and crafting new theories. Over forty years ago, Archeologist Knut Fladmark (1979) argued that the easiest and quickest way for people to move out of one tiny corner of the hemisphere and inhabit two entire continents would be by boat, down the Pacific Coast. (Fladmark noted that some Northeast Asian cultures had the equipment and skill to make such a trek.) There are “kelp forests” along much of the Pacific coastline with abundant fish and wildlife, providing sustenance just about all the way to Tierra del Fuego (Erlandson et al., 2015). The first Americans traveled this “kelp highway” with remarkable speed, building settlements along the way and establishing outposts for inland exploration.

When many continental glaciers melted about 20,000 years ago, a land corridor opened up east of the Rockies that brought people into the interior of North America and on further east and south. The population boomed, growing sixty-fold in just 3,000 years. All the while adapting to incredible variations in climate, terrain, and food sources.

A “thriving, stunningly diverse place”

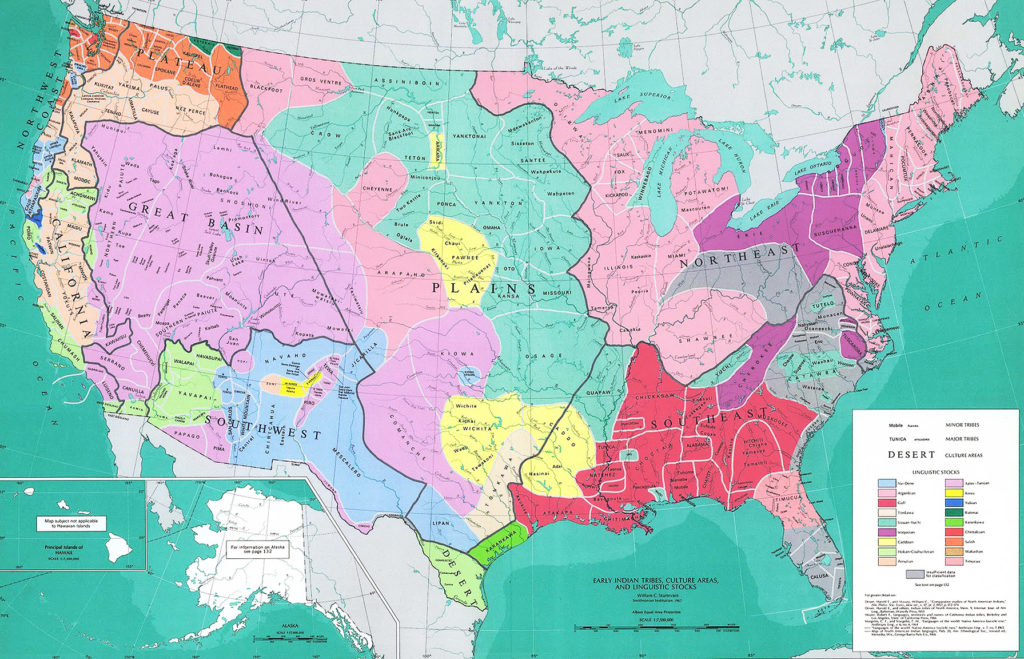

The result was a rich, impressive array of nations and cultures spread out across an entire hemisphere. Author Charles C. Mann (2005) says that by 1491 the Americas looked like this:

“At the time of Columbus the Western Hemisphere had been thoroughly painted with the human brush. Agriculture occurred in as much as two-thirds of what is now the continental United States, with large swathes of the Southwest terraced and irrigated. Among the maize fields in the Midwest and Southeast, mounds by the thousand stipped the land. The forests of the eastern seaboard had been peeled back from the coasts, which were now lined with farms. Salmon nets stretched across almost every ocean-bound stream in the Northwest. And almost everywhere there was Indian fire.

“South of the Rio Grande, Indians had converted the Mexican basin and Yucatán into artificial environments suitable for farming. Terraces and canals and stony highways lined the western face of the Andes. Raised fields and causeways covered the Beni. Agriculture reached down into Argentina and central Chile. Indians had converted perhaps a quarter of the Amazon forest into farms and agricultural forests–an area the size of France and Spain taken together.”

Historian Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz (2015) writes that there were approximately 100 million people in the Western Hemisphere in 1492, about 40 million of them in North America.1 In 1542, Bartolomé de las Casas, a conquistador who later entered the priesthood, said that the Americas were “a beehive of people,” and “it looked as if God has placed all of or the greater part of the entire human race in these countries” (Mann, 2005). There were many different societies across both continents, some small, some quite large. There was advanced agriculture, animal husbandry, political organization, medicine, science, transportation systems, cross-continental trade, and other hallmarks of advanced civilizations. Hämäläinen called the pre-Columbian Americas a land of “astounding human diversity and resilience.” And Mann’s description: Prior to colonization, the Western Hemisphere was a “thriving, stunningly diverse place, a tumult of languages, trade, and culture, a region where tens of millions of people loved and hated and worshiped as people do everywhere.”

