I don’t want to write this.

Part of it is the difficulty of writing about race, politics, and religion in a way that is true, honest, and respectful. As a person of faith, I believe every human being is a child of God, beloved by God. That includes people who perpetuate racism. (I keep looking for an asterisk, an escape clause, or a list of exceptions in the Scriptures. No luck as of yet, but I’ll keep you posted.) At the same time, as a person of faith—more specifically as a Christian—I believe that Jesus cared quite particularly for those on the margins. He sought them out and brought them in. He gave them his time, his love, and eventually, his life. And he had no apparent difficulty “speaking truth to power.” When was the last time somebody called you a brood of vipers or a whitewashed tomb?

In the first two posts in this section on “The View from Above,” I wrote about the experiences and perspectives of that plurality of White Americans who rather vaguely want to do the right thing but don’t really know how and, for the most part, aren’t actively trying to figure it out. In this section, I write about that growing number of White Americans who are owning their racism, talking about it in public, sometimes with a veneer of respectability, but increasingly in horrid, shameful ways. They have always been part of the mix, but they now are emboldened. Some of them hold a great deal of political and economic power, and they do not intend to give it up. Others don’t hold much power themselves, but are deeply devoted to maintaining White Supremacy nonetheless. There are real concerns that the backlash to the civil rights movement has gotten so strong that we have entered an age of Jim Crow 2.0—and for good reason. (See, for example, Bentele and O’Brien, 2013.) We need to understand what’s going on and commit ourselves to stand against it. (As you read this, keep in mind that the number of White Americans who take racism seriously and want to do something about it is also rising. More on that in the next section.)

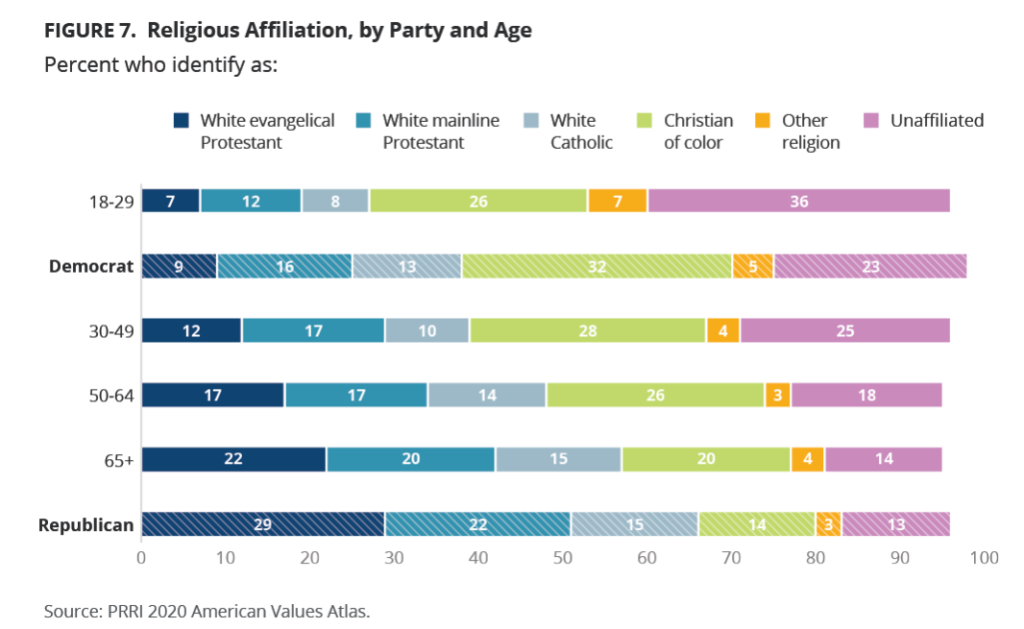

But first: we’re going to talk about race and politics and race and religion, keeping in mind that the two topics are intertwined, as you can see from this chart:

Race and Politics

For most of our history racism was big and loud and ugly. In the first few decades following the civil rights movement, more people were quiet about their racism, often keeping it “backstage.” Many still do, but an increasing number are bringing it right up front.

