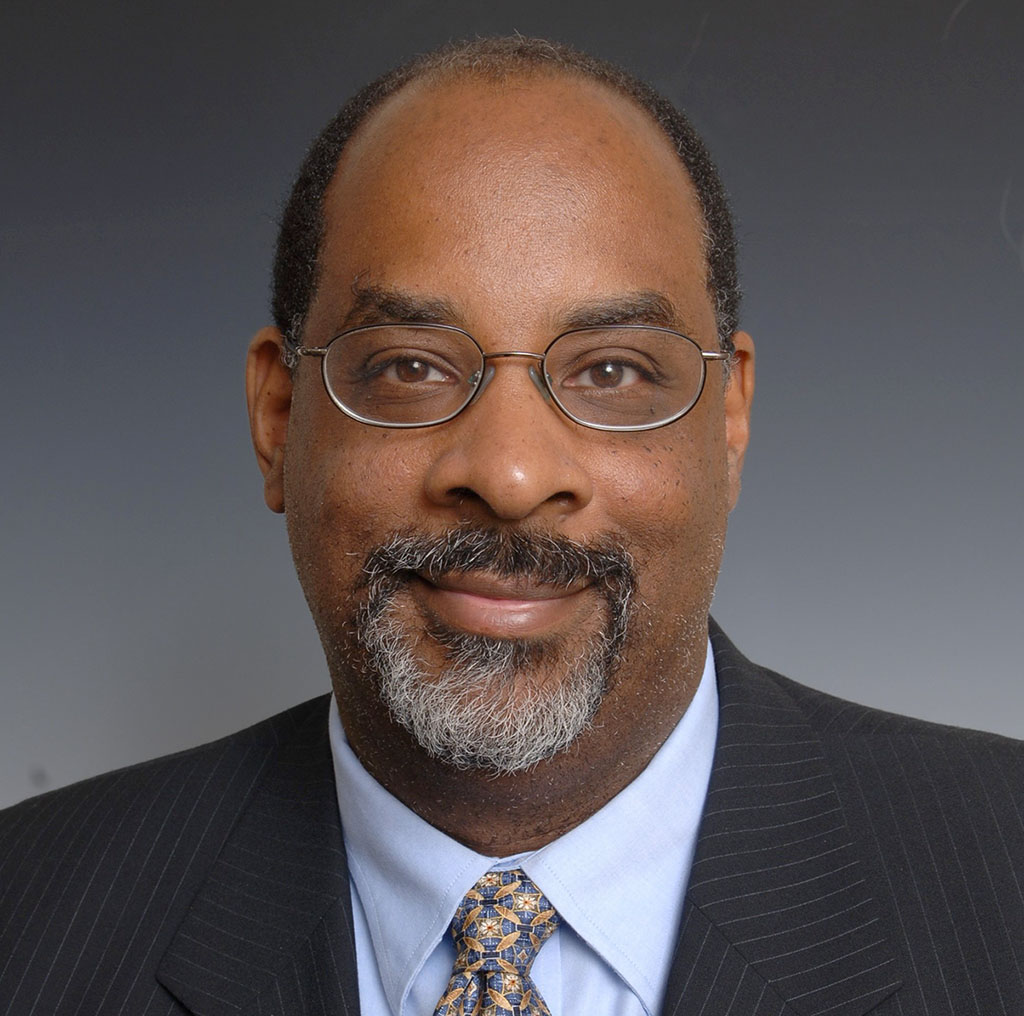

Social Psychologist James Jones (1997) says this about race:

“Race: This four-letter word has wreaked more havoc on people in the world than all the four-letter words banned by censors of the U.S. airwaves. Race divides human beings into categories that loom in our psyches. Racial differences create cavernous divides in our psychological understandings of who we are and who we should be. Race is a concept that is both very well understood (by biologists and geneticists) and poorly understood (by psychologists and the public at large). It means everything and it means nothing.”

What does race actually tell us about ourselves and others?

We think of races as collections of people who share certain important characteristics, characteristics that simultaneously mark them as similar to each other and as different from everyone else. However, on almost any dimension you can imagine, there is more variation within a “race” than there is between that “race” and another “race.” When we highlight skin color and a few facial features as a means to divide people into groups, we have to overlook a hundred ways in which people of different races are similar to each other, and another hundred ways in which people of the same race differ.

