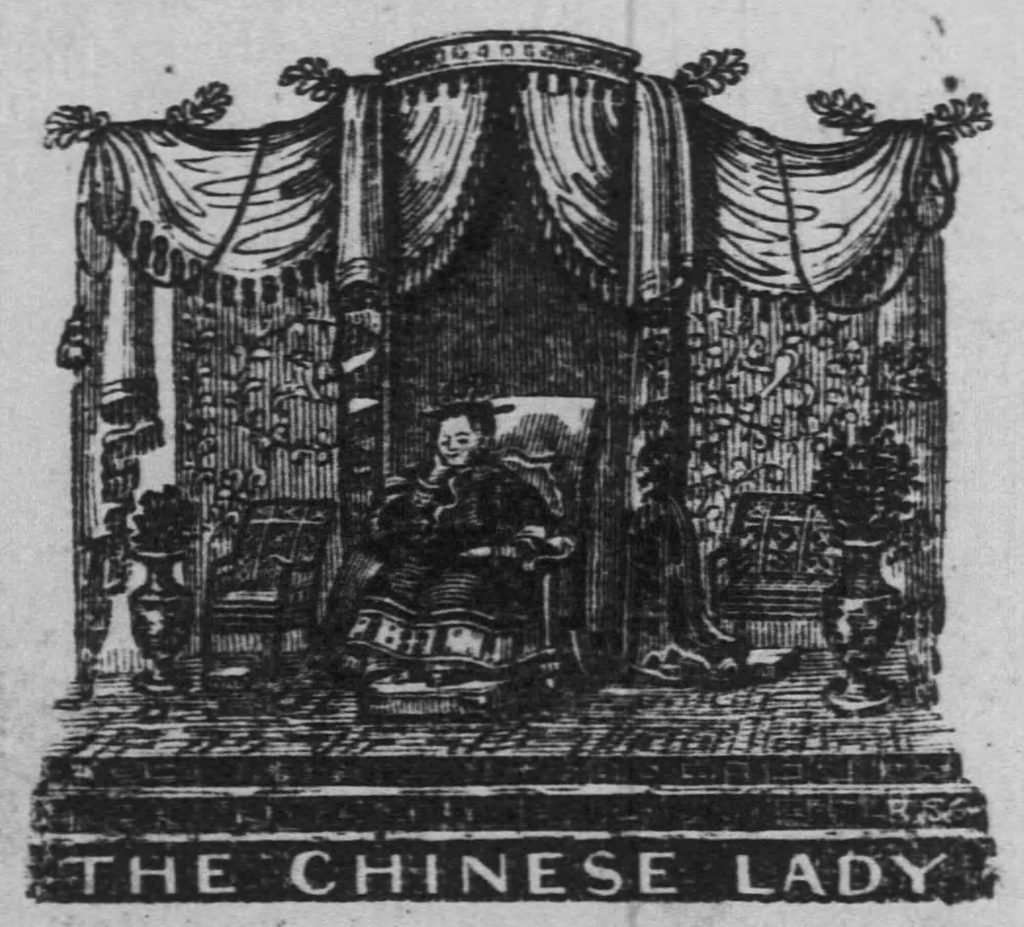

In 1834, two brothers and business partners, Francis and Nathaniel G. Carnes, brought tea, dishes, fabrics, artwork, fans, and other goods from China to the U.S. to sell to members of the growing upper-middle class. They also brought Afong Moy who, according to the available records, was the first Chinese woman in the United States. Ms. Moy turned out to be quite the attraction. The Carnes brothers charged upward of fifty cents admission for people who wanted to see a Chinese woman in person live on stage; through an interpreter, she presented examples of Chinese merchandise audience members could buy.

According to Nancy E. Davis (2019), Curator Emerita with the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History, Ms. Moy embodied a view of Asia as place of “exoticism, beauty, dignity, and revered history.” Just a few years later, in the midst of an economic depression, views of China had changed. Many people now thought of China as “backward, arbitrary, undemocratic, and sometimes cruel.”

