A former president of Hope College, Dr. John Knapp, tells a story about two friends, a giraffe and a rhinoceros. The giraffe built a new house She loved the high, narrow doorways, the top-of-the-wall windows, and other features that made it the best house ever. She was excited to show it off to the rhino, and set a date to have him over.

You can imagine the rhino’s experience. He couldn’t get through the doors, couldn’t see out the windows, and was generally miserable. The giraffe was confused, and more than a little hurt, that the rhino didn’t seem to enjoy himself and left while the night was still young.

Dr. Knapp’s point, of course, is that every institution is built and shaped according to a set of assumptions about the people who will inhabit it. Formal regulations and informal practices–both the visible and invisible culture of the place–will work better for some than for others. To the extent that the organization has been racially, ethnically, or culturally segregated, it was designed for people from a particular slice of the population. People from other slices may not fit very well. They may not thrive. They may well have a hard time even getting in.

Our first step is to realize that the “buildings” we inhabit, the institutions of which we are a part, were constructed. They were created by people who had specific goals and aspirations in mind. They made decisions about purposes, policies, and procedures. They established the social norms. That’s true for your local Rotary, for the National Rifle Association, even for the nation as a whole.

When it comes to race and racism, however, there are many people who absolutely do not want to acknowledge that the present is rooted in the past. They deny that the home in which we live was built with intention and purpose, arguing, instead, that it’s simply the natural way of things, the way things are supposed to be. But all of U.S.history–not just The 1619 Project, Critical Race Theory, and Stamped from the Beginning–is evidence that our nation and its institutions were shaped, quite deliberately, to nurture and perpetuate racism. It only stands to reason, then, that if our institutions were modeled for racism, they can be remodeled for anti-racism. And remodeling is exactly what those who support the status quo don’t want.

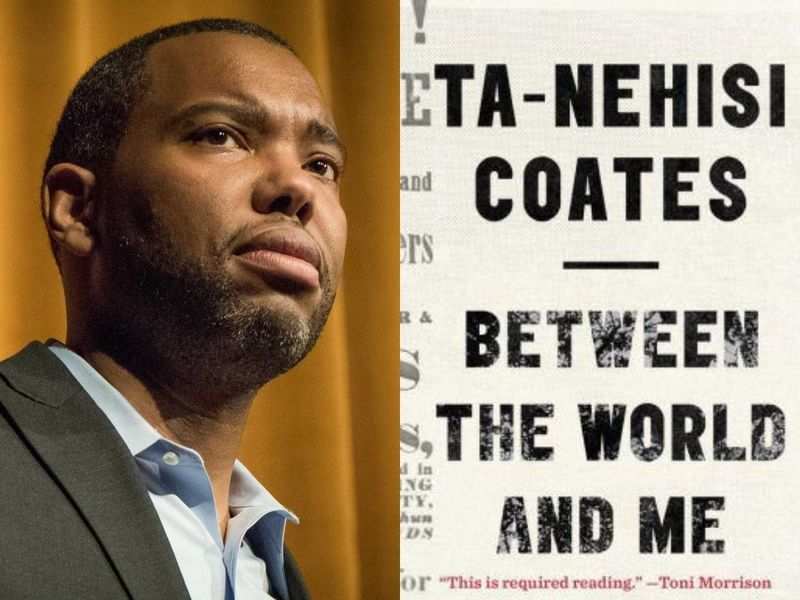

Ta-Nehisi Coates writes about this in his brilliant book, Between the World and Me (2015):

“Americans believe in the reality of “race” as a . . . feature of the natural world. . . . racism is rendered as the innocent daughter of Mother Nature, and one is left to deplore the Middle Passage or the Trail of Tears the way one deplores an earthquake, a tornado, or any other phenomenon that can be cast as beyond the handiwork of men.

“But race is the child of racism, not the father. [It] has never been a matter of genealogy and physiognomy so much as one of hierarchy. Difference in hue and hair is old. But the belief in the pre-eminence of hue and hair, the notion that these factors can correctly organize a society and that they signify deeper attributes—this is the new idea at the heart of these new people who have been brought up hopelessly, tragically, deceitfully, to believe that they are white.”

We begin the work of making a difference, then, by realizing that if racism was created, then anti-racism can be created, too. There are ways to dismantle racism productively, ways to make things work well for a broader range of people. It doesn’t have to be a zero-sum game. Thoughtful analysis, creative thinking, and a strong commitment to justice can help an organization–and even the nation as a whole–improve performance and become more inclusive at the same time.

We can welcome symbolic victories along the way, but we have to stop confusing symbolic victories with actual progress. As I write this, the federal government has just made Juneteenth a national holiday. Sounds like a good idea to me. But literally hundreds of people in congress voted for it who have opposed any and all reasonable efforts to turn the government and the nation against racism, to live up to our own ideals, to remodel our institutions, and make a real difference. That kind of brazen hypocrisy is made possible when we decide to add a little veneer across the top instead of re-working the foundation underneath.

Ethicist Jonathan Tran warns us that this happens, too, with antiracism efforts themselves. Diversity offices in companies, universities, non-profits, school districts, church offices, and elsewhere are tasked with making their institution less racist. But often everyone knows that they have little power and few resources. The powers-that-be have no intention of becoming the powers-that-used-to-be, leaving official antiracism leaders little room to make a real difference. Prof. Tran:

“These antiracist initiatives, often staffed by well-meaning and high-minded people, bring with them all the conviction but little of the power to actually get anything done, at the end of the day achieving so little that one begins to wonder if futility was the point.”

We know that significant change takes a whole lot of work and, usually, a pretty long time. The trick, then, is to aim our work right at the heart of systemic racism so that the progress we do make can result, over time, in meaningful change rather than window dressing.

There is a lot of racism in our history. At the same time, our history gives us the tools for dismantling racism. Michael Gerson, who was a speechwriter in the George W. Bush administration, says it like this:

“Though our nation is beset with systemic racism, we also have the advantage of what a friend calls “systemic anti-racism.” We have documents — the Declaration of Independence, the Bill of Rights, the 14th Amendment — that call us to our better selves. We are a country that has exploited and oppressed Black Americans. But we are also the country that has risen up in mass movements, made up of Blacks and Whites, to confront those evils. The response to systemic racism is the determined, systematic application of our highest ideals.”

Even the loud, ludicrous, nasty, frantic backlash to antiracism we see all around us in these times may have a silver lining. Writing for Religion News Service, Andre Henry says,

“The current hysteria in the U.S. about the growing influence of antiracist ideas is a good sign in the struggle for racial progress. It suggests that last year’s uprising for Black lives successfully knocked America’s white supremacist common sense off balance. Every bill that attempts to ban Nikole Hannah-Jones’s 1619 Project from school curricula, every seminary statement repudiating critical race theory, every Tucker Carlson rant about the existential threat of ethnic studies programs is a desperate attemtp to regain equilibrium for white cultural hegemony.

It’s tempting to see this backlash as a move from strength, but consider the conflict from the opponent’s view. If the custodians of the status quo saw themselves in a position of strength, they’d still be doing with critical race theory what they’ve been doing since the discipline emerged in the 1970s: ignoring it.”

Thank you for wanting to make a difference. I am grateful.