It makes about as much sense as the belief among some in Japan that one’s blood type determines one’s personality. Some people there even ask about blood type in job interviews. There are best-selling books and popular television shows on the subject, even match-making sites to help people find a mate with the right blood type. We find that absurd, and it is—but no more absurd than our obsession with race, and with far fewer consequences.

Most Americans still believe in the concept of race the way they believe in the law of gravity—they believe in it without even knowing what it is they believe in.

—Geneticist Joseph L. Graves, Jr.,

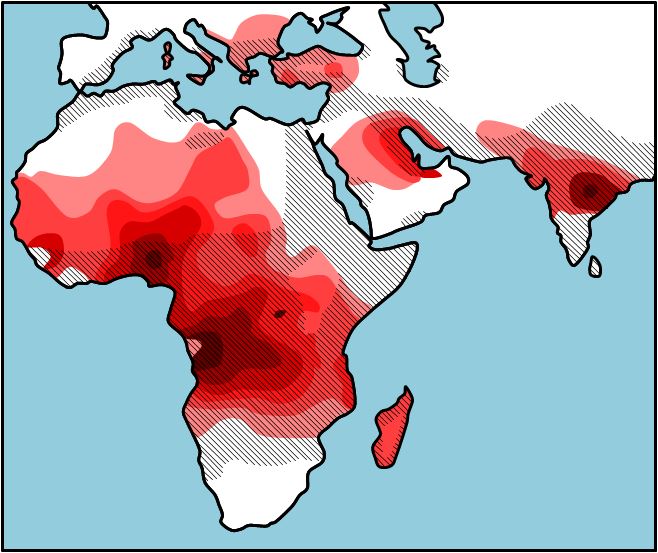

The Race Myth

Furthermore, although White Americans generally think of Black people as being a relatively homogeneous group,1 the truth is that there is more genetic variation among the assorted peoples of Africa than among the peoples of Europe and Asia combined. That’s because homo sapiens began in Africa. As people dispersed throughout the continent, genetic variation increased as a result of environmental differences, mutations, and intra-marriage within sub-populations. Some Africans left the continent to live, first, in the Middle East and, later, throughout Asia and Europe. But the people who left were not representative of the African population as a whole. They were a sub-set of Africans, presumably those from the northeast of the continent, closest to the route to Eurasia. The genetic variation among Asians and Europeans, therefore, reflects just a sub-set of the genetic variation in the whole of the African continent. And the genetic variability among Asians and Europeans is relatively similar, because they share common ancestors from just one part of Africa.2

Anthropologist Alan Goodman puts it like this: “On average, two individuals in Africa are more genetically dissimilar from each other than either of them is from an individual in Europe or Asia.” He says that geography matters in genetics, but that isn’t the same thing as race.

For example, a genetic predisposition for getting Sickle Cell disease is geographically based. Many Americans think of Sickle Cell as a disease Black people get, but that’s only partially true. Many Black Americans do get Sickle Cell, especially if they have ancestry from West-Central Africa. Black people from other parts of the continent have a much lower risk. Furthermore, people with ancestry from parts of the Mediterranean, the Arabian Peninsula, and India, people we don’t classify as Black, are susceptible to Sickle Cell. These different parts of the globe are prone to Sickle Cell because they also are prone to malaria, and the Sickle Cell mutation helps protect them from that. Population biology is real; race biology is not.

Race is an ideology, not a biological fact, more like witchcraft than empirical science.

In the U.S., our custom of hypodescent is another source of greater genetic variability among people of color. Hypodescent means that mixed-race children are categorized more often as belonging to the same group as their lower-status parent. Therefore, many Latinos, American Indians, and African-Americans have White ancestors, sometimes quite a few.

A few years back, Henry Louis Gates, Chair of the Department of African-American Studies at Harvard University, developed a television program for PBS called African- American Lives. Gates tested his own DNA for the program and learned that he has far more European ancestors than his family ever knew, perhaps as high as 50%. What does it really mean to be Black, biologically at least, if your great-great-great grandparents were just as likely to come from Sweden as from Senegal?

The American Association of Biological Anthropologists issued a Statement on Race and Racism in 2019. It is brief, but it covers a lot of important issues. It is definitely worth your time and attention.

