If you are a member of a racialized minority group in this country, chances are that you began thinking about racial differences in social power long before now. If you are White, maybe not so much. Andrew Hacker (1992), Professor Emeritus of Political Science at Queens College in New York City, offers a compelling question to help us think about the issue. He asks White people to suppose that there is a secret office responsible for determining the race of every American. An official from this office contacts you one day to explain that a mistake was made when you were born. You’re supposed to be Black, not White, and the law requires that this oversight be corrected immediately. Tomorrow morning, you will wake up with chocolate brown skin and an Afro hairstyle. The official says, however, that he understands that this will be a big change, and the agency is willing to offer you some “reasonable recompense.” You are scheduled to live the rest of your life as a Black American. How much compensation (or reparation, perhaps?) would be fair?

How much, indeed, would White people want in exchange for being Black in America? Prof. Hacker has asked this question many times, and reports that a million dollars a year is a pretty standard response. Apparently, no one ever replied, “Oh, I don’t need any money. Racism is a thing of the past. The playing field is level, and I feel ready to pick up my life where it left off. No problem. Thanks anyway.” Perhaps the fantasy of waking up rich, as well as Black, plays some role in these responses. But people provide some pretty compelling reasons for wanting the money, most of which have to do with the prospect that life as a Black person will be more difficult because of limited access to valued resources like jobs and education and the likelihood that somewhere along the way, racial prejudice will hold them back. It’s easy to dismiss others’ concerns about fair treatment when it’s not happening to you or to people with whom you are close. You take it more seriously when confronted with the prospect of spending the rest of your life with significantly less access to social and economic resources than you currently have.

This is important–perhaps more important than you realize. As Ibram Kendi says, “Just as you can recognize an impoverished country by its widespread poverty, you can recognize a racist country by its widespread racial inequity.” Let’s see how some of those resources currently break down by race and ethnicity.

Income and Poverty

The best predictor of your income is your parents’ income. (Most of this research has been done on fathers and sons, but the principles presumably apply to parents and children generally.) Still, there is some movement up and down the economic ladder from one generation to the next. However, Collins and Wanamaker of the National Bureau of Economic Research report that, since Reconstruction, Black male mobility has lagged White male mobility, even for people from families with similar economic resources. Does class matter? Of course. But so does race. If poor Black social mobility were as high as poor White social mobility, racial disparities in income would be much smaller than they are today.

Are you a podcast person? If so, I recommend these six episodes from On the Media, a public radio show. They will provide a big-picture overview of poverty in the U.S.

But why is Black social mobility, especially poor Black social mobility, so difficult? Collins and Wanamaker attribute the persistence of the gap to the fact that while poor Black and poor White people have approximately the same amount of money, they do not have access to the same number of other resources. Poor Black people are more likely to live in neighborhoods of concentrated poverty, with poorer schools and less access to social networks that can provide opportunities to move up the ladder. When you add to that continued discrimination in both education and the job market (see, for example, Devah Pager’s research here), we begin to see why Black economic mobility has been relatively slow.

Economist Raj Chetty studies upward mobility and downward mobility in his research program called Opportunity Insights. He finds that race is a critical variable in both those measures—for men much more so than for women. The 30-minute video above will give you a pretty good overview of their basic findings, as will this written summary.

