Which came first—race or racism?

Two generations ago, Sociologist Oliver Cromwell Cox, a Trinidadian immigrant to the U.S., published a classic work, Caste, Class, and Race, in which he argued that the ideology of race as we understand it had its origins in European colonialism (Cox, 1948). It stuns me to know that, by some accounts, the first African slaves were brought to the Western Hemisphere in 1501, less than a decade after Columbus and his men arrived at Hispaniola (National Black Catholic Clergy Caucus, 2001).

How could such conquest be justified by people who saw themselves as good Christians? The answer lay in demeaning the conquered. If American Indians and their mestizo descendants were less human than Europeans, then the confiscation of their lands and their gold could be justified. If Africans were less human than Europeans, then the confiscation of their very bodies could be justified. Better yet, if Europeans could conclude that Africans were particula rly well-suited to slavery, then they could argue that they were acting in the best interests of the enslaved, in accordance with a divine plan for their earthly improvement and heavenly salvation. Lazy people needed the discipline of slavery. Rhythmic, athletic people could work long hours in the hot sun and not be bothered. Childish, violent people needed to be controlled, for their own good and the protection of others. The origins of contemporary stereotypes about Black Americans, then, can be found in the justification for the slave trade (Hudson, 2004).

rly well-suited to slavery, then they could argue that they were acting in the best interests of the enslaved, in accordance with a divine plan for their earthly improvement and heavenly salvation. Lazy people needed the discipline of slavery. Rhythmic, athletic people could work long hours in the hot sun and not be bothered. Childish, violent people needed to be controlled, for their own good and the protection of others. The origins of contemporary stereotypes about Black Americans, then, can be found in the justification for the slave trade (Hudson, 2004).

Here’s the logic

Historian George Fredrickson (2002) notes that “It is the dominant view among scholars who have studied conceptions of difference in the ancient world that no concept truly equivalent to that of “race” can be detected in the thought of the Greeks, Romans, and early Christians.” Why? Because they had no pretense of believing in human equality. They considered themselves superior culturally, educationally, or religiously, and needed no further justification for subordinating others. In Enlightenment Europe, however, and on into the years of the American and French revolutions, came the belief, however tentative, that all men (and they did mean men) are created equal. How, then, to justify conquest and enslavement? Not by redefining “equal,” but by redefining “men.” Fredrickson describes the process this way:

“If a culture holds a premise of spiritual and temporal inequality, if a hierarchy exists that is unquestioned even by its lower-ranking members, as in the Indian caste system before the modern era, there is no incentive to deny the full humanity of underlings in order to treat them as impure or unworthy. [However,] if equality is the norm . . . groups of people within the society who are so despised or disparaged . . . can be denied the prospect of equal status only if they allegedly possess some extraordinary deficiency that makes them less than fully human” [pages 11 – 12].

It’s a fairly simple syllogism, actually:

1. All men are created equal.

2. Some, however, obviously are not equal.

3. Therefore, they are not fully men.

Most of us assume that racism led to the conquest of American Natives and to the enslavement of Africans. Cox, Fredrickson, and many others argue just the opposite: that conquest and slavery led to racism because of the need to justify what was being done. The idea of race as a fundamental difference among people groups was buttressed over the centuries as Europeans and their descendants continued to rule over other parts of the world. “Race” became a distinctive, and especially powerful, means of organizing a world view necessary to justify the social, political, and economic order of colonialism.

“It is impossible for us to suppose these creatures to be men, because, allowing them to be men, a suspicion would follow that we ourselves are not Christians.”

— Enlightenment philosopher Baron de Montesquieu

Historian Jacqueline Jones (2013) writes that “the myth of race is, at its heart, about power relations,” a myth that “serves as a rationale for brutality.” She goes on to say:

“Perhaps the greatest perversity of the idea of race is how truly meaningless it is. Strikingly malleable in its contours, depending on the exigencies of the moment, race is a catchall term, its insidious reach metastasizing in response to any number of competitions—for political rights, scarce resources, control over cheap labor, group security.”

Understanding the history is important. So is understanding that using race to justify racism still happens today. In The Vertical Dimension of Race, in the section called The History We Inhabit, we will see that it is still true that, as Jacqueline Jones put it, race and racism are largely about unjust power relations that demand a rationale.