Historian Heather Cox Richardson puts all this in context for us. During the Great Depression, Franklin D. Roosevelt interrupted the political Gilded Age by putting the federal government mostly on the side of ordinary Americans (ordinary White Americans, that is). This followed decades of government favoritism for the wealthy and privileged. The 1954 Brown v. Board Supreme Court ruling, however, gave plutocrats the opening they needed: they began to connect, in the minds of many citizens, the policies of the New Deal with equal rights for people of color. They hoped that if working White people believed they had to choose between their economic interests and their racism, many would choose their racism. And, indeed, many did.

The Reagan Revolution was the culmination of that work. With a ready smile, Pres. Reagan cut taxes for the wealthy, reduced government oversight of the market, slashed the social safety net, and—not coincidentally—found ways to let racists know he was on their side.

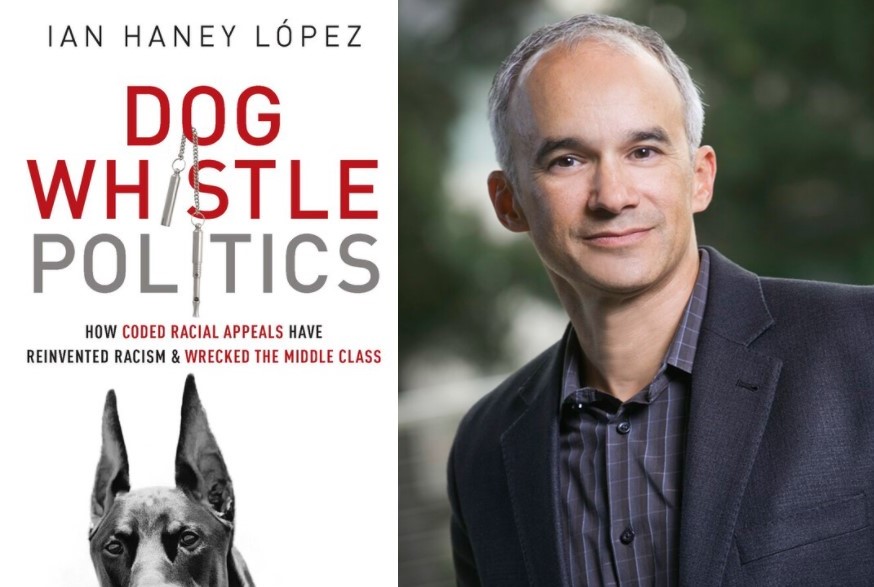

In Dog Whitle Politics (2014), Ian Haney López, who teaches law at the University of California, Berkeley, calls this “strategic racism.” Powerful people, especially politicians, use other people’s racism to advance their own interests. The specifics of the strategy can change over time (e.g., how openly racist to be), but the goal—to keep money and power in the hands of powerful White people—is constant. In the introduction to his book, López offers this overview:

So we need to be clear: the connection between race and the Republican Party is not accidental, vestigial, or comical, and it’s certainly not trivial. Instead, as we will see, over the last half-century conservatives have used racial pandering to win support from white voters for policies that principally favor the extremely wealthy and wreck the middle class. Running on racial appeals, the right has promised to protect supposedly embattled whites, when in reality it has largely harnessed govcrnment to the interests of the very affluent. Thc result is an economic crisis that has engulfed the nation . . .

Those who have wondered where in the world Donald Trump came from in 2016 need to understand that Goldwater, Nixon, and Reagan all made Trump possible. The big, angry backlash to Obama’s election made Trump inevitable. (What—you thought the Tea Party was about small government and fiscal responsibility?) And race runs right through the continuing assertions that Joe Biden’s election in 2020 was illegitimate. The same accusations were made about Southern elections during Reconstruction, and for the same reason: the belief that any election in which people of color help decide the outcome is illegitimate by definition. It’s the same belief that fuels the continuing efforts to limit the abilities of people of color to vote. If this is a White country, then White people deserve to choose the elected officials. That’s a big part of what “make America great again” means.