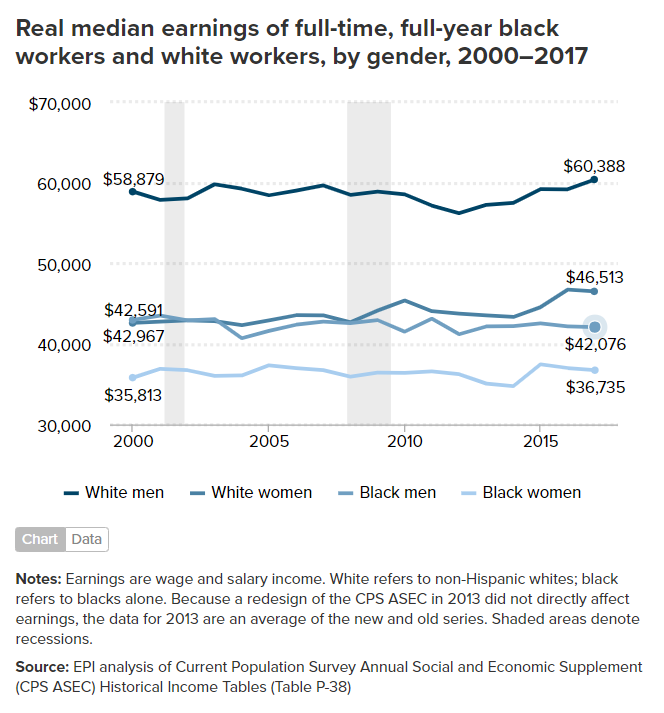

So what is the current income distribution in the U.S. by race and ethnicity? This chart, based on Census Bureau data (above) tracks median (50th percentile) income for the largest racial/ethnic groups from 1967 to 2018. As you can see the general trend has been a slow, gradual increase, but the disparities between one group and another have changed very little over the years. You see the same thing through most of the decades since World War II. (Unfortunately, a lot of information about ethnicity and income does not include Native Americans. As it turns out, median Native income tracks median Black income pretty closely.) Median income doesn’t tell the whole story, of course. The Pew Research Center reports that over the last twenty years, Black families with incomes below the Black median aren’t as far below as they used to be, which is a step in the right direction.

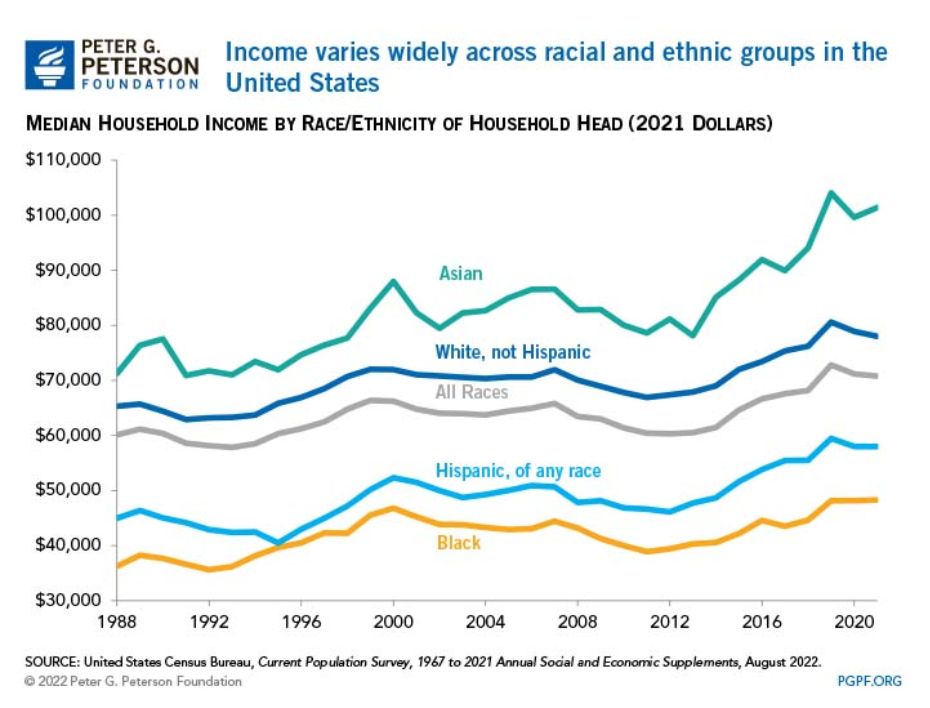

Race/ethnicity, of course, isn’t the only social identity that affects income. The intersection of race and gender tells a very important story, as you can see from this graph:

In addition to the average differences by race and gender, it’s important to note that although the economy grew significantly between 2000 and 2017 (in spite of the Great Recession), and in spite of the fact that productivity rose as well, median wages were essentially stagnant across that time. It’s one more sign that while our economy is growing, most of the time, only a few people at the top have benefitted. Click here to see equivalent data (in a table, not a chart) through 2021. Not much has changed. Go here to see an interactive graph that includes Hispanic and Asian workers, too. You can select the specific groups you want to see.