The “White Gene”

Researchers have discovered the genetic mutation that led to the rise of lighter-skinned people in Europe (Lamason, 2005), a change that proved adaptive in the gray skies of the northern hemisphere because light-colored skin allows the body to absorb enough sunlight to produce Vitamin D.3 It is a measure of our collective ignorance of this topic that one of the researchers, Keith Cheng, told the Washington Post that he and his colleagues were nervous about presenting their findings to the public for fear that people might take their results as evidence of some fundamental difference between light- and dark-skinned people. In fact, their research demonstrates just the opposite—that this particular mutation was caused by a change in just one “letter” of DNA code out of the 3.1 billion letters in the human genome—truly, literally, “skin deep.”4 There are far more important differences among human sub-populations in height, body shape, distribution of blood types, and numerous other genetic markers, but we don’t assign those differences anywhere near the importance we give to skin color.5

Jefferson Fish (1995)—remember his story about avocados in Brazil and the U.S.?— demonstrates another way that our views of race are contradicted by our genes. He cites cases of bi-racial couples (one Black, one White) who have had fraternal twins— siblings born at the same time but from different eggs. Depending on the particular sequence of genes the children received from each parent, they may look fairly similar— as similar as any two siblings—or they may look quite different. Fish has identified cases in which one twin has light-colored skin while the other twin is quite dark. They have the same parents and are reared in the same home at the same time, but they are treated quite differently by other people and sometimes have very different life experiences as a result.

Categorical Confusions

Truth is, we encounter difficulties with our racial typology all the time, but we seem not to notice. Census Bureau data highlight some of the incongruities. For example, according to the 2020 census, 50 million Americans (out of 330 million) selected “Some Other Race” to describe at least part of their heritage. That’s 15%. Forty-five million of that fifty million also checked ‘yes’ to the question about Hispanic ethnicity. But why do they say they have some other race? Isn’t being Hispanic their race? Not according to the Census Bureau. The Bureau says that being Hispanic is an ethnicity, not a race. Hispanics (or Latinos, which some people prefer) are anyone in the U.S. who have at least one forebear who came to the U.S. from a country with a culture influenced by Spain, including Mexico, Central America, South America, former Spanish colonies in the Caribbean, and Spain itself.6

That’s a pretty big area and it includes people of every racial group recognized by the census. There are indigenous people, of course, and people who look a lot like their European ancestors. A large number of Black people, too; far more enslaved Africans were brought to Latin America than the U.S.—fifteen times as many (Telles, 2014). And it includes Asians, some of whose families immigrated to Latin America relatively recently (the largest number from China and Japan, but from many other countries, too) and some who have been there a very long time.

What about people of Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) descent? In most industrialized nations, MENA individuals are not considered White. But they are in the U.S., following a Jim Crow-era court case that ruled that MENA individuals are “White by law” (Maghbouleh, Schachter, and Flores, 2022).7 Most Americans, including MENA Americans, don’t think of people from that part of the world as White. A push to make MENA a separate race in the 2020 census (led by MENA organizations) was denied by the Trump administration. A similar push for the 2030 census is underway, though it isn’t clear whether it would be listed as another race or as an ethnicity like Hispanic.