European encounters

But then, of course, Columbus. And the untold number of European colonists who followed thereafter. (For the broad context of European colonization, please go here.) There are two aspects of colonization that pertain particularly to indigenous Americans: the debilitating effects of disease and the brutal nature of European warfare.

Disease

Prof. Dunbar-Ortiz says that in the two centuries after Columbus arrived, the indigenous population dropped by 90%, mostly from disease. That is a stunning figure, quite unprecedented in the modern era. There is evidence of a variety of European diseases; one of the most devastating was smallpox. Charles Mann says that it started in the Caribbean and “shot out like ghastly arrows . . . to every corner of the hemisphere, wreaking destruction in places that never appeared in the European historical record. The first whites to explore many parts of the Americas therefore would have encountered places that were already depopulated.” There is a name for this: The Great Dying. The deadly toll of European disease was a necessary pre-requisite for successful European settlements. It was an oft-repeated pattern. The Spanish failed to establish permanent colonies in Florida until the Native population had been decimated. The same thing happened in Brazil with the Portuguese and in Canada with the French.

Dunbar-Ortiz points out that not only did the population fall away; quite a bit of its infrastructure disappeared or fell to ruin. That was true of agriculture, too. Land management and cultivation declined. A tremendous reforestation ensued, resulting in a sizeable decrease in global levels of carbon dioxide. That led to the “little ice age” of the 17th century, the only significant period of global cooling in the last 2,000 years (Koch et al., 2019). White settlers often referred to Indian land as a “wilderness.” Part of that was due to their ethnocentric ideas about what “civilization” was supposed to look like. Part of it was an effort to downplay the fact that other people got there first. But part of it was due to the disintegration of Native infrastructure. There was more “forest primeval” in the Americas in 1850 than there was in 1650.

Violence

Whenever people from different cultures come into contact with each other, there is bound to be confusion and a certain amount of distress. I am amused by Charles Mann’s description of Europeans from an indigenous perspective:

“Shorter than the natives, oddly dressed, and often unbearably dirty, the pallid foreigners had peculiar blue eyes that peeped out of the masks of bristly, animal-like hair that encased their faces. They were irritatingly garrulous, prone to fits of chicanery, and often surprisingly incompetent at what seemed to Indians like basic tasks. But they also made useful and beautiful goods—copper kettles, glittering colored glass, and steel knives and hatchets—unlike anything else in New England. Moreover, they would exchange these valuable items for cheap furs of the sort used by Indians as blankets. It was like happening upon a dingy kiosk that would swap fancy electronic goods for customers’ used socks—almost anyone would be willing to overlook the shopkeepers’ peculiarities.”

Europeans were equally perplexed by indigenous people. Dealing with cultural difference was inevitable. But that was not the heart of their conflict. The crux of the matter was quite simple: Europeans wanted land that was already occupied, and they were willing to kill men, women, and children in order to take it.

Dunbar-Ortiz minces no words when she describes the violence inherent in colonization:

“Settler colonialism, as an institution or system, requires violence or the threat of violence to attain its goals. People do not hand over their land, resources, children, and futures without a fight, and that fight is met with violence. . . The notion that settler-indigenous conflict is an inevitable product of cultural differences or misunderstandings, or that violence was committed equally by the colonized and the colonizer, blurs the nature of the historical processes.”

Dunbar-Ortiz notes that centuries of perpetual war in Europe prepared the colonizers well for war with the indigenous peoples of the Americas. She calls the Crusades, the English conquest of Scotland, Wales, and Ireland, and numerous other conflicts “dress rehearsals” for invading the Western Hemisphere. One example: the English paid bounties to Scots and Welsh settlers in Ireland for the heads of dead Irishmen. As a matter of efficiency, they later required only the scalps for payment.

The British brought this practice to North America, paying for the scalps of Indians murdered by settlers when they wanted to move into new territory. For example, in November of 1755, Spencer Phips, the lieutenant governor of the Province of Massachusetts Bay, offered a reward worth $12,000 in today’s money to colonists who would bring in the scalp of a Penobscot man. The scalp of a Penobscot woman was worth $6,000; the scalp of a Penobscot child was worth almost as much. Sometimes those who killed Indians were given the land occupied by those they had murdered, no doubt worth even more than the bounty.2 The practice continued until nearly 1900 as settlers pushed west. The name given to the mutilated bodies after they had been scalped? Redskins.