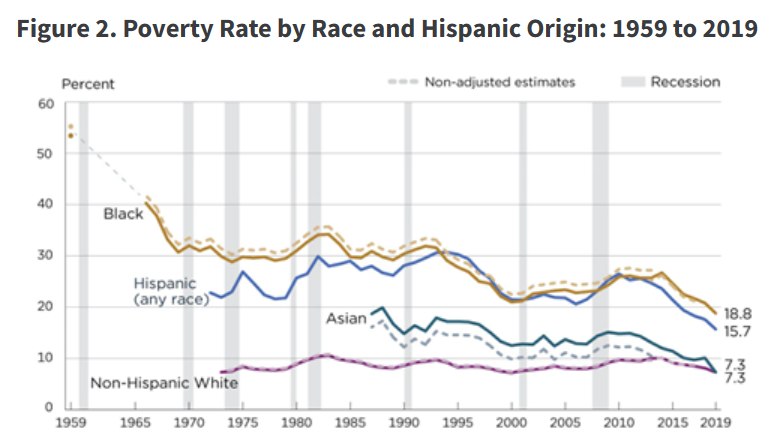

Lower average income means higher average poverty, of course. According to Census Bureau data reported by the Economic Policy Institute, the poverty rate for Black (19%) and Hispanic (16%) Americans is much higher than for White and Asian Americans (7%). The poverty rates for Black and Hispanic children are especially high (26% and 21%, respectively) relative to White children (8%). In truth, a more accurate term for “the poverty line” would be “the abject poverty line.” In most places around the country, you have to be at about twice the poverty level in order to pay for food, housing, transportation, and other essentials of daily living. And please don’t think that the federal minimum wage keeps people out of poverty. The poverty line for a family of four is about $26,000. A full-time worker would need to earn $13 an hour to make that much money in a year. The federal minimum wage is $7.25 and it hasn’t been raised one cent since 2009.

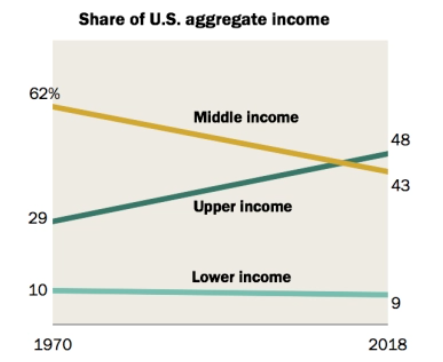

Just to reiterate: the big-picture context of income in the U.S. since the 1980s is that the well-to-do are making a lot more money, and at the expense of the middle class, in particular. The Pew Research Center summarizes it in this chart.

There is some good news. As I write this in 2023, the lowest-earning workers have been getting some good-sized raises in the last few years and have been catching up a bit. A number of states and cities have increased their own minimum wage, which has helped. And the labor shortage caused by the pandemic led to wage increases across the country, especially for those at the lower end of the scale. Time will tell whether this turns out to be a blip or a trend.

Wealth

Differences in wealth (your assets minus your debts—your net worth1) are even more striking than differences in income because wealth includes money and other assets inherited from previous generations. It therefore reflects the past even more than it reflects the present (Conley, 2003). Wealth-related assets include, but are not limited to, things that provide a rich, nurturing environment for children: safe neighborhoods, good schools, summer camps, music lessons, organized sports, vacations, strong social networks, etc. Wealth provides more than money and things; it also provides experiences, perspectives, and opportunities that make all the difference in the world.

Nearly two decades ago, Sociologists Melvin Oliver and Thomas Shapiro (2006), found that Black families’ average net worth is between 7% and 10% that of White families—not 10% lower, 10% as much. That has been true for decades, and it’s still true today. Furthermore, the gap has remained quite constant in percentage terms, meaning that as societal wealth grows, the actual dollar value of the discrepancy is increasing.