Sociologists Michael Emerson and Christian Smith, in their compelling book, Divided by Faith (2000), refer to the unequal distribution of resources in U.S. as the “racialization” of the society, meaning that one’s race is a significant determinant of one’s life opportunities. There are strong needs–psychological, sociological, economic, and political–for people with a disproportionate share of power and resources to justify their position. The easiest way to do that is to assert that the people with more deserve to have more, and the people with less deserve to have less. Racism, according to Emerson and Smith, follows directly from that justification. They define racism as an ever-changing ideology with a constant purpose: the justification and perpetuation of racialization. Discrimination persists and, therefore, prejudice persists because of our need to justify the racial status quo.

The role of the church

George D. Kelsey was a theologian who taught Dr. King at Morehouse College and encouraged him to attend seminary. He agreed that racism began as a justification for cruelties of many kinds. He went on to argue, however, that over time it took on a life of its own. He begins his remarkable book, Racism and the Christian Understanding of Man (1965), with these words:

“Racism is a faith. It is a form of idolatry. . . It arose as an ideological justification for the constellations of political and economic power which were expressed in colonialism and slavery. . . But gradually the idea of the superior race was heightened and deepened in meaning and value . . . The alleged superior race became and now persists as a center of value and an object of devotion.”

Understanding racism as faith does explain its enduring appeal, and its remarkable ability to persevere–across generations–in spite of so much evidence that it is a lie. It is more than a syllogistic conclusion; it is an article of faith, and millions of people organize the rest of their worldview around it.

But how did the church get involved? I’m sorry to say that it was part and parcel of colonialism from the very beginning.

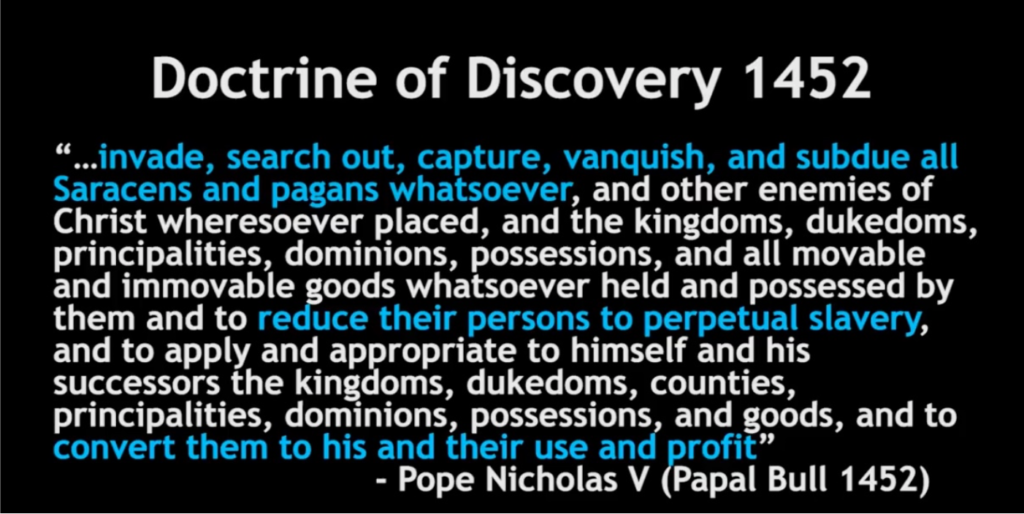

The Doctrine of Discovery was the church’s official policy of encouraging Europeans to invade other lands and exploit their wealth and their labor. In Unsettling Truths, Mark Charles and Soong-Chan Rah (2019) explain the doctrine and its effects. The first pronouncement (Dum Diversas, literally “while different”) was made in 1452 by Pope Nicholas V. It granted permission to Portugal to invade any non-Christian land, take ownership of both movable and immovable goods, and “reduce their persons to perpetual slavery.” In 1493, Pope Alexander VI gave similar permission to Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain. The church claimed (pretended?) that plunder and enslavement somehow were akin to preaching the gospel. The tithe colonizers were expected to pay to the church was motivating, no doubt. Theologian Willie Jennings (2010) reports that sometimes the tithe was paid in enslaved human beings, delivered up to the church, presumably to do the work of the kingdom. The question, of course, is which kingdom?