Mixed Feelings and Vacillating Attitudes

It seems odd that attitudes could shift so much so quickly, but it’s just one example of the bipolar nature of U.S. attitudes about Asians and Asian-Americans. Consider the two most common stereotypes of East Asians: they represent a “yellow peril” intent on doing great harm and they are a “model minority” whose success proves that anyone can make it in America. What ties these apparently opposing views together? Journalist and Diplomat Curtis S. Chin says that they both are rooted in the belief that Asians can’t truly be American—that they are “interchangeable and perpetual foreigners.” BIAS theory (Cuddy, Fiske, and Glick, 2007) says that stereotypes are more complex than the unidimensional bad-to-good scale on which they usually are measured. To measure stereotypes accurately, you need to ask two questions instead of one. First: are your feelings about this group warm (positive) or cold (hostile)? Second: do you believe people in this group are generally competent or incompetent? On the whole, non-Asian Americans believe that Asians are competent, but their feelings about Asians shift dramatically depending on circumstances. Warm feelings about competent people lead to admiration; cold feelings about competent people lead to envy, resentment, and fear. These are the dynamics that underlie American ambivalence about Asian people.1

As I write this in 2022, many White Americans are scapegoating Asian Americans for problems that aren’t their fault. Hate crimes against Asian Americans rose dramatically during the coronavirus pandemic which the then-president called the “China virus,” the “China flu,” and the “Kung flu.” Asian Americans have been screamed at, slapped, hit, kicked, pushed, shot, and stabbed, sometimes fatally. Elderly people have been a frequent target, and some of the perpetrators have been adolescents. Anti-Asian violence cycles up and down through the nation’s history. I read a number of books, essays, and articles on Asian Americans and Asian American history as I prepared to write this essay. Those written five to fifteen years ago seem naively optimistic today as they talk about how successfully Asians have integrated into mainstream U.S. life and how well-accepted and admired they are by other Americans. As they did in Afong Moy’s day, prevailing attitudes have shifted from admiration (perceptions of competence plus warm feelings) to fear and envy (perceptions of competence plus cold feelings) in a very short period of time.

“To be Asian American is to straddle the tension of belonging and exclusion.”

–Raymond Chang, Asian American Christian Collaborative

The Orient as Other

It started early. Remember that Asia, not America, was the destination of early European explorers. However, the Ottoman Empire controlled the land route through the Middle East and the Portuguese controlled the water route across the Indian Ocean (Casale, 2006). The Spanish, British, French, and Dutch wanted their own access. Heading west across the Atlantic was the only option left for them. Why does this matter? Because while the Americas were new to Europeans, Asia was not. In the West, the East already had an image of mystery, wealth, danger, and intrigue.

Historian Erika Lee (2015) says that long before colonization, “Asia was consistently viewed as the West’s Other, an array of exotic lands and peoples that both fascinated and terrified Europeans.” These pan-Asian stereotypes continue to make it difficult for many non-Asian Americans to see Asian people for who they are, and to recognize the many differences among Asians in culture, language, religion, etc.

Asians in the Americas

Prof. Lee also notes that the Spanish were colonizing parts of Asia at the same time they were colonizing the Americas. Starting in 1565, the Spanish sailed “Manila galleons” filled with goods from Asia and the Middle East, departing from the Philippines and landing in Acapulco, Mexico. They built El Camino de Chine all the way to Veracruz on the Atlantic coast where they loaded the goods back on ships to sail across the Atlantic. Such an endeavor required an awful lot of labor, of course, bringing Asian sailors and other workers to the Western Hemisphere.

The British also brought both goods and people from Asia to North America—think of the ships full of tea floating in Boston Harbor in 1773. The U.S. began serious trade in Asia almost immediately after independence. Inevitably, Asian labor came along with Asian goods. Asian workers from various countries settled along the East Coast and in Southern fishing villages along the Gulf of Mexico. As the “triangle of trade” with West Africa diminished in the 1800s, more and more workers were brought from Asia to fill the gap, sometimes against their will. By the end of the 19th century, there were significant numbers of Asian laborers (often called “Coolies”) in Brazil, British Guiana, Costa Rica, Cuba, Jamaica, Mexico, Panama, Trinidad, and the United States. The pay was low and the work was hard. People in low-status positions often are demeaned—even dehumanized—by those who put them there, and attitudes toward Asians in America were generally quite negative during this time.

