Our grandson turned four a few weeks back, and was happy to show me the birthday crown he got to wear at pre-school that day. His pre-school is part of a Spanish-immersion elementary school, and his crown had “Feliz Cumpleaños” written across the front. I began to sing Feliz Cumpleaños to him, and he got a quizzical look on his face. His eyes narrowed, he cocked his head, and finally he asked, “Do you go to preschool?”

He was surprised, obviously, that I know a bit of Spanish because Spanish, to him, is something that happens at pre-school, like rest break, snack time, and recess. If Grandpa can sing “Feliz Cumpleaños a Ti,” well, he must have picked it up at pre-school.

His question is an excellent reminder that we all live in, and often are bound by, a particular context. We rarely draw the lines from the past to the present. As a rule, then, we receive our context more or less as it was given to us.

That’s especially true when it comes to understanding race in the U.S. We take the concept of race for granted, not realizing that it was invented at the height of European colonial expansion as a justification for genocide and slavery. We believe our racial categories to be an inherent and immutable aspect of humanity, not knowing that many countries have categories that are quite different from our own. We assert that it’s natural for people who have important things in common to live, study, and worship together, without asking why skin color, of all things, got to be such a fundamental mark of difference.

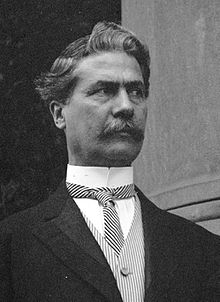

Former Housing and Urban Development Secretary Julián Castro, currently running for the Democratic nomination for president, has helped us understand more about the context of contemporary immigration law by pointing out that while being in the U.S. without papers is a civil offence, crossing into the U.S. without papers is a criminal misdemeanor. Section 1325, as it’s known, became federal law in 1929, sponsored by South Carolina Senator Coleman Livingston Blease, known as a hard-core racist even in an era of hard-core racists.

Blease proclaimed himself a champion of the White working class, even though his policies favored the business elite. He spoke of people of color in vile and dehumanizing ways, supported the anti-immigration proposals of the day, and advocated the lynching of Black men (promising, when he was governor, to pardon any White man convicted of the crime). His language was so crude that newspapers often wouldn’t quote him directly.

Section 1325, then, was the brainchild of one of the worst of the many racists who have served in the U.S. Senate. Many of the other anti-immigration measures of the day were repealed in the 1960s, but Section 1325 remained. It was largely ignored for decades; people who crossed without papers were returned back across the border, but not charged with a criminal offense. It was the George W. Bush administration that started enforcing the act, 70 years after it was passed, treating those who crossed the border as criminals, a practice that continued under President Obama and accelerated, with great fanfare, under President Trump.

That’s why parents who cross the border today are detained as criminals. That’s why their children are taken away and placed in detention camps that, by all accounts, can be filthy and dangerous. There are photographs of children in cages, reports of toddlers fending for themselves or being cared for by older children. The American Psychological Association says that these children are at risk for PTSD and other mental health disorders. The American Academy of Pediatrics says that the government is failing to meet even basic health standards.

Nonetheless, the president’s conservative Christian base and Fox News—by most accounts the only groups to whom he listens—remain silent and supportive. (Many other people of faith have spoken out, however. You can see just a few such examples here, here, and here.)

We find all this stunning because, as usual, we don’t know the context. We don’t know when border crossing was criminalized, or why, or by whom. We don’t understand that our immigration laws are neither politically neutral nor morally benign. Because we sanitize the past, and underestimate its influence over the present, we can’t draw the very direct line between 1929 and 2019.

As usual, Ta-Nehisi Coates has something important to offer. In recent congressional testimony on another race-related topic, reparations, he helped draw the line between the racism of the past and the racism of the present. He articulated the collective responsibilities of the nation and its citizens to dismantle racist foundations and move toward an anti-racist future.

“It was 150 years ago and it was right now. . . The matter of reparations is one of making amends and direct redress, but it is also a question of citizenship.”

Drawing the lines between the past and the present is the pathway to understanding our context. Re-drawing the lines from the present to the future is the pathway to racial justice.