Racial Progress

A lot has happened since my son—now a father himself—brought home that Black History Month Story. The number of White Americans who believe The Story has declined since then. Some rejected The Story in order to embrace an open, public, and politicized racial resentment (Abramowitz and McCoy, 2019). Others rejected The Story because they came to believe that racism is real and on-going. Collectively, we’re moving in opposite directions at the same time. Are things getting better? Yes. Are things getting worse? Yes. So how did we end up here? Well, a lot’s been going on . . .

How some White people respond to demographic change

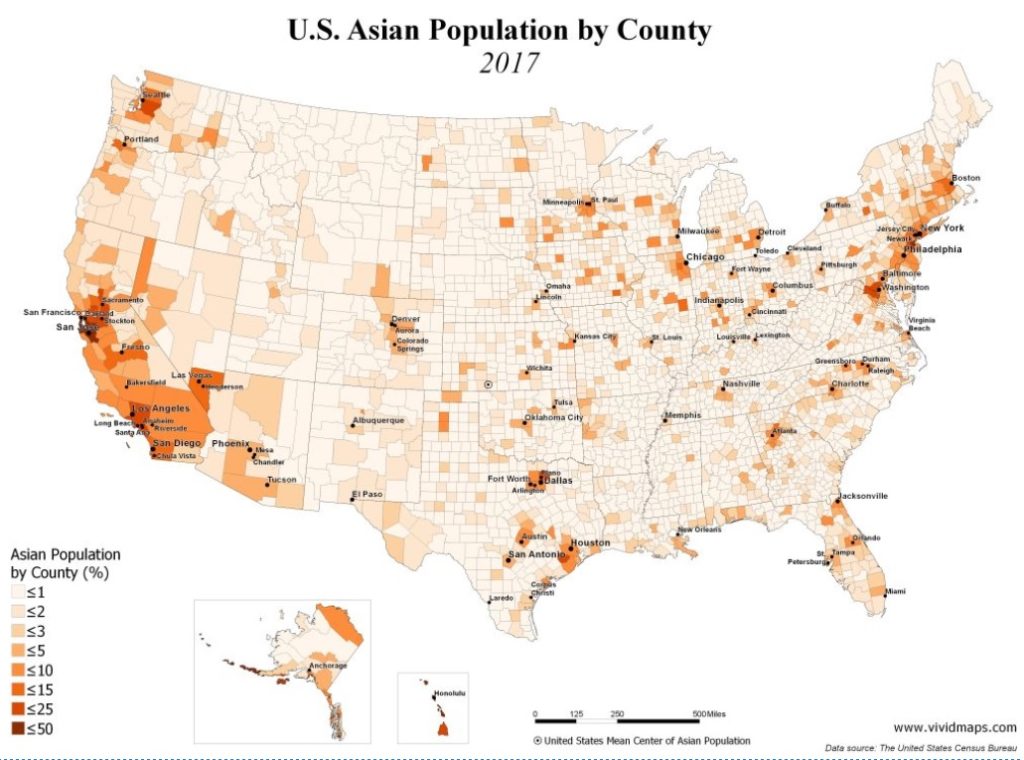

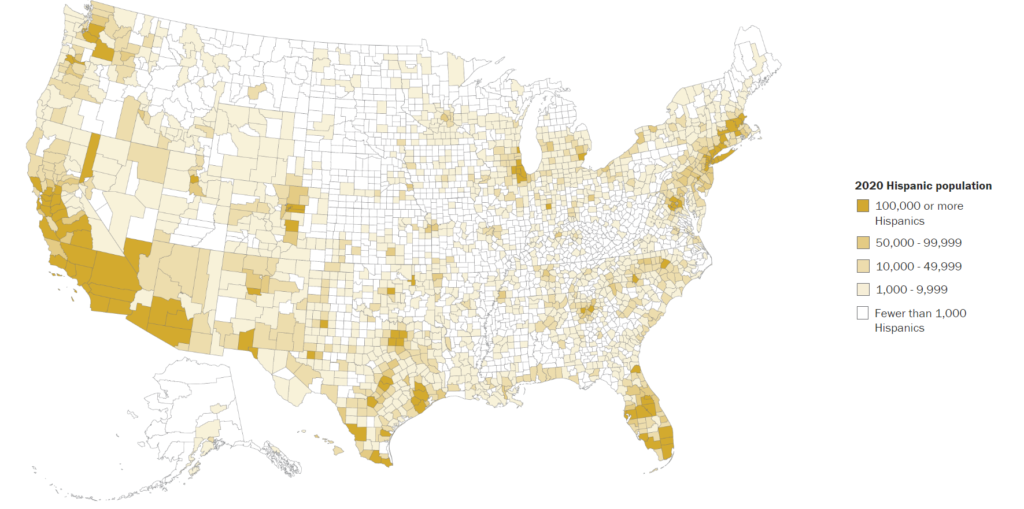

Latinos and Asians have been in the U.S. since long before there was a U.S. Over the last few decades, however, they’re much more common in many places where they used to be rare. (See the county-level maps, below, for Census Bureau population information about Asian Americans in 2017 and Hispanic Americans in 2020.) Around the turn of the millennium, the Walmart near my in-laws’ home in the Smoky Mountains started carrying chili peppers, plantains, edible cacti, and Tejano CDs. About the same time, an older woman in our church who spent most of her time at home commented to me about the demographic changes in Holland, Michigan, where I live. “The newspaper obituaries are full of Van Dykes and De Youngs,” she remarked, referring to the Dutch heritage of the city. “But the column on hospital births never seems to have the kinds of names I know.”

For several decades now, the White population in the U.S. has been growing slowly and aging rapidly. In 1990, White, non-Hispanic Americans accounted for 75% of the total population

Consider the consistent findings from several dozen research studies over the last decade. (Craig, Rucker, and Richeson, 2018, offer an excellent summary.) In each study, some White people read Census Bureau reports about things like the growth in mobile phone ownership; other White people read Census Bureau reports about how the U.S. is on its way to becoming a “majority-minority” nation, predicted to happen sometime in the 2040s.1 Compared with people who read about neutral topics like phones, those who read about demographic change became more concerned, on average, that White Americans are losing their dominant status politically, economically, and culturally. They scored higher on measures of prejudice against racial/ethnic minority groups and expressed more affinity for other White people. They became more politically conservative in matters related to race (affirmative action and immigration) and in matters unrelated to race (support for oil and gas drilling and for lower tax rates).

people of color