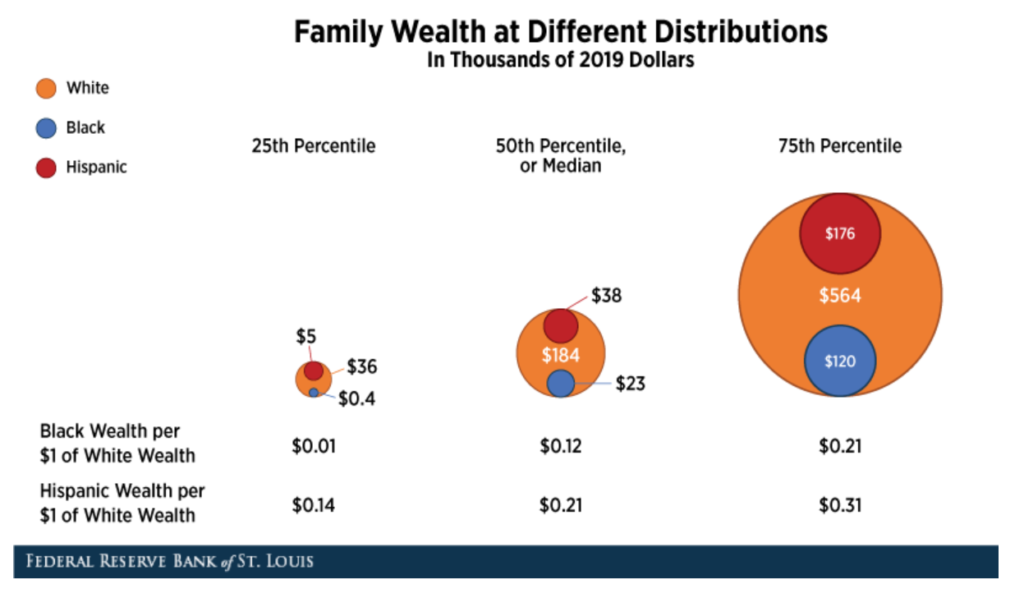

The Federal Reserve Board of St. Louis has an excellent summary of racial wealth gaps. They report that in 2019, the average White family (i.e., the 50th percentile) had $184,000 in family wealth, the average Black family had $23,000, and the average Hispanic family had $38,000. They offer this illustration that includes the 25th and 75th percentiles, too:

Jenna Ross, writing for VisualCapitalist.com (along with everyone else who studies these things), says that a big reason White people have more wealth is that they are more likely to own a home, and to have a home that increases in value over time. This is due, primarily, to an interconnected set of discriminatory policies and practices, past and present. The Demos Policy and Research Team notes that homeownership policy “shapes” the racial wealth gap, working in tandem with discrimination in banking and the real estate industry. Richard Rothstein, author of The Color of Law agrees, pointing out that everything about housing in the U.S. is designed to benefit White people at the expense of everyone else. He scoffs at the idea that segregation just happens, saying in testimony before congress that, “[t]his notion of de facto segregation is utter nonsense.” Segregation is at the heart of all kinds of housing policies, all designed to build wealth largely for White people.

There are other reasons for greater White wealth, too. White people also are more likely to own a car, have retirement accounts and a stock portfolio, and are more likely to own all or part of a family business. Perhaps most important of all, White people are far more likely to receive an inheritance (especially a large inheritance) when their parents die.