Even the use of the term “taxpayer” as opposed to “citizen” has had racist overtones. Historian Camille Walsh (2018) argues that from Reconstruction to the present day, race-baiting politicians have talked about “taxpayer rights” to signal that tax-paying citizens should have more rights than non-taxpaying citizens. That’s a pretty provocative assertion, made even more so by the fallacious insinuation that White people pay taxes and people of color do not. In the right context, spoken by the right politician, “taxpayers deserve” or “taxpayers need” is a signal to White voters that this candidate will prioritize them over people of color. Consider Mitt Romney’s distinction between “makers” and “takers” in the U.S. population. He suggested that 47% of Americans “are dependent upon government, who believe they are victims, who believe the government has a responsibility to take care of them, who believe they are entitled to health care, to food, to housing, to you name it.” It isn’t true. But if his remarks remind you of some White people’s beliefs about people of color, that’s no accident.

The single best predictor of White support for Donald Trump in the 2016 election? It wasn’t economic policy, abortion, guns, or foreign affairs. It was believing that Barack Obama is a Muslim.

Political Scientist Philip Klinkner in Vox

You may or may not appreciate this analysis of our current political divide, but here are just a few of the many, many facts about race and politics today:

In their 2020 annual report, the Public Religion Research Institute identified many differences in attitudes and beliefs between Republicans and Democrats—so many, in fact, they named their report Dueling Realities. Here are just some of those differences when it comes to race, ethnicity, and culture:

- 68% of Democrats believe that racial inequality is a critical issue to address; only 17% of Republicans agree.

- 77% of Republicans believe that Islam is at odds with U.S. values; only 26% of Democrats agree.

- 78% of Republicans (93% who trust Fox News more than other news sources) approved of Donald Trump’s handling of Black Lives Matter protests, versus 9% of Democrats.

- 79% of Republicans (and 90% of Republicans who trust Fox News), compared with only 17% of Democrats, believe that police killings of Black Americans are isolated incidents, and not part of a broader pattern.

- 49% of Republicans believe that the country is made better when Americans protest unfair treatment. However, only 24% of Republicans (10% of Fox News Republicans) agree that the protests of Black Americans make the country better. Among Democrats, there was no difference—71% for both “Americans” and for “Black Americans.”

- Republicans are more likely to say that there is significant discrimination against White people (57%) than against Black people (52%). For Democrats, 92% see discrimination against Black people and only 13% see discrimination against White people.

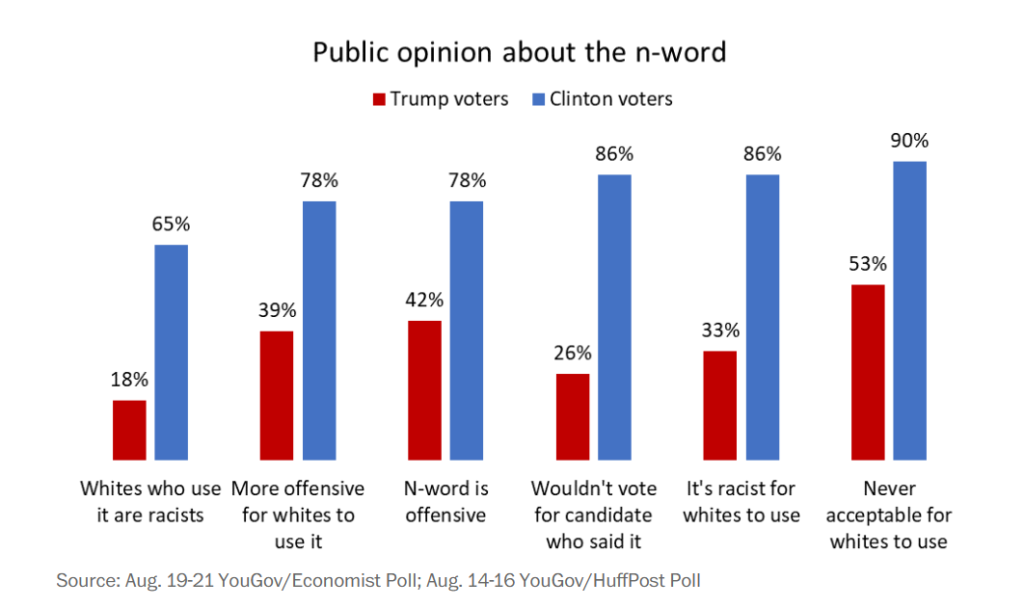

In a similar vein, the Pew Research Center reports that while 67% of Democrats see racism as a very big problem, on 18% of Republicans do. And while 72% of Republicans see immigration as a very big problem, only 29% of Democrats do. And just look at these differences in attitudes about using the n-word:

