The last post was about the rise in overt White racism over the last fifteen years or so. Interestingly, it has been accompanied by an increase in White support for antiracism, too—the backlash to the backlash. According to Civiqs, while 51% of White American adults oppose the Black Lives Matter movement, 37% support it. That doesn’t sound like much, but when you consider that 75% of White American adults opposed Dr. King in 1968, his final year of life, it’s a step, at least. There are several indicators that the number of White Americans concerned about racism is on the rise. Why might that be?

In How to Be an Antiracist (2019), Ibram X. Kendi asserts that while most White people want to be non-racist, that isn’t possible. Kendi says that we are either going along with the racism of the culture or we are actively working against it. To do nothing is to let racism take its course. We can pretend to be non-racist, but it isn’t actually possible. Kendi goes on to make the interesting assertion that racist and antiracist are not fixed identities that describe something fundamental, something essential, about a person, across time and place. Rather, racist and antiracist are behavioral descriptions of what we are doing at any given point in time. Kendi says, “We can be racist one minute and antiracist the next. What we say about race, what we do about race, in each moment, determines what—not who—we are.”

So, in this section on The View from Above, let’s examine how some White people come to embrace antiracism and how they can spend more and more of their time being antiracist.

How White people become aware of racism

If you ask most White people, “What is the cure for racism,” they’ll answer, “Education.” But it’s way more complicated than that.

Education can help, under the right circumstances. Bañales, Banks, and Burke (2021) offered incoming college students, all of them White, an opportunity to participate in a three-day antiracism workshop and found significant changes in students’ attitudes about race and racism. Helen Neville and her colleagues (2014) found a reduction in racism among White university students during their time in college if they took diversity-related courses, attended diversity events, and developed a racially diverse friendship network. Smith, Senter, and Strachan (2013) did a very similar study and found that while White men were more likely to hold racist attitudes than White women when they entered college, they were also more likely to be positively affected by diversity-related courses, experiences, and friendships during their time there.

But formal training doesn’t always make that kind of difference. Edward Chang and his colleagues (2019) found that diversity training did change participants’ attitudes, but not their behaviors, unless they were already pretty committed antiracists. Kalev, Dobbin, and Kelly (2004) found that educating managers about diversifying the workforce usually doesn’t result in a change in hiring practices. Don’t teach it, they recommend. Do it. Set up new procedures for hiring and for supporting people from under-represented groups—and be sure to identify the people responsible for making it happen. Onyeador, Hudson, and Lewis (2020) also say that traditional training often isn’t very effective; they suggest a variety of other options that work better. Remember, too, that antiracist efforts are always met with racist backlash. When people don’t want to attend a diversity event, but they have no choice (think of mandatory sessions in the workplace, e.g.), they may well walk away disgruntled and annoyed (Sanchez and Medkik, 2004).

To dive deeper into the effectiveness of diversity training, listen to this podcast from the American Psychological Association, featuring social psychologist Calvin Lai.

Given the mixed results of formal training, I think we need to consider a broader definition of education for those of us moving toward antiracism. Not only seats in seats for half a day with a break for bad coffee and stale muffins, but all the ways we learn, unlearn, and re-learn in life. Think about the college students in the studies I just mentioned who became more antiracist during their time in school. They took classes, yes, but they also joined organizations and developed new friendships. Changing long-held beliefs and values has to engage the whole brain, not just the cerebral cortex.

Sociologist Jacob S. Rugh of Brigham Young University wrote an open letter to the BYU Committee on Race, Equity, and Belonging, expressing his concerns about racism on campus. Prof. Rugh is a scholar of racism, but in his letter, he did not cite statistics or describe his research. He focused, instead, on his relationships with students of color at the university and his concern for their well-being. Writing from his heart, his letter speaks of the anguish of people he has come to know and respect. He cares about racism, in part, because he cares about the people who are hurt by it.

I can relate. I have studied race and racism for over forty years, but it isn’t all head knowledge for me, either. It’s listening to students, colleagues, and friends who have been treated in ways they did not deserve. It’s learning that people in power who are supposed to respond to racist events often would rather just explain them away, and then threaten those who refuse to go along. Some of my White students who understand racism well, and care deeply about it, have an adopted sibling of color. They are appalled by the terrible ways their sister or brother has been treated. I am convinced that racism depends on the extreme isolation of White people, resulting in both ignorance and apathy. Every White person I have ever known who broke out of the isolation, who truly cared about a person of color, was deeply concerned about racism and committed to antiracism. If you are White and stuck inside White spaces, you’ve got to do something about that. If you don’t know what else to do, start with social media, where you can learn from people who don’t experience the world in the same way you do. From there, you’ll get some ideas about next steps you can take.

