In Part 1, we examined the rise of overt bigotry against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) during the pandemic, including terrible, terrible violence, often aimed at women and older people. In Part 2, we will examine why.

The answer begins in our history, in the role people of Asian descent have played in this country for nearly 200 years. There is a ready-made narrative about Asians in the U.S., sometimes kept in the background, but always available when it would be useful—or emotionally satisfying—to find a scapegoat to punish.

Prof. Soong-Chan Rah of Fuller Theological Seminary wrote some years back that in the U.S., Asians are viewed both as a “pet” and a “threat.” They are seen as a pet, for example, when Asian women are fetishized, or when held up as a “model minority” in order to shame other people of color and argue that racism is dead. But they are perceived as a threat when others consider them inscrutable, sinister, untrustworthy, clannish, and—in particular—perpetually foreign.

Political Scientist Claire Jean Kim (1999) says this is racial triangulation: “Valorizing” Asians in order to keep Black people at the bottom of the racial hierarchy (i.e., Asians as “pets”), but simultaneously ostracizing Asians as “immutably foreign and unassimable” (i.e., “threats”). This has been going on since the mid-19th century when Asians first arrived in North America in large numbers; it serves, of course, to maintain White dominance over both groups. If Black people are believed to be inferior, but American, and Asians are seen as less inferior, but foreign, then White people clearly deserve to be in charge. Accusations of both inferiority and foreignness are weapons, always at the ready.

Researchers have called perpetual foreignness “identity denial.” No matter how much Asian-Americans identify as Americans, no matter how American they may feel, the dominant society denies them that identity. Psychologists Sapna Cheryan and Benoȋt Monin (2005) examined the effects of identity denial among Asian American students at Stanford University and found that, in their sample,

- Asian Americans report feeling just as American as White Americans do.

- They realize, however, that White Americans do not perceive them as American.

- They know this because identity denial is a common occurrence in their daily lives. They regularly get questions like, “Where are you really from?” and “Do you speak English?” (Imagine feeling a need to ask, “Do you speak English?” of someone studying at Stanford . . .)

- In response, Asian Americans try to bolster their Americanness in their interactions with others. They emphasize their understanding of American culture and assert their pride in being American.

Cheryan and Monin go on to note that “even though large waves of Chinese Americans and Irish Americans arrived around the same time, descendants of these 19th century Chinese Americans are considered far less American than their Irish American counterparts.” That assertion was supported by Devos and Ma (2008). They told research participants that Lucy Liu, an actor, is American and that Kate Winslet, another actor, is British. The participants reported that information accurately when asked about it later. However, when taking an Implicit Associations Test, which measures implicit bias, they were more likely to connect the concept of Americanness with Winslet, who is White, than to Liu, who is of East Asian descent.

As Li and Nicholson (2021) remind us, a model minority is still a minority—minoritized, if you will, by the dominant group who can accept or dismiss them as they wish.

There is another, more sinister, explanation for the rise in anti-AAPI bigotry: public officials and others who deliberately blamed China for Covid-19, either directly or by implication. Dhanani and Franz (2021) studied these effects experimentally. When research participants read about the health threats from the coronavirus, they did not subsequently express greater bias against Asian Americans or show an increase in xenophobia generally. However, when the researchers mentioned that Covid-19 began in China, and linked it to food markets there, participants did express greater bias against Asian Americans, greater xenophobia overall, and were more likely to believe that healthcare and financial resources should be reserved for U.S. citizens rather than immigrants.

Darling-Hammond and his colleagues (2020) tracked the same thing in real life. The Trump Administration down-played the virus for as long as it could, but when faced with the real possibility of a pandemic, they changed their rhetoric and began calling Covid the “China Virus.” That phrase, and others like it, went viral immediately. On a single day—March 8, 2020—there was a 650% increase in the use of terms like “China virus” on twitter. The following day, March 9, there was an 800% increase in such terms in conservative media outlets. And March 9 was the day that implicit bias tests given online by Project Implicit began to show an increase in the number of people who subconsciously identified Asian Americans as foreigners. That was true, on average, for all non-Asians who took the test. It was especially true for White people, truer yet for White people who described themselves as politically conservative, and truest of all for those who said they were “extreme conservatives”—presumably the people most likely to consume news with a conservative slant and to follow conservative voices on social media.

The really big picture

Priya Shimpi and Sabrina Zirkel (2012) note that White Americans’ views of Chinese Americans have been remarkably stable over the last 150 years. Comparing newspaper articles, editorial columns, and other public writings about Chinese Americans from the 19th and early 21st centuries, Shimpi and Zirkel found three persistent themes in White perspectives: the Chinese work hard, but are boring, one-dimensional automatons; they stick to themselves and aren’t interested in getting to know anyone else; and because they are different from the majority, their loyalty and patriotism are suspect. In spite of the rich and varied nature of Chinese American personalities, perspectives, and experiences, these beliefs are stuck, somehow, in our national consciousness.

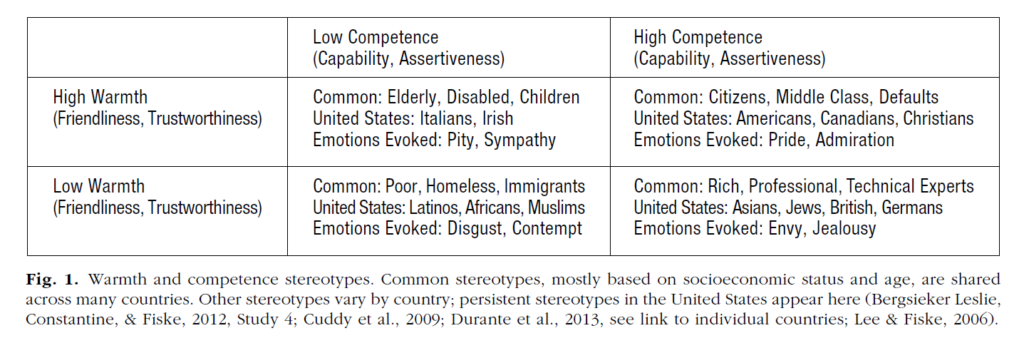

Cuddy, Fiske, and Glick (2007) find that views of Chinese Americans (and, by extension, other people of East Asian descent) are an example of BIAS: Behaviors from Intergroup Affect and Stereotypes. BIAS explains the ways our impressions of others are shaped by two primary factors: perceived warmth and perceived competence.

- Do we think a group of people is warm and trustworthy? That is, are their goals compatible with ours? Are we on the same side?

- Do we believe them to be competent and hard-working? The kind of people who can get something done when they put their mind to it?

Our answers will fall along a continuum, of course, but if we think in terms of yes/no responses to these two questions, we can see that stereotypes of other groups would fall into one of four broad categories (Fiske, 2018):

As you can see in the table, we can get pretty emotional out this stuff, resulting in pity, pride, contempt, or—in the case of stereotypes of Asians—envy and jealousy. Fiske explains it like this:

Specific stereotype content in turn predicts specific emotional prejudices on the basis of social comparison and attributions for outcomes (Fiske et al., 2002). A cooperative in-group’s or ally’s positive outcome evokes pride, while a competitive out-group’s positive outcome provokes envy. An ally’s negative outcome evokes pity, whereas a competitor’s negative outcome provokes contempt. These emotions predict behavior even better than stereotypes do (Cuddy et al., 2007).

As you can see, stereotypes of Asians are nuanced and complex. As we saw in Part 1, however, their effects are real and sometimes deadly. The most important question awaits, then, in Part 3: how do we use this knowledge to stand up for our AAPI sisters and brothers and become their allies in the fight for full citizenship and equal rights?