We are more aware of Native history than we used to be—I never studied the Jacksonian “trail of tears” in school, for example, even though I lived just a few miles from a reservation in Kansas created for Potowatomi people driven out of Michigan.3 But we still don’t comprehend the violence. Dunbar-Ortiz quotes a Georgia man who helped evict Cherokees in the 1830s. Later in life, he said:

“I fought through the civil war and have seen men shot to pieces and slaughtered by thousands, but the Cherokee removal was the cruelest work I ever knew.”

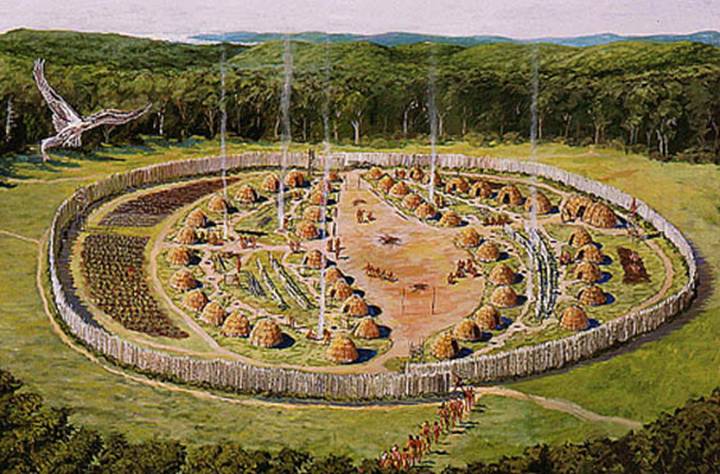

a walled Pequot village

The no-holds-barred, take-no-prisoners approach to warfare with Native Americans started early. The Pequot War in what is now Connecticut began in 1636, only sixteen years after the Mayflower arrived. It is best known for the Battle of Mistick Fort, also known as the Mistick (or Mystic) Massacre or the Pequot Massacre. There had been skirmishes between the Pequots and the English over land and trade, but this was a significant escalation. The English set fire to Mistick Fort (a Pequot village surrounded by a wooden fence) and stood in a circle, shooting anyone—man, woman, and child—who tried to escape. More than 400 people died in just one hour. In normal warfare, soldiers fight soldiers, and the killing of civilians is a war crime. But when you’re fighting for land, everyone has to be eliminated one way or another.

The single deadliest attack of Native people by the U.S. military was the Bear River Massacre in Idaho in 1863. Approximately 350 people were killed, about one-quarter of them women and children.

John Grenier (2005), an Air Force officer and a professor of history at the Air Force Academy, says that “Attacking and destroying Indian noncombatant populations remained Americans’, particularly frontiersmen’s, preferred way of waging war from the early sixteenth to the early nineteenth centuries.” These battles were marked by “extravagant violence.” They were “unrestrained struggles for the complete destruction of the enemy.” But why? Grenier says that “Most explanations for the Indian Wars’ brutality focus on racism. Americans’ racism toward Indians, however, did not solidify until the middle of the eighteenth century.” He argues, therefore, that White colonizers’ feelings about Indians stemmed from “the uncontrollable momentum of violence . . . Instead of racism leading to violence, in early America violence led to racism.” At some point, anti-Native violence became “a key to being a White American,” enabling “later generations of ‘Indian haters,’ men like Andrew Jackson, [to] turn the Indian wars into race wars.” We see, once again, that people need to justify the harm they do to others by believing that those people deserved it.

The violence was accompanied by broken treaties and outright lies about the settlers’ intent. Roger Nichols (2009), a scholar of history and American Indian Studies, says that Andrew Jackson’s secretary of war, John Eaton, was clear (though not with the Indians) that he considered all the treaties the government signed to be temporary measures, to be revoked when they were no longer convenient. About the same time, the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Indian Affairs referred to treaties as “empty gestures” designed to appease “the vanity of tribal leaders.” Even when tribes were offered farmland and support payments, they rarely received what they were promised. Corruption was rampant in the Department of Indian Affairs; it was common for bureaucrats and suppliers to make off with most of the money.

When we make a promise, it’s a promise to the Great Spirit, Wakan Tanka. Nothing is going to change that promise. We made all these promises with the white man, and we thought the white man was making promises to us. But he wasn’t. He was making deals.

— A Native elder, quoted by Kent Nerburn in Neither Wolf nor Dog

Prof. Dunbar-Ortiz notes that the federal government established the first Office of Indian Affairs in 1824; tellingly, it was located within the War Department. By 1869, six of the seven departments of the U.S. Army were stationed west of the Mississippi, scattered across hundreds of forts, built specifically to wage war against Indians. Troops were necessary because the government was giving land to White settlers—land it claimed but did not possess. The settlers had deeds, but they still had to fight for the land. Land was the equivalent of higher education today; those homesteads created income that, as it was passed along, became intergenerational wealth. How do I know? Because it happened to me.