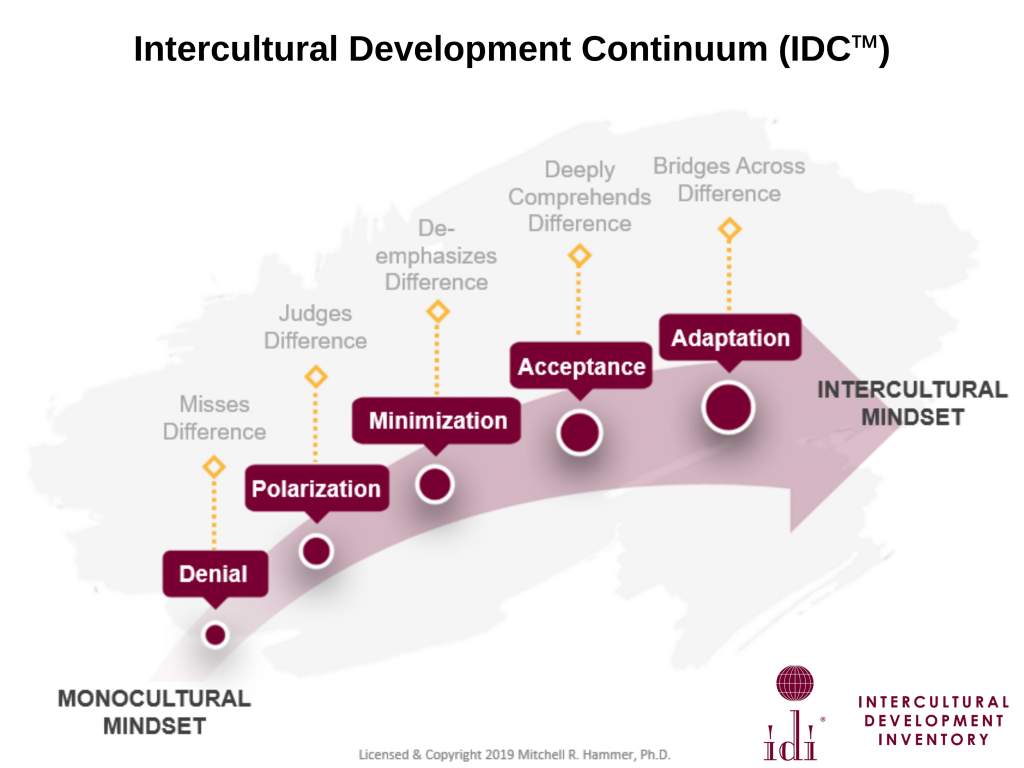

There are a variety of models that describe the growth of dominant group members in overcoming their ethnocentrism. One is the Intercultural Development Inventory, which proposes these stages of development. Of course, many people get stuck in one stage and never move on, but among those who do, this is a common trajectory:

You can read more on their website, but here’s a quick overview:

- Denial is the first stage, in which someone is unaware of difference, unaware of social hierarchies. It doesn’t last long in a highly racialized society like ours.

- Polarization is the most likely response when one becomes aware of difference: believing that those who are different are inferior. This is the stage we often think of when we think of racism—prejudice, stereotyping, individual discrimination, etc.

- Minimization frequently is the stage people move into when they want to move beyond polarization. If the only response to difference that you can envision is bigotry, then perhaps it’s best not to acknowledge that difference exists. When we talk about people being color-blind, minimization is what we mean. It’s important to note that IDI theorists consider minimization an ethnocentric stage. After all, you’re only pretending not to see difference, and you’re pretending not to see it from your own cultural perspective.

- Acceptance of difference is where we move when we become aware that minimization doesn’t work very well. We can see difference, we can accept difference, and we can appreciate it.

- Adaptation builds on acceptance once we have developed the behavioral skills to engage well with difference. We can act on the values of acceptance and navigate our way through cultural contexts different from our own.

I like this model. It explains a lot, and it helps people stuck in one stage see possibilities they haven’t considered before. It’s biggest limitation, I think, it that it is focused on the “horizontal dimension” of race, that of culture. In order to move toward antiracism, you have to understand the “vertical dimension,” too. You need to add equity literacy to your cultural literacy and account for both dimensions. That’s hard for people in dominant groups. Equity literacy in the U.S. requires White people to see all the ways in which being White makes life easier. It requires White people to recognize their participation in a society that prioritizes them over others. There is a lot of natural resistance to acknowledging those truths.

Embracing antiracism can be so difficult—and so transformational—that my Hope College colleague, Matt Jantzen (2020), describes it as a form of conversion. Following Christian Theologian James Cone, Jantzen writes that becoming antiracist requires that “those racialized as white might discover ways of being human that are not wholly captive to whiteness.” Like a religious conversion, an antiracism conversion may involve a moment of decision, but is followed by a long process of commitment, study, and growth. Furthermore, he writes, conversion to antiracism is “not an individual achievement. It must be nourished, encouraged, and held accountable by a community.”

To compare embracing antiracism to a religious conversion is to recognize that we live in a society so infused with racism that it takes deliberate, intentional effort to go against the cultural flow. Dr. King made the same point with a psychological rather than a spiritual metaphor—the idea that this is a society to which we should not adjust; rather, this is a society in which we should be maladjusted.

Psychologist Beverly Daniel Tatum (1997) has another helpful analogy. She likens racism to the moving sidewalks you see in airports, the conveyor belts that take you from one terminal to the next while you stand still. If you think of the sidewalk as the legacy of racism, active racists are the ones who walk on ahead, trying to move even faster than the sidewalk itself. Those who are neutral are just standing there—but the sidewalk is taking them along whether they want to go or not. If you don’t want to end up where the sidewalk is going, you have to turn around and walk the other way. You can try to be neutral—non-racist—but the sidewalk is still taking you in a racist direction.

Whatever your metaphor, to embrace antiracism is to think carefully about all kinds of decisions–where to live, where to work, where to worship, where to send your kids to school, where and how to spend your money, etc. More on all that in the section called Getting Personal under Our Options: Where We Go from Here.

The Bottom Line: This one goes to one of my heroes, the late Congressman John Lewis. Just before he died, he penned these final words to the American people:

Though I may not be here with you, I urge you to answer the highest calling of your heart and stand up for what you truly believe. In my life I have done all I can to demonstrate that the way of peace, the way of love and nonviolence is the more excellent way. Now it is your turn to let freedom ring.