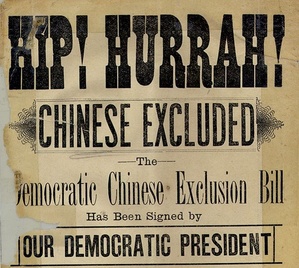

Organized Hate, Organized Violence

Anti-Chinese sentiments were widespread in 19th-century California, along with a number of anti-Chinese organizations. For example, the “Central anti-Coolie Club, No. 1., of Los Angeles Co.” was open to “[a]ny person sympathising [sic] with the white men and women in their opposition to the degrading and debasing influences of Chinese coolie labor.” Members had to pay fifty cents in dues, promise never to hire a Chinese worker, and boycott all businesses that did. Sometimes these hateful attitudes spilled over into violence. A lynch mob massacred nineteen Chinese immigrants in Los Angeles in 1871. In 1885, another White mob burned down the entire Chinese business district in Pasadena and forced those who lived there to leave town under threat of further violence. Both incidents were fueled by racist rantings in the local press, not unlike the false and inflammatory “border invasion” stories regularly broadcast by conservative media today. The Klan was active in California, too. They threatened to destroy the crops of any farmer who employed even one Chinese worker. They burned down a Methodist Church in San Jose because it had a Sunday School class for Chinese children. They threatened anyone who spoke out in favor of rights for Asians, all the while claiming that White people were being persecuted and were the real targets of discrimination (a claim also made by White supremacists today).

In his inaugural address in 1867, California Governor Henry Haight called Chinese workers a “curse” and went on to speak against the idea of any non-White Californian being given the vote. Claiming no “prejudice or ill will,” Haight said he was worried that equal rights for all would “introduce the antipathy of race” and “lead to strife and bloodshed.” (And we hear contemporary echoes once again. It isn’t those who deny equal rights who are causing tension, racists claim; it’s those who want equal rights who are stirring up trouble.)

University of Puget Sound students, supervised by History Professor Andrew Gomez, have put together an impressive website detailing anti-Chinese violence in Tacoma Washington, where the university is located. They also mapped other locations of anti-Chinese violence in the 19th century. Click on the link below to go to their site for more information about each incident.

Attitudes toward Asians in the Americas also reflect the ambivalence of people who have work that needs to be done but do not want the workers themselves. (Something else we see today, obviously.) Crops cannot be harvested remotely. Buildings (and transcontinental railroads) can’t be built from afar. So employers recruit laborers and bring them to the work site. But employees don’t disappear at the end of the workday. They require places to live, shop, play, and worship. However, many members of the dominant group don’t like the fact that workers are real people with real lives. In effect, we invite people to come and then punish them for being here.

Historian Ronald Takaki (1998) tells of agricultural booms in both Hawaii and California in the 19th century, requiring a large increase in workers. It was difficult work for very low pay. Most White people had better opportunities, so employers brought large numbers of people from Asia to do the work. Takaki notes that manufacturers saw the appeal of hiring Asians, too, because they could pay them lower wages. When Irish workers went on strike in San Francisco in 1870, demanding a raise from three dollars a day to four dollars a day, the factory fired them all and hired Chinese workers for one dollar a day. After the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, employers recruited workers from Japan and India (mostly Sikhs). The Philippines became a U.S. colony in 1898, which paved the way for Filipinos to come, too, especially as farm workers.2 Along with other people of color, Asian Americans were the ‘essential workers’ of that time. Even so, they faced bigotry and violence, and the government and the courts did everything possible to ensure they had no citizenship and no rights (Baldoz, 2017). There still weren’t enough workers, so in the early 20th century Mexicans were recruited to work the farms and orchards, which continues to this day.

Perpetual Foreigners

In 1790, the very first U.S. congress passed the Naturalization Act restricting citizenship to “any Alien being a free white person.” This was meant to exclude Native Americans and Black people, but courts subsequently ruled repeatedly that it applied to Asians, too. The inability to apply for citizenship (until 1952) meant that Asian Americans had a particularly precarious position in the U.S. even if they were born here. Many European immigrants faced difficulty and discrimination, but they had a path to citizenship, a right and an opportunity available literally to no one else. Sociologist Robert Park said it this way in 1914:

“[T]he chief obstacle to the assimilation of the Negro and the Oriental are not mental but physical traits. It is not because the Negro and the Japanese are so differently constituted that they do not assimilate. If they were given an opportunity the Japanese are quite as capable as the Italians, the Armenians, or the Slavs of acquiring our culture, and sharing our national ideals. The trouble is not with the Japanese mind but with the Japanese skin. The Jap is not the right color.