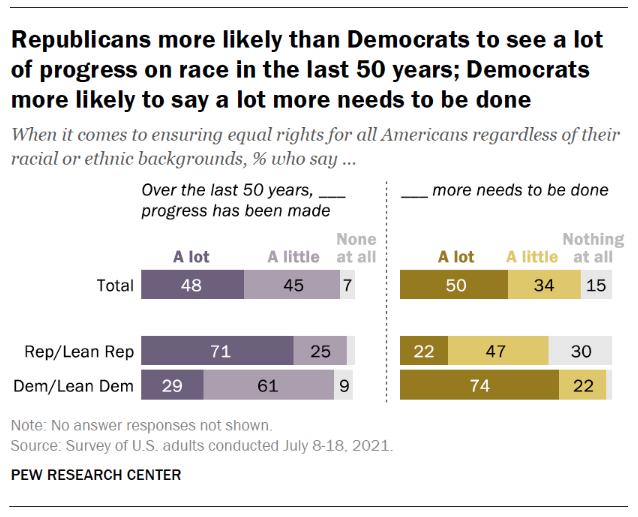

These large political differences in beliefs about racism lead inevitably to large differences in beliefs about the history of racism, and the extent to which it should be taught. It’s a two-step process. First, according to the Pew Research Center, Republicans are much more likely than Democrats to say that the U.S. has made a lot of progress combatting racism in the last fifty years.

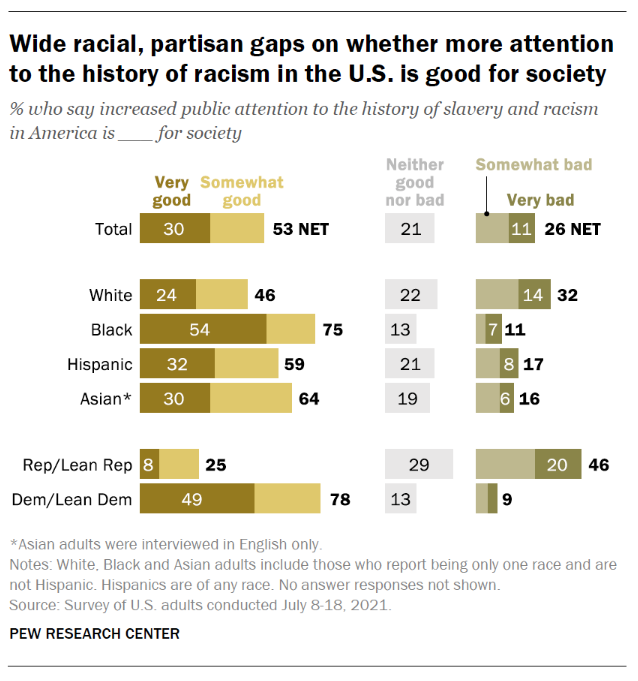

The second step follows from the first: Republicans are more likely than Democrats to oppose paying attention to the history of racism in this country, presumably to protect their belief that a great deal of progress has been made.

At the state level, Republican politicians have been moving pretty aggressively to limit teachers’ and professors’ ability to teach about racism, past or present. In the first three months of 2023, 21 bills were introduced in 13 states to limit university efforts to improve diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). Florida’s efforts to remove any mention of racism from any public school or university have gotten the most attention. In one case, the publisher of an elementary history textbook edited the story of Rosa Parks’ refusal to give up her seat on a bus in order to downplay the fact that she was fighting segregation. Some of these efforts are not merely Orwellian; they are absolutely surreal. The Florida State Board of Education is now requiring teachers to tell students that slavery was beneficial to Black people because it taught them skills. That’s what happens in an environment in which racists have all the latitude they need, all the authority they require to rewrite history in the service of White supremacy.

Those who propose banning any discussion of racism in classrooms often say they simply don’t want White children to be made to feel uncomfortable. Journalist Charles Blow doesn’t buy that. He argues that “whitewashing history” (pun intended, I assume) is not about protecting children; it’s about deceiving them.