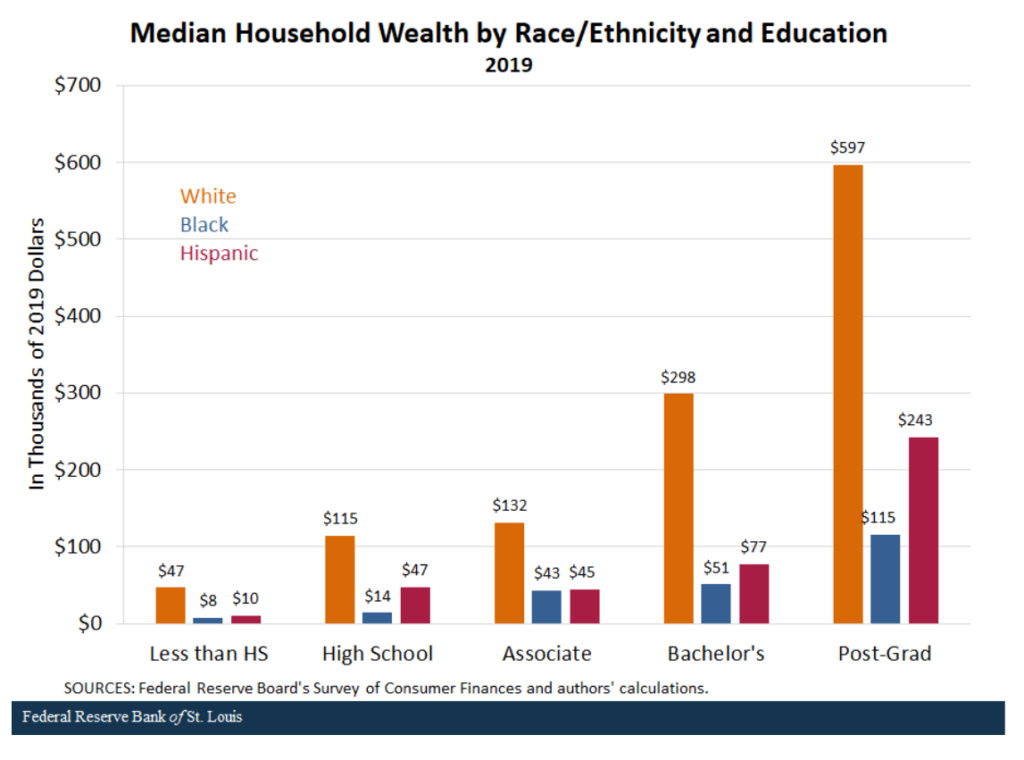

The answer must lie in education, right? That’s the golden ticket in this economy. Black and Latinx college grads do have more wealth than Black and Latinx people who didn’t go to college, but it doesn’t make as big a difference as you might think. Race differences in wealth are far greater than educational differences in wealth, as you can see in this chart:

White high school graduates have more wealth, on average, than do Black or Latino people with a college degree. In fact, Black post-grads have the same wealth as White high school grads. One reason is that students of color graduate with significantly more college debt than White students do. But much of it comes back, again, to intergenerational transfers of money, homes, and other assets.

As with income, gender matters with wealth, too. A study done by the Samuel Dubois Cook Center at Duke University concludes with this assessment:

“The data presented here shows us that neither marriage, a college education nor a lifetime of work provides the answer for equalizing opportunity between black and white women. Black and white women are positioned differently from one another largely because white women benefit more from wealth being passed down from their families. Intergenerational transfers like financing a college education, providing help with the down payment on a house and other gifts to seed asset accumulation are central sources of wealth building.”

These are just some of the reasons that if current policies stay in place, it will take Black Americans 228 years to accumulate as much wealth as White Americans have today. That’s almost as long as there has been a United States of America.

You may be wondering about whether White people are more financially responsible than Black people, and, if so, whether that explains the wealth gap. The answer? No. No. And No. It isn’t savings rates, personal responsibility, financial literacy, family structure, or any of the other “explanations” some people like to give. People from every racial/ethnic group work hard and do their best at approximately the same rates. White people, on average, simply have more opportunities for their hard work to pay off. Oliver and Shapiro (2006) call this the “sedimentation of racial inequality,” noting that “in central ways the cumulative effects of the past have seemingly cemented blacks to the bottom of society’s economic hierarchy.” Yes, slavery did end a long time ago, as many people love to point out, but discrimination continued on in different forms, and that’s still true today.

While Black Americans and other people of color suffer the brunt of these disparities, they affect us all. Wealth is not a zero-sum game for the economy. Money makes money at a macro as well as a micro level. If people of color had the same average wealth as White people, the entire economy would grow faster. It would be more than a trillion dollars larger at the end of the decade, and the GDP would be significantly larger, too. Fighting racism is the right thing to do, but it also is in our enlightened self-interest as a nation.

We could look at a hundred additional measures, and see racial disparities in education, health, healthcare, life expectancy, and nearly anything that is important in determining one’s quality of life. (The Atlantic has some interesting–and sobering–stats in an article entitled, “What if Black America Were a Country?”) Both race and economic class are important factors. Account for class differences, however, and race differences persist. Race is a separate, very important variable that has to be addressed on its own.