In the last few years, many Americans have come to believe that demographic change is being pushed by a small, powerful, secret group (usually said to be Jewish) that is deliberately trying to “replace” White Americans with non-White immigrants. This “great replacement theory” is decades old but has moved out of the fringes of the internet and into the mainstream of politically conservative media. One-third of all Americans now endorse this baseless conspiracy, which has been the stated motivation of young, White men who have committed mass murder in cities across the nation—Charleston, El Paso, Pittsburgh, Buffalo, and others.

But why are some White people anxious about the increase in Americans of color and how did that anxiety spiral out of control? Other experiments help answer that question. In these studies, the White participants who read about projected demographic change were re-assured that White people are likely to maintain their dominant status even if they become a minority, that they will hold on to power in spite of their numerical decline. Those participants exhibited no sense of threat, no increase in prejudice, and no shift toward conservative politics. Clearly, then, fear of losing status is at the heart of White concern over our changing demography, and an important reason overt racism has been on the rise (again see Craig, Rucker, and Richeson, 2018).

So you’re worried if white people become a minority? Why? Are minorities treated differently?

Mohamad Safa (@mhdksafa) on Twitter January 20, 2022

How some White people responded to Barack Obama’s election

Another turning point in racial attitudes in the last twenty years was the election of President Obama. At the time, many people saw his inauguration as the beginning of a new, perhaps “post-racial,” era. The results were anything but. An early indication of the difficulty many people would have with a Black president: the record number of physical threats Candidate Obama faced even before he became a serious contender for the Democratic nomination.

Political Scientist Michael Tesler (2016) did some very interesting research during the Obama presidency. He found that White people’s hostility to Black people (“racial resentment”) was a very good predictor of their attitudes toward Obama, even when using statistical controls for party identification and political orientation (liberal vs. conservative). Professor Tesler also found that having a Black man in the White House resulted in “the spillover of racialization” into other aspects of American politics. For example, one reason that the fight over “Obamacare” was even more intense than the fight over President Clinton’s much-more-liberal healthcare proposal is that the Obamacare argument became racialized. White people with high levels of racial resentment didn’t like Obamacare simply because its namesake was Black. That was true for other policies Obama proposed, and even for attitudes about Bo, the Obama family dog. Toward the end of Obama’s first term, Tesler (2012) predicted our current political polarization, writing that “[Obama’s] presidency could usher in a new contemporary high point for the influence of racial considerations in American politics.”2