As of this writing (2023), there are so many news stories about efforts to ban classroom discussions of racism that I simply can’t keep up. Differences between Republicans and Democrats on this issue are so large it’s difficult to see how they can come anywhere close to a common understanding of the basic facts of American history and life.

One thing to remember when comparing the views of Republicans and Democrats is that, according to the Pew Research Center, 81% of Republicans identify as White while only 59% of Democrats do. When comparing the attitudes of Republicans and Democrats, then, we are comparing a mostly White group of people with a more diverse group of people. However, there are consistent differences between White Democrats and White Republicans, too. For example, an April, 2021 opinion poll conducted by the Washington Post and ABC News found that 87% of White Democrats believe that ethnic minorities do not receive equal treatment in the criminal justice system; only 36% of White Republicans felt the same way.

“[W]e sort of have general agreement that government should help Americans, but what we disagree over is who gets to be American.”

—Political Scientist Lilliana Mason, interviewed by Ezra Klein.

Why does Donald Trump maintain such strong loyalty among most Republicans? Thomas B. Edsall offered many reasons and quoted many scholars in a column he wrote in the New York Times. Many Trump supporters believe that White dominance is under attack. The resulting fear and insecurity lead them to a sense of victimhood, and to believe they need to fight to regain the status they believe they have lost. Edsall quoted a political scientist at Temple University, Kevin Arceneaux, who studies the effects of psychological biases on political opinions:

The civil rights movement was about mobilizing an oppressed minority to fight for their rights, against the likelihood of state-sanctioned violence, while Trump’s appeals are about harnessing the power of the state to maintain white dominance. Trump’s appeals to discontented whites are reactionary in nature. They promise to go back to a time when whites were unquestionably at the top of the social hierarchy. These appeals are about keying into anger and fear, as opposed to hope, and they are about moving backward and not forward.

White fear and anger over diminished status is driven, in part, by Barack Obama’s election and the steady increase in the number of Americans of color. You can read more about both of those in the post But What’s Going On Right Now?

“As White power diminishes, White supremacy intensifies.”

—Political Consultant Paul Begala, quoted by Thomas B. Edsall

This is dangerous territory. Miller and Davis (2021) found that racism and anti-democratic values often go hand-in-hand:

“White Americans who would not want an immigrant/foreign worker, someone who speaks a different language, or someone from a different race as a neighbor are more likely to support strongman rule in the United States, rule of the U.S. government by the army, and are more likely to outright reject having a democracy for the United States.”

Naturally, White supremacist groups are encouraged and emboldened by the fact that racist ideas and attitudes are becoming more mainstream in political discourse. For example, White supremacy groups have taken to projecting racist imagery in Florida cities to help normalize racist ideologies.

And all over the nation, “active clubs” of White supremacists are training for physical violence, dressing in military garb, wearing masks, and threatening people of color and others on the margins. These groups are very loosely organized, but they do have an informal leader, a self-described fascist, White nationalist, and anti-Semite currently running from the law. In June 2023, many of the groups he inspired showed up at Pride events, especially in smaller cities, to harass and intimidate supporters of LGBT rights. In a nation where 79% of all adults (including two-thirds of Republicans) favor antidiscrimination laws that protect LGBT people, these groups know they can’t change enough minds to get a majority on their side. Instead, they use physical power to try to frighten people back into the closet.

If you are a Republican, no doubt this is difficult reading for you. I ask that you be open to the facts. And please know that I am not suggesting that you leave the party. I ask instead that you stay right where you are and make a difference from the inside. At the height of the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020, OJ Oleka wrote an essay entitled Why conservatives should be leading the way to end institutional racism. As a self-described conservative Black man, Dr. Oleka made the following argument:

Modern conservatism defends voluntary community, encourages strong families, praises earned wealth and demands honest labor. Racism oppresses. Conservatism liberates. Conservatives should be front and center, leading the way on how to end institutional racism in America.

Look at it like this: Democrats were the party of Jim Crow racism for over a century. 1948 was the first year they adopted a party platform in favor of civil rights. By 1964, only 18 years later, Lyndon Johnson, of all people, pushed the Civil Rights Act through a reluctant congress. Lord knows the Democrats continue to have their own problems with race, but they no longer organize their existence around the perpetuation of overt White Supremacy. There’s no reason the Republicans can’t make the same kind of change—but they first have to decide that it’s time, finally, to do the right thing.