“If Hollywood wanted to capture the emotional center of Western history, its movies would be about real estate. John Wayne would have been neither a gunfighter nor a sheriff, but a surveyor, speculator, or claims lawyer. The showdowns would occur in the land office or the courtroom; weapons would be deeds and lawsuits, not six-guns. Moviemakers would have to find some cinematic way in which proliferating lines on a map could keep the audience rapt.” Patricia Nelson Limerick, The Legacy of Conquest: The Unbroken Past of the American West

It took 400 years for Europeans to take control of North America. Pekka Hämäläinen argues that the Western Hemisphere was largely indigenous long after the first Europeans arrived. Europeans claimed the land that would become the U.S., but they didn’t rule most of it until well into the 19th century. We talk about Jefferson buying the Louisiana territory from France, but there was no meaningful sense in which France owned it. Jefferson bought France’s claim to the land, but that only meant that France wouldn’t fight us for it. It was 99% indigenous, and the U.S. would still have to fight the people who actually lived there.

“The contest for the continent was, in essence, a four-centuries-long war, that saw almost every Native nation fight encroaching colonial powers—sometimes in alliances, sometimes alone.”

Pekka Hämäläinen, Indigenous Continent: The Epic Contest for North America

In the end, after centuries of fighting to maintain their homes, their languages, and their way of life, Native Americans lost 98.9% of their land, and ended up in places that, on average, are less livable and less profitable than their original territories (Farrell et al., 2021). Charles Mann says that non-Native people continue to have a bifurcated, simplistic view of Indians, seeing them either as “incurably vicious barbarians” or as “noble savages.” Both stereotypes turn Indians into passive, ineffectual people stripped of agency, ideas, and personality, ultimately uninteresting and unworthy of respect. Such patently false stereotypes enable the rest of us to be both indifferent to Native history and complacent about how we continue to benefit from their exploitation.

Fighting Back

We’ve already noted the four centuries across which American Indians fought the slow encroachment of European control of the Western Hemisphere. But the fight isn’t over. Native Americans are incredibly active in advocating for their rights and promoting the general well-being. The Native American Rights Fund is the Native counterpart to the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. It works to protect voting rights, land rights, and Native interests in a variety of areas. There are Native organizations in business, health, education—just about any field you can imagine. Native Americans are active in many ways to protect the environment (see here and here, for example). There are quite a number of organizations that work for indigenous rights around the world. Native nations in the U.S are becoming increasingly financially secure, often thanks to casino revenues, and using their resources to improve health, education, housing, and job opportunities for Native Americans.

And there are individual Natives, of course, devoting themselves to making this country a better place. As a group, American Indians are proud of their high levels of participation in the military; veterans are honored participants in every pow wow, for example. Natives are increasingly represented in government at every level. Native women participate in “water walks” around the country to bring attention to the need for clean water. Several of them came through my hometown a few years back as they walked around Lake Michigan, stopping along the way to teach others about cleaning up the Great Lakes and the importance of environmental justice. Just everyday folk doing their part.

And a personal observation, if I may. At least in my neck of the woods, American Indians show the rest of us how to form a strong and inclusive community, clear about its identity while welcoming others, too. You see it at pow wows. They are in no way a performance for non-Natives. They are a community’s affirmation of heritage, tradition, belief, and care for one another. And yet everyone is invited. Many Native families are multiracial, and that is reflected in the diverse appearances of the drummers and dancers. It exemplifies that Native identity is both confident and hospitable. It’s a gift I wish the rest of us could receive.

There is so much more to say, obviously, about boarding schools, on-going discrimination against Indians, exploitation of Indian land, etc. If, like me, you would benefit from knowing more about the history and experiences of Native Americans, I encourage you to do these simple things:

- Read one of the books cited in this essay. Click on the links that are of interest to you. Watch a documentary. Attend lectures and presentations by Native speakers.

- Read—and support—Indian Country Today.

- Attend a pow wow near you (you can find one at powwows.com). Entry fees are low. Be sure to support the vendors. Get some fry bread, buy a book, or find a nice piece of jewelry. The vendors pay a fee to be there, one reason it doesn’t cost much to get in. They are making a living and promoting Native culture at the same time.

- Include at least one Native organization, such as First Nations Development Institute, in your charitable giving.

FOOTNOTES:

- Estimates of the population of the entire planet in 1500 range between 425 and 540 million.

- There is a documentary about this called Bounty. You can watch it here.

- Dunbar-Ortiz estimates that approximately 70,000 Native Americans who lived east of the Mississippi River were moved west in the 1830s. She uses the term “trails of tears” (note the plural) to emphasize how many people from how many places were forced from their homes.