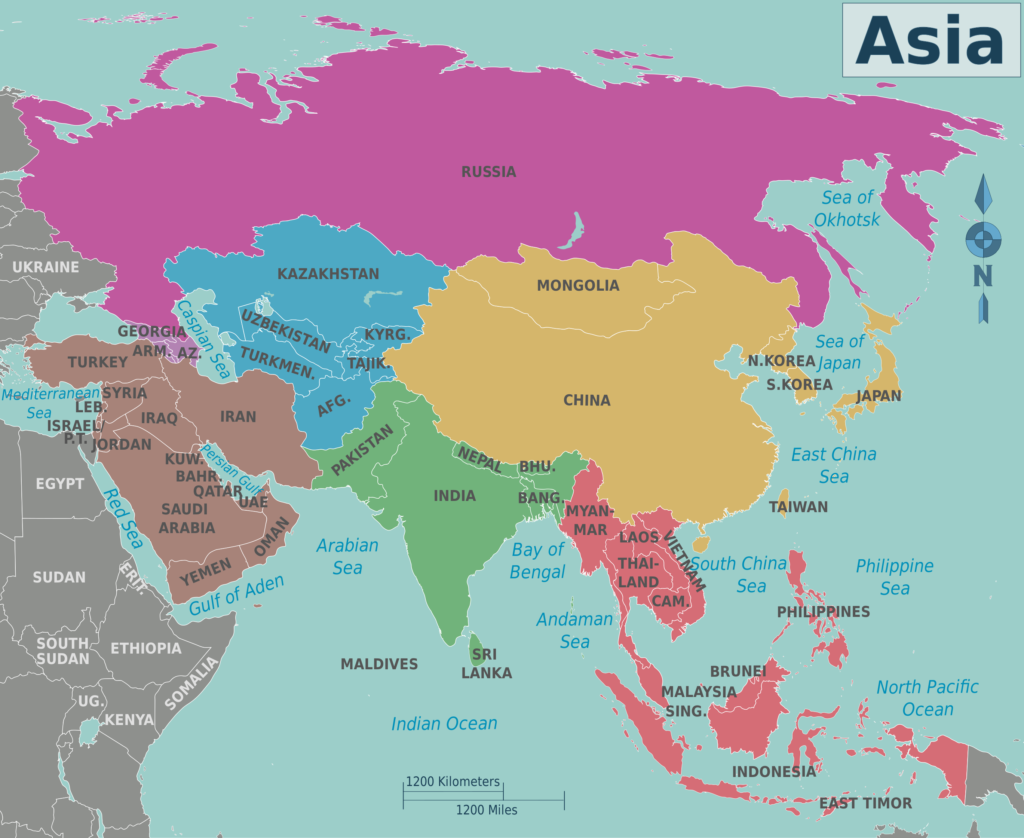

Another important question: What does it mean to be “Asian,” anyway? Asia is huge, covering 30% of all the land mass on earth. From Turkey to Iran to India, Cambodia, China, and Japan, Asians vary dramatically by culture, by skin color, by the shape of their eyes, and in countless other ways. They certainly have no pan-Asian concept of themselves (at least not until they end up here). The category is so broad as to be meaningless. Are Hawaiians and South Pacific Islanders a separate race? The federal government says so, but that’s a political accommodation, not an anthropological assessment. Still, when we speak of “Asians,” we seem to think that we mean something in particular, something different from “Whites” or “Blacks” or “Native Americans.” You wouldn’t believe the number of research studies done on the apparently simple question of how to categorize people by race and ethnicity in research studies (Saperstein, 2006). I’ve made my point: the whole idea of race as a biological reality is a hot mess that begins to fall apart with even the most basic scrutiny. Even so, it has such a hold on our thinking that we don’t notice those problems, and we can’t conceive of a different way of thinking about things.

- Have you noticed how some people refer to someone as being “from Africa,” failing to identify the nation to which they belong? It matters to most Americans whether someone is from England or from Italy—we can see differences between those countries. But many don’t care whether someone is from Ghana or Botswana, because they see Africans as all basically alike anyway.

- The details of this story are changing as anthropologists, geneticists, and others continue to collect new data. Thus far, however, the broad outline of this account is widely accepted by mainstream scientists. If you want a deeper dive, one good source is P. Bellwood (Ed.). (2013). The Global Prehistory of Human Migration. John Wiley & Sons. Another is this series of essays from the Social Science Research Council.

- More recent research suggests that there may be three genes that, together, produce light skin. The point nonetheless remains: skin color doesn’t mean much biologically.

- There is evidence that even Northern Europeans had dark skin as recently as 7,000 years ago. The development of agriculture may have accelerated the development of lighter skin, as a diet that includes a lot of grains has less Vitamin D than a hunter-gatherer diet (Olalde, Iñigo et al., 2014).

- “All of us are related, each of us is unique” is an English-language version of an exhibit on the meaning of race on permanent display in the Musée de l’Homme in Paris. You can see the exhibit online here.

- What about people in the U.S. with family from Brazil? Are they Hispanic? Not according to the Census Bureau, but some identify that way. Others, like a Brazilian-American acquaintance of mine, see themselves as Latino but not Hispanic. Others consider Brazil a category unto itself. A coding error in the 2020 census revealed some of the confusion surrounding this question.

- As you can imagine, there were lots of Jim Crow-era court cases asking the question of who qualified as being White, given that the extent to which the White/non-White line governed daily living and life opportunities, including citizenship. The result was a hodge-podge of contradictory rulings and moving targets.

The Bottom Line: Race means almost nothing in either biology or anthropology. Its power comes from history’s continuing influence, and from the fact that it still affects how we see ourselves and others. It is the ultimate self-fulfilling prophecy.

This article is look that very interested.

Thanks for sharing! Those are such good looking items.