Race and Religion

Still with me? I appreciate it.

In his compelling book, White Too Long: The Legacy of White Supremacy in American Christianity (2020), Robert P. Jones, the director of the Public Religion Research Institute, offers many examples of how White Christians are more likely to be racist than most other White Americans. Just a few examples (all taken from pages 161 – 172):

- White Christians are more likely than other Americans to assert that generations of slavery and discrimination make no difference in Black people’s ability to get ahead in life.

- White Christians are more likely to oppose immigration to the U.S., including legal immigration.

- White Christians were more likely to support Donald Trump’s ban on Muslims coming to the U.S., even for a visit, and more likely to support his vision of building a wall across the border with Mexico.

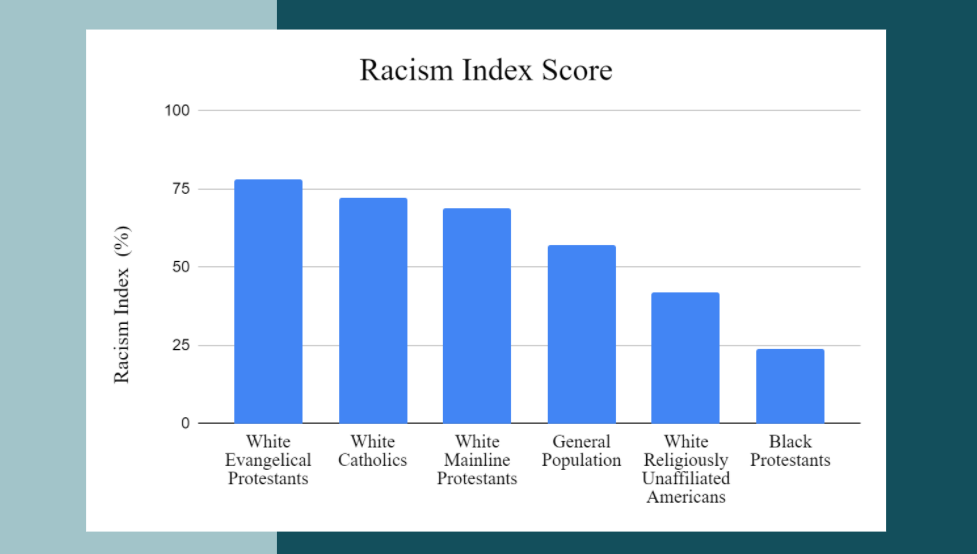

- White Christians score much higher on Jones’s Racism Index than any other group of Americans (see chart below).

As you can see, White evangelicals scored a bit higher than White Catholics or White mainline Protestants on the Racism Index, but the differences among these Christian groups are small. The differences between White Christians and other subsets of the population, however are sizeable. That is true for each of the issues in the list. White non-evangelical Christians who think that only evangelicals are racist are letting themselves and their churches off the hook way too easily.

This is just one small glimpse into the research on racism in the U.S. church. I could go on and on and on, but the point, sadly, would be the same: racism in this country is very strong among people whose faith teaches them—above all—to love both God and neighbor. Why would this be?

We have to begin with the role of the church in colonialism. The church was not a bystander; it was an active participant. When European Christians were looking for a justification for genocide and slavery, the church was there to help. The Doctrine of Discovery, laid out over the last half of the 15th Century, was the church’s blessing—a mandate, even—to conquer non-Europeans around the world and exploit their land and their labor. For centuries, the church has blessed Indian removal, slavery, Jim Crow, segregation, racial hierarchy, and racial inequity. There have been prophets along the way who preached the gospel Christ actually taught, but not enough. Mark Charles, a Navajo Christian pastor, explains it like this:

The Rev. Dr. E. Ross Kane of Virginia Theological Seminary argues that in aligning itself with conquest and colonialism, the church so thoroughly intertwined faith and White culture that it is difficult to know the difference anymore. Merging faith and culture is called syncretism. The Western church has been vigilant in calling out syncretism in colonized lands, trying to maintain the “purity” of the faith in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. But it paid no attention to the myriad ways that the racism of European culture infiltrated the church, from the local parish to the highest councils. Prof. Kane says

“White Christianity saw itself as the norm and as the primary bearer of divine revelation. It did not expect to discover something new through different cultures’ encounters with Christ. Rather, these cultures were expected to conform to largely White understandings of Christianity. The closer one came to White expressions of Christianity, the less likely one would be dubbed a syncretist. In this way, racism inhibited comprehension of divine revelation by narrowing its scope.”