One manifestation of that was the “Tea Party,” a grassroots protest against Obama’s agenda that erupted shortly after he took office. Racist attitudes were a good predictor of Tea Party support during the Obama years (Tope, Pickett, and Chiricos, 2015; Knowles et al. 2013). Many Tea Party members were, quite simply, furious that we had a Black president. Some of the Tea Party’s most prominent issues were inherently racialized, including their strong opposition to immigration and their concern that government programs disproportionately benefit Americans of color. Beyond the issues they championed, their intense anger and their belief that the U.S. is in decline because of increasing ethnic diversity helped pave the way for our current polarization.

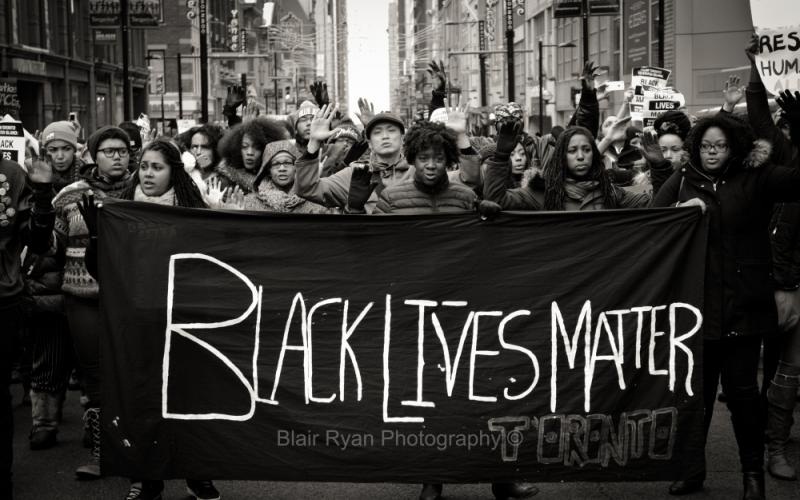

How some White people responded to Black Lives Matter

Meanwhile, as racist attitudes and values were becoming more mainstream, especially among political conservatives, many other White Americans were moving in the opposite direction. In part, this was a result of the Black Lives Matter movement that started in 2013 after George Zimmerman was acquitted of the murder of Trayvon Martin. Over the next several years, #BLM brought increased attention to the deaths of Michael Brown, Tamir Rice, Sandra Bland, and so many others. During the 2010s, many White people began to question the placid pleasantries of The Black History Month Story and started noticing racism in criminal justice, housing, education, healthcare, and other aspects of society. In addition, White Democrats became more concerned about racism during the years Donald Trump was president. At the beginning of his term, 53% of White Democrats said it was “a lot more difficult” to be Black than to be White in the U.S. By the end of his term, that figure was 70%.3

Then came 2020. The murder of George Floyd triggered Black Lives Matter rallies across the nation. Millions marched. For a few weeks that summer, more White Americans supported BLM than opposed it (which hadn’t happened before and hasn’t happened since). Hundreds of corporations, politicians, universities, churches, and other organizations issued statements supporting BLM and vowing to work against racism. Simultaneously, the Covid-19 pandemic laid bare the economic and health inequities that have beset people of color for generations. Many people believed we were on the verge of a new era in which racism would be discussed and addressed.

Living in the Backlash

But by the time 2020 ended, Shereen Marisol Meraji and Gene Demby, co-hosts of the podcast “Code Switch,” called it “the racial reckoning that wasn’t.” 2021 turned into the year of the backlash. Racial progress is often followed by an intense period of re-asserting White supremacy in a new form. After the Civil War, for example, racist ideologies were strengthened, not weakened, in order to find new ways of subordinating Black people after slavery ended (Smedley, 2007).

After the apparent racial awakening in 2020, those with a stake in White dominance got busy putting things back in order. People who had no idea what Critical Race Theory is started accusing teachers of using it to indoctrinate students and make White children feel bad about themselves. School boards and state legislatures banned books and the teaching of just about anything that acknowledged racism past or present.4 (See here and here.) States and counties enacted laws designed to make it more difficult for people of color to vote. And new congressional districts were drawn to water down the votes of people of color. Partisan polarization became even more extreme with regard to race. By large majorities, Democrats, including White Democrats, believe that more needs to be done to ensure equal rights for minority groups, that White people have advantages that people of color do not have, and that society is better off when we acknowledge the racism in our history. By equally large majorities, Republicans disagree. As of this writing, 82% of White Democrats support Black Lives Matter while 86% of White Republicans oppose it.