I’m hitting this pretty hard because very few White Americans know the facts about wealth inequality. Kraus et al. (2019) demonstrated that most White people assume that Black Americans have nearly as many assets as White people. That’s consistent, they point out, with the widespread belief among White people that we have made far more progress in the last sixty years than we really have. White Republicans are especially likely to report there is virtually no difference in Black and White wealth today. This “willful ignorance,” as Kraus et al. call it, is rooted largely in a belief that the world is a just place and that people get pretty much what they deserve in life.

Fortunately, Callaghan et al. (2021) found that simply giving people the facts about wealth inequality made them more likely to say—even 18 months later—that they believe the wealth gap is real. That’s why Katy Swalwell argues that, in addition to cultural literacy, we need to be teaching our kids about “equity literacy,” too.

While you’re here, take a look at these specific suggestions for promoting economic justice from The Othering & Belonging Institute at UC Berkeley. Just scroll down a bit along the outline in the left margin.

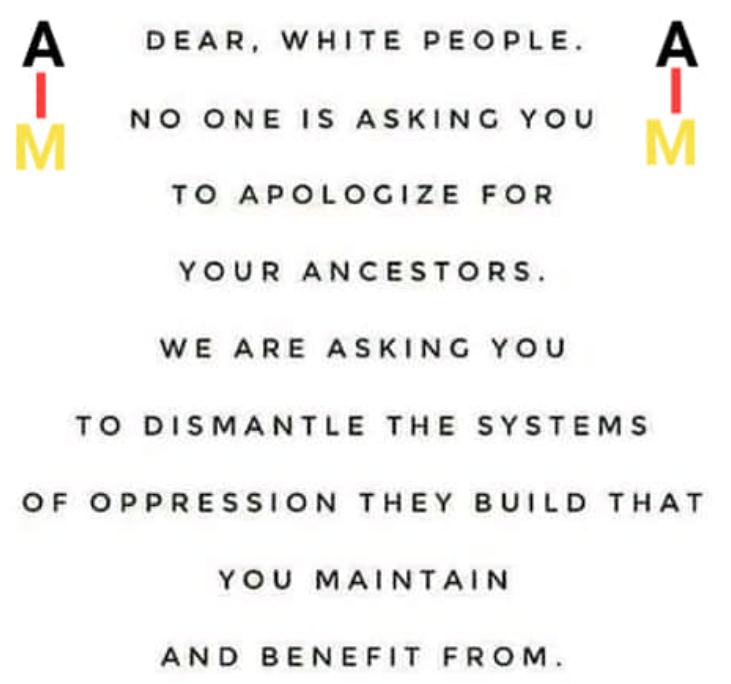

Reading all this may remind you of the manufactured outrage these days about “woke” people and “woke” policies and “woke corporations,” etc. People who don’t want us to know the truth about inequality can’t exactly stand up and say they love inequality and want to perpetuate it. So they have created a caricature of pro-equality people and initiatives and claim that those who are “woke” are disconnected from the way the world really is. In a sense, they’re right: to work for equality is to be in opposition to the status quo. Given that a reasonable discussion of the facts creates greater support for true equality, they have to distract us and scare us and appeal to our baser instincts, our tribalism. The fight against “wokeness” provides racists with cover for dismantling equity initiatives in business, education, and other sectors of society. It provides racists with cover for censoring teachers who want to teach the truth about the U.S. and its history. It’s all part of the age we live in, that of backlash to equal rights for everyone. (You can read more about that here and here and here.) Adam Serwer gives a good overview of the real purpose of being “anti-woke” and explains how people who howl at the moon about “wokeness” inadvertently reveal the racism in their own arguments.

As my Hope College colleague, Dr. Matt Jantzen, said in a video presentation on the history of racism and housing in Durham, North Carolina (at about 52:15 in the video),

“[T]he truth is that race has been written in concrete and asphalt, in dollars and cents, in our landscapes, in our neighborhoods, for decades if not centuries. So a real and effective response that is truth in action, not just word and speech, has to take those realities seriously.”

FOOTNOTE:

- In this context, ‘wealth’ refers to one’s net worth, and includes assets of any size; it does not necessarily connote a large amount of money, in the way we usually use the term.

The Bottom Line: As so many people have said, race matters. It shapes our lives, and the quality of our lives, in innumerable ways, offering advantages to some and disadvantages to others. Because racial justice is, indeed, the path to racial progress, there is no alternative but to address this fact head on.