In a PBS documentary called Magellan’s Crossing (only available if you’re a PBS member), Historian Andrew Lambert describes colonizers’ perspective in this way:

“They looked at the world to control, to subjugate, and to exploit. That it’s the right and duty of Christian Europeans to dominate the world, at the expense of all other peoples, and everybody else they meet must convert to their faiths, follow their rules, obey their orders.”

The Doctrine of Discovery was even endorsed by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1823. In their ruling in Johnson and Graham’s Lessee v. William McIntosh, the court declared that indigenous people in North America were merely “occupants,” and the federal government had the right to buy their land or simply seize it outright (Nichols, 2009).

Charles and Rah note that Protestant colonizers had a similar vision for their work, often comparing the European invasion of North America with the children of Israel entering the Promised Land and conquering Canaan after their deliverance from Egypt. It’s one thing to see yourselves as children of God; it’s another thing to believe you are the only children of God, that you have a divine mandate to conquer other peoples’ lands and murder the inhabitants. Historian Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz (2014) explains that the English experience subjugating the rest of Great Britain and Ireland led them to decide that God had ordained them to rule over “inferior” peoples. She says it like this:

“The institutions of colonialism and methods for relocation, deportation, and expropriation of land had already been practiced, if not perfected, by the end of the fifteenth century. The rise of the modern state in western Europe was based on the accumulation of wealth by means of exploiting human labor and displacing millions of subsistence producers from their lands. The armies that did this work benefited from technological innovations that allowed the development of more effective weapons of death and destruction. When these states expanded overseas to obtain even more resources, land, and labor, they were not starting anew. . . In the lead-up to the formation of the United States, Protestantism uniquely refined white supremacy as part of a politico-religious ideology.”

Both the Catholic and Protestant justifications for colonization married the Christian faith to a strong belief in European superiority. The result was White supremacy, deeply embedded in society and blessed by the White church, which, in every generation, has found ways to profit from the racism it helped create.

The idea that the United States is an “exceptional” country—chosen by God, beloved by God above all other nations—comes directly from this line of thought. The belief that White Americans have a special place in the heart of God and a divine right to rule over everyone else continues to shape U.S. society and politics right up to the present day, energizing and rationalizing racism in all its forms. This Christian Nationalism, as it’s called, has grown in recent years. Read more about it here or here or here. For a deeper dive, read Taking America Back for God by Andrew Whitehead and Samuel Perry (2022).

Why are so many Christians unaware of this history? Because being honest about it would undermine White Supremacist justifications for the continued marginalization of people of color. Pastors Duke Kwon and Gregory Thompson (2020) argue that even after someone’s land is stolen, their labor is stolen, after all their assets have been stripped away and they have been robbed of their power, one final act of theft is required: erasing the truth about the crime that has been committed.

But wouldn’t it be better just to move on?

This is a hard truth. A harsh history demands a harsh recounting. But an honest, clear-eyed understanding of our current situation requires us to be straightforward with ourselves and with each other about how things came to be as they are. Sometimes White people assume that telling the unvarnished history is an attempt to make them feel guilty, or to silence them, or to deny their right to their feelings and opinions. Consider the uproar in some quarters when the New York Times Magazine published Nikole Hannah-Jones‘s 1619 Project, which drew a direct line between slavery and other racist policies and practices in U.S. history and the racial inequities that mark–and mar–our own time. Adam Serwer, who writes for The Atlantic, says that explaining that racism is rooted in such practices and policies threatens those in power because it makes room for “the idea that America can indeed be redeemed, by rectifying racial imbalances created by government policy.” Arguments about history are rarely about the past; they are almost always about the present and the choices we face today. See more about that here.

This is a hard truth. A harsh history demands a harsh recounting. But an honest, clear-eyed understanding of our current situation requires us to be straightforward with ourselves and with each other about how things came to be as they are. Sometimes White people assume that telling the unvarnished history is an attempt to make them feel guilty, or to silence them, or to deny their right to their feelings and opinions. Consider the uproar in some quarters when the New York Times Magazine published Nikole Hannah-Jones‘s 1619 Project, which drew a direct line between slavery and other racist policies and practices in U.S. history and the racial inequities that mark–and mar–our own time. Adam Serwer, who writes for The Atlantic, says that explaining that racism is rooted in such practices and policies threatens those in power because it makes room for “the idea that America can indeed be redeemed, by rectifying racial imbalances created by government policy.” Arguments about history are rarely about the past; they are almost always about the present and the choices we face today. See more about that here.