But this isn’t just about attitudes or political opinions. The rise in racial resentment, White ethnonationalism, and other forms of support for White Supremacy has had real effects on the quality of life for Americans of color around the country. Hate crimes and other forms of violence against marginalized people are up significantly. When “influencers” from politicians to athletes to celebrities tell their followers that some group of people is a threat, at least some of those followers are bound to act. The results are real, sometimes deadly.

On March 8, 2020, at the very beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic in the U.S., the term “China virus” spiked on Twitter and was picked up almost immediately by politically conservative media. That very day, online measures of racial bias using the Implicit Association Test showed a significant increase in the number of people who indicated that Asian Americans are less “truly” American than White Americans. This was especially true for people who identified as political conservatives, presumably, at least in part, because they were the ones most likely to have been exposed to the term “China virus” (Darling-Hammond et al., 2020).

Reports of anti-Asian hate incidents quickly followed. On March 19, the Asian American Studies Department at San Francisco State, in alliance with community organizations, began collecting data about harassment, bullying, and other acts of hate directed toward Asians in the U.S. They received 600 reports the first week and nearly 1,500 reports the first month. Over the next two years, they documented 11,500 anti-Asian hate incidents across the nation. Most took place in public, on streets, sidewalks, and in businesses like grocery stores and pharmacies. Such events can lead to both physical and mental trauma. By 2021, half of all AAPI (Asian American and Pacific Islander) people in the U.S. reported that they felt unsafe leaving home. Two-thirds were concerned about the safety of family members, including children and seniors.

There are plenty of other examples. In 2021, antisemitic incidents (harassment, vandalism, and physical assault) were up 34% over 2020, reaching the highest level recorded by the Anti-Defamation League since they began keeping records in 1979. In 2018, 38% of Latino Americans surveyed by the Pew Research Center reported experiencing at least one act of discrimination in the previous year, and the darker their skin color, the more likely they were to have been discriminated against. In 2021, the Government Accountability Office of the U.S. Congress reported that one school child in four reported experiencing bullying related to their race, national origin, religion, disability, gender, or sexual orientation. For a national perspective, see the 2020 FBI hate crime statistics here.

And that’s where we are. Going backward and forward on numerous fronts simultaneously. So many people committed to hate and so many people who want to do better. Once we understand Our Context and Ourselves, we can talk about Our Options–how to get from where we are right now to where we need to be in the future.

The Bottom Line: The last two decades have seen a dramatic shift in White American attitudes and beliefs about race and racism. Many more people, especially Republicans, are embracing racism and many more people, especially Democrats, say they want to embrace anti-racism. (Of course, saying and doing are two different things. See what former Minneapolis mayor Betsy Hodges says about that here.) Differences in attitudes about race fuel much of our current political polarization and there is no clear path to bridge the divide.

FOOTNOTES:

- As we have seen, the definitions of race have changed regularly throughout our history. In particular, the definition of who is White has broadened over time to include Jews, the Irish, and others. The prediction that the country will become majority-minority is based on the assumption that our racial categories won’t change this time. Given our history, I wouldn’t bet on it.

- Mark Ramirez and David Peterson (2020) have demonstrated that the rising number of Latina/o people in the U.S. has had a similar racializing effect on politics, especially with regard to immigration, crime, and voting rights.

- The Trump presidency itself had a significant effect on White levels of prejudice against all kinds of people on the margins—Muslims, ethnic minority groups, sexual minorities, etc. People who supported Trump became more prejudiced during his time in office, responding, in part, to their belief that such prejudice had become more socially acceptable (both on a national level and among the people they know). People who opposed Trump became less prejudiced. They also reported that prejudice had become more widespread nationally, but not among their social group. See Ruisch, B.C. & Ferguson, M.J. (2022).

- In a brilliant analysis, Presbyterian Church in America pastors Duke Kwon and Gregory Thompson (2020) argue that White supremacy is theft: theft of the labor, wealth, and power of people of color. Inevitably, another theft is then required—the erasure of any truth that would expose the original thefts.