The fact that the Japanese bears in his features a distinctive racial hallmark, that he wears, so to speak, a racial uniform, classifies him. He cannot become a mere individual, indistinguishable in the cosmopolitan mass of the population, as is true, for example, of the Irish and, to a lesser extent, of some of the other immigrant races. The Japanese, like the Negro, is condemned to remain among us an abstraction, a symbol, and a symbol not merely of his own race, but of the Orient and of that vague, ill- defined menace we sometimes refer to as the “yellow peril.” This not only determines, to a very large extent, the attitude of the white world toward the yellow man, but it determines the attitude of the yellow man to the white. It puts between the races the invisible but very real gulf of self-consciousness.”3

A contemporary sociologist, Philip Q. Yang (2011), put it more succinctly: “[T]he experiences of prejudice, discrimination, and hostility have constantly reminded [Asian Americans] that their ethnic identity is real rather than symbolic, because they are treated differently.”

Fighting Back

We need to understand the breadth and the depth of racism directed against Asian Americans, across the centuries and on into the current moment. But we need to understand, as well, the many ways in which Asian Americans fought back, actively demanding—and sometimes receiving—their rights. When pushed out of their homes and neighborhoods, people relocated and started anew. When ignored by their elected officials, they protested, organized, and lobbied. When vilified by ignorant bigots, they held their heads up high and proved the haters wrong. Just a few examples:

- Chinese American railroad workers organized the largest labor strike of the mid-19th century, demanding equal pay (White workers were paid more for doing the very same job) and better working conditions.

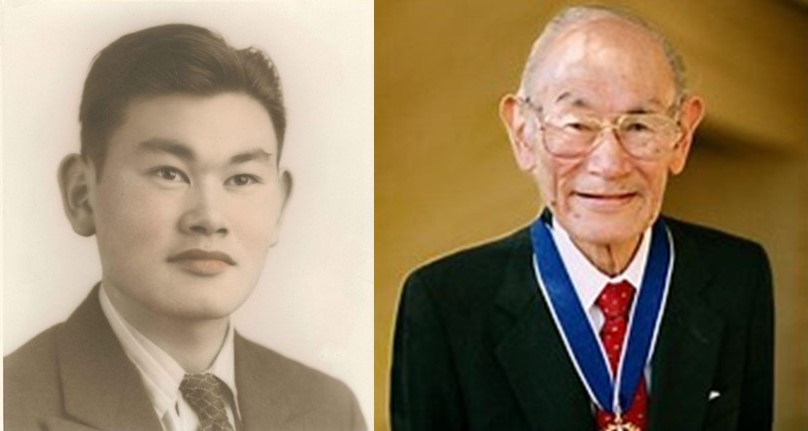

- There are many individual Asian Americans who have stood up for their rights, too. When Japanese Americans were sent to internment camps during World War II, Fred Korematsu sued the federal government to court to keep his freedom. He didn’t win, but he fought the good fight, and the Fred Korematsu Institute continues his work today. In 1998, he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

- In 1968, the Asian American Political Alliance at UC Berkeley and San Francisco State College joined with other student groups to form the Third World Liberation Front. Among other things, they were among the first to use the term Asian American and to contemplate the idea of a pan-Asian identity in the U.S. They also pushed for the creation of ethnic studies courses that would teach the history and culture of marginalized racial/ethnic groups. It was an important step in creating the serious academic study of Asian Americans and other minority groups. (Ethnic studies courses are now widespread in colleges and universities—but under renewed attack from those who want to keep our full national history from being taught.)