In his excellent memoir, Blood Done Sign My Name, Historian Timothy B. Tyson (2004) asks, “Why dredge this stuff up? Why linger on the past, which we cannot change?” He goes on to answer his own question: Because “the past holds the future in its grip—even, and perhaps especially, when it remains unacknowledged.” (page 307).

Here’s one concrete example of Prof. Tyson’s point: Acharya, Blackwell, and Sen (2016) found that Southern counties that had a large number of enslaved people in 1860 are more likely to be politically conservative and have a higher level of anti-Black prejudice to this day. Even after using statistical controls for other possible explanations, the great-great-great grandchildren of slave-holders are more likely to be White supremacists 150 years later. My guess is that they wonder why Black people can’t “just get over it” when they are the ones perpetuating racism across the generations.

That’s why many people want to censor the teaching of history in schools and universities. They understand that the lies they tell today are rooted in the lies they tell about the past. They are terrified that if we know the full truth of our history that we won’t believe their myths about the ways White people gained a dominant position in the U.S., myths that justify practices and policies that continue to benefit White people at the expense of everybody else. The desire to hide our history has been with us for centuries, but it gained significant strength—‘exploded’ is the word that comes to mind—in the backlash to the racial justice protests of 2020. It started in 2021 (see here and here), kept going strong in 2022 (see here and here), and hasn’t slowed down yet (see here and here). You can read more about that fight here.

I much prefer the approach of Retired Naval Commander Theodore Johnson, who writes about race and racism in the U.S.: “I write about race because I care about America.” He goes on to say

“The nation’s trouble is not that it has a racist bone that simply needs removing but that it is disturbingly slow to recognize that racism is the sharp pain that helps us locate the fractures. I write about race because finding the fractures in our society and our democracy is a necessary step toward healing and strengthening, not destroying, the whole of the nation.”

An anonymous Latin American researcher attending a British conference on slavery and reparations said it well: “If you take pride in the past, then you have to take responsibility, too.”1

Colonialism and Specific Ethnic Groups—The Next Three Essays

The themes, relationships, and social structures established in colonial times continue to shape attitudes and actions today. That’s true for specific marginalized racial/ethnic groups, too. The broad outline of their histories is similar, but there are differences, too, differences that matter. The essays that follow are a (very!) brief overview of the experiences of three racial/ethnic groups in the Americas during European colonialism. Look for the ways in which our early history continues to shape contemporary society, along with the ways in which people sometimes came together to demand progress. Knowing what really happened in the past is the best way to prepare ourselves to put things right in the present.

I had intended to write a fourth essay, too, focusing on Latino Americans. After writing the first three essays, however, I realized that much of the information about Latinos was covered already. (Remember that Latinos, by definition of the U.S. government, at least, can be of any race.) I thought then about writing an essay with a broader overview about Latinos, but there are quite of few of those that have been written already. If you’d like to read more about Hispanic/Latino Americans, I recommend the following sources as a good place to begin:

- The Pew Research Center has collected a great deal of information on Hispanic Americans. You can find an overview of basic facts and quite a number of reports on various topics (note the categories at the top of this page–language, education, and income).

- Statista also has a lot of information and reports.

- The History Channel has some basic information on its website.

- The National Endowment for the Humanities has information on Hispanic and Latino Heritage and History in the United States. It’s intended for teachers, but it has a lot of good information for any interested reader.

- PBS has a six-episode series on Latino Americans, all available online, along with a lot of other supporting information.

FOOTNOTE:

- This essay is part of an impressive special series published by the British newspaper The Guardian that explores “how slavery changed the Guardian, Britain, and the world.”

The Bottom Line: Race didn’t lead to racism; racism (that is, exploitation of non-Europeans by European colonizers) led to the concept of race. The very idea of race is a racist assertion, a justification of White superiority. The justification continues to this day, and everything else flows from there.