Dr. George Kelsey (1965), a Christian theologian, believed that White Supremacy in Christians went beyond syncretism. He called it an idolatrous faith. He argued that racism was so inimical to Christianity that racist Christians should be considered polytheists:

“When the racist is also a Christian, which is often the case in America, he is frequently a polytheist. Historically, in polytheistic faiths, various gods have controlled various spheres of authority. Thus a Christian racist may think he lives under the requirements of the God of biblical faith in most areas of his life, but whenever matters of race impinge on his life, in every area so affected, the idol of race determines his attitude, decision, and action. . . . Polytheistic faith has been nowhere more evident than in that sizable group of Christiansn who take the position that racial traditions and practices in America are in no sense a religious matter. . . A probable explanation of this peculiar state of affairs is that modern Christianity and Christian civilization have domesticated racism so thoroughly that most Christians stand too close to assess it properly.”

Social scientists Meghan Garrity and Melissa Wilde (2023) illustrated one way that the U.S. church “domesticated racism so thoroughly.” They read everything American denominations wrote in 1935 about the rise of Hitler in Germany. In their official publications, only one mainstream Protestant denomination, liberal or conservative, was uniformly critical of Hitler’s policies. Some embraced him wholeheartedly. Others were more ambivalent. But only the Disciples of Christ took a clear stance against him. Jewish groups did, too, as did the Roman Catholic Church in the U.S., and the National Baptist Convention, a predominantly Black organization. For everyone else, the lure of racism was just too strong.

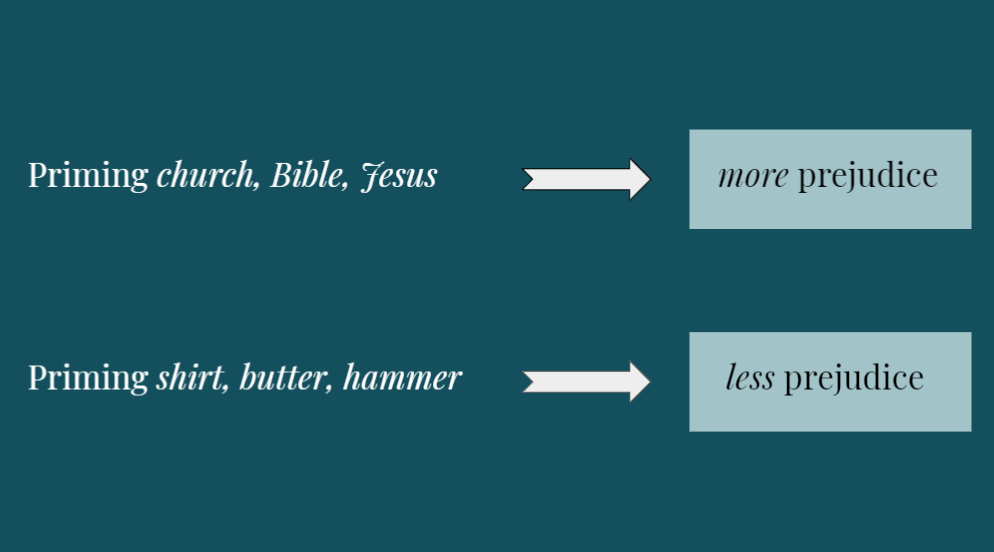

The historic links with racism continue to shape how we think about the Christian faith today. Baylor University social psychologists (Johnson, Rowatt, and LaBouff, 2010) found that White U.S. Christianity and racial prejudice are, indeed, deeply intertwined in our thinking. They primed research participants with Christian words like church, Bible, and Jesus—as opposed to neutral words like shirt, butter, and hammer— and learned that the Christian words led the participants to express more negative attitudes and feelings toward Black Americans—regardless of their own personal religious beliefs.