- There are numerous civil rights organizations dedicated to promoting the well-being of various Asian groups in the United States. One of the oldest is the Chinese American Citizens Alliance, chartered in 1915. The Japanese American Citizens League was founded in 1929, and many more such groups followed. I especially appreciate the fact that many of these organizations speak up for the rights of all Americans, not just those of Asian descent. For example, the Japanese American Citizens League advocated for the rights of Arab Americans in the aftermath of the 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center and the pentagon. At the time, some people were seriously advocating that the U.S. create internment camps for Arab Americans, following the model of Japanese internment camps in the 1940s. The JACL spoke out forcefully against the idea, holding us to our national ideals even though we were under attack. Another example: The Asian American Christian Collaborative has spoken out against anti-Semitism, in favor of Black Lives Matter, and decried the growing levels of violence against many different marginalized groups. Check out the many fine articles in their journal, Reclaim Magazine.

Historian Lon Kurashige (2016) reminds us that while Asian Americans historically were excluded from citizenship, from opportunity, even from the country itself, not everyone agreed with those decisions. Non-Asian allies spoke up and made a difference.

“Exclusion was not a rout; it was a debate. There were always two sides to the question. Even during the height of anti-Asian policies, when exclusionists won a series of victories, the organized and well-funded opposition included some of the most powerful leaders in fields of American politics, business, religion, academia, and culture. Exclusionists remained watchful and wary of their respected opponents; they never underestimated them.”

Here is one compelling example: The Bainbridge Island (Washington) Japanese Exclusion Memorial honors the Japanese American residents who were sent to internment camps during the second world war, and also tells the story of the many non-Japanese residents who fought their deportation and kept their farms and properties intact so that they could return after the war ended. This made all the difference: many people who were interned returned home to discover that their homes, businesses, and farms had been confiscated.

That’s important for us to keep in mind today. Working for the full rights and full inclusion of everyone is both principled and practical. It’s the right thing to do and it makes a difference.

Our Current Context

Asians have been in the Americas almost as long as Europeans. For the most part, they came to do difficult, sometimes dangerous work that most other people didn’t want to do. They faced a great deal of prejudice and, without the possibility of becoming citizens (until 1952), their position in this country was tenuous, at best. The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 opened up opportunities in the U.S. to people from around the world, including many from Asia. It also gave priority to applicants with advance degrees and technology skills (Dhingra and Rodriguez, 2021), meaning that many Asian (and other) immigrants since 1965 represent a highly educated slice of their home countries. As a result, average Asian-American incomes and educational attainment are impressive.4 Even so, “Model minority” stereotypes5 and “yellow peril” warnings comingle in popular consciousness, as evidenced by continuing anti-Asian bigotry and violence. Erika Lee says that Asian American inclusion continues to be “fragile,” as it has been throughout our history.

“To be Asian American in the twenty-first century is an exercise in coming to terms with a contradiction: benefiting from new positions of power and privilege while still being victims of hate crimes and microaggressions that dismiss Asian American issues and treat Asian Americans as outsiders in their own country.”

—Erika Lee, The Making of Asian America

FOOTNOTES:

- Psychologists Linda Zou and Sapna Cheryan (2017) have a different two-factor model of stereotypes: inferiority/superiority and foreignness/Americanness. They asked people from various racial/ethnic groups to describe their experiences with prejudice. Asian Americans’ experiences mostly fell into the category of superior and foreign.

- Filipinos continued to do farm work for decades. They were right at the heart of the farmworker movement in California, organizing with Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta.

- Note that in 1914, even a revered scholar such as Dr. Park, writing in a respected academic journal, used “Jap” for “Japanese,” a term widely recognized as an ethnic slur. Note, too, his use of “the Orient” and “Oriental.” Perhaps you’ve wondered why many people prefer the term “Asian” to “Oriental.” It’s because of that old stereotype Prof. Lee mentioned, that “the Orient” conjures up a mysterious land with “inscrutable,” treacherous people.

- Note I said average income and education. Asian Americans have some of the highest incomes in the country, but also some of the lowest. Many people who trace their lineage back to Southeast Asia came as refugees, some of whom have lower-than-average incomes. As a result, Asian Americans, as a group, have both high incomes and high poverty rates. For more information, see here and here.

- Keep in mind that the term model minority is not entirely positive. For one thing, sometimes people use it to suggest that other people of color have no excuse for not matching Asian standards of success, that racism does not hold anyone back. In addition, it can have patronizing overtones: You’re doing very well, so don’t push too hard and don’t rock the boat. For more information, see Wu (2017) and Dhingra and Rodriguez (2021).