Christians and non-Christians alike implicitly associate the Christian faith with racial prejudice.

Sociologists Michael Emerson and Glenn Bracey have done a large, comprehensive study of the beliefs of practicing White Christians and come to the conclusion that about two-thirds of them are not even Christians by traditional standards. They adhere to biblical teachings and Christian principles when it’s convenient, but when it comes to loving their neighbor, they reject those teachings and worship the god of Whiteness instead. In the video below, Dr. Emerson offers an outline of their findings. His presentation begins at 19:25 and ends at 51:45. It is a provocative and informative half hour, and I strongly recommend it to you.

Friends, this is who we are—both to ourselves and to others—and it’s heresy. Gloria Purvis, who hosts a show on a Roman Catholic radio network, says it well:

“Racism makes a liar of God. It says not everyone is made in his image. What a horrible lie from the pit of hell.”

One more thing on this topic, and not just a post script. You could write a whole book on it. In fact, Andrew Whitehead and Samuel Perry already have, and I recommend it to you:

It is a data-driven analysis of Christian Nationalism, people for whom their Christian faith and their American patriotism have fused so completely that they see no discernable difference between the Kingdom of God and the U.S. of A. Measured in terms of agreement with just six questions, Christian Nationalism predicts all kinds of attitudes about race and racism, rooted in a very clear sense of the boundary that divides “us” from “them.” Christian Nationalists are more likely to believe that “true Americans” are White Christians, born in the U.S. with forebears from the U.S. Everyone else lives on the other side of the boundary, and therefore is highly suspect. Immigrants are seen as bad people who pollute the purity of the culture. U.S.-born minorities are believed to be lazy or criminal or both, people who deserve substandard housing, low-paying jobs, and inferior schools. It is absolutely telling that those who have fused God and country are the biggest bigots in the nation. Racism is intertwined in the history of both the U.S. government and the U. S. church. Put them together, and the result is pure White supremacy.

The federal government should declare the United States a Christian nation.

The federal government should advocate Christian values.

The federal government should enforce strict separation of church and state.

The federal government should allow the display of religious symbols in public spaces.

The success of the United States is part of God’s plan.

The federal government should allow prayer in public schools.

These are the six items Whitehead and Perry used to measure support for Christian Nationalism. If you agree with an item, you get a point toward your CN score, except for the third item on the list. If you disagree with that one, you get a point.

The Public Religion Research Institute has studied Christian Nationalism, too (using a slightly different set of survey items from Whitehead and Perry). They find that Christian Nationalism predicts a wide range of extreme positions, including higher levels of bigotry against Black people, immigrants, and Muslims; greater support for political violence; and greater likelihood of believing bizarre conspiracy theories like QAnon. You won’t be surprised to learn, then, that Christian Nationalism is an excellent predictor of support for Donald Trump.

Now please don’t conclude that all Christians in this country are Christian Nationalists. That is far from the truth. Christians who are low in Christian Nationalism have beliefs about race that are completely opposite from Christian Nationalists. (More on that in the next section.) And many Christian Nationalists aren’t especially Christian, as measured by things like church attendance and Bible reading. It isn’t the Christian faith itself that promotes xenophobia and racism; it is the heresy of White Supremacy that has found its way into the hearts and minds of many, but by no means all, people who profess Christian beliefs.

Peter Wehner, who worked for Ronald Reagan and both Presidents Bush, summarizes it in this way:

Countless people who profess to be Christians are having their moral sensibilities shaped more by Tucker Carlson’s nightly monologues than by Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount. Perhaps without quite knowing it, many of those who most loudly proclaim the “pre-eminence of Christ” have turned him into a means to an end, a cruel, ugly and unforgiving end.

Can I get an Amen?

The Bottom Line: Overt racism is alive and well, and quite visible, especially in recent years. One reason is politics: the Republican party has played on White racial resentment in order to win votes, a strategy that has worked pretty well for them since the 1960s. A second reason is U.S. Christianity, which has been part and parcel of U.S. racism since Europeans first landed in the Americas. The good news comes in the next post: antiracism has been on the rise lately, too, offering some hope in what has been a pretty difficult time.