I’m not a big fan of small steps. I like large steps. Strides. I want a blueprint for Ending Racism in Our Time, and No Later than Tuesday Afternoon. With all that needs to be done, who has the patience for small steps? Besides, small steps often are used as an excuse to declare victory, send everyone home, and insist that those who want more simply can’t be satisfied.

But I was heartened by two small steps last week, and reminded that the right kind of small steps can be an important and effective part of working for racial justice.

In 1838, Georgetown University, the nation’s first Roman Catholic college, was in trouble. Financed by Jesuit plantations in Maryland that were becoming less and less profitable, money was short. Georgetown’s president at the time, Thomas Mulledy, S.J., sold 272 slaves, using the profits to pay down debts and establish a firmer financial foundation for the school. The enslaved persons were shipped to plantations in Louisiana, where many were severely mistreated, families were separated, and some were denied the right to practice their faith. Mulledy later regretted his decision, but what was done was done.

Under current Pres. John DeGioia, Georgetown is considering how best to acknowledge the fact that the university owes its existence to slave labor and slave profits. It is far too late to compensate the enslaved people whose lives were ruined for the profit of others. But it’s not too late to tell the truth, and to act on the implications of that truth. (For example, they have begun the Georgetown Slavery Archive in order to gather more information and connect with descendants of the enslaved people.)

Last Monday, Pres. DeGioia met with Ms. Patricia Bayonne-Johnson, an amateur genealogist and a descendent of Nace and Biby Butler, two of the people sold by Georgetown University 178 years ago. They talked, and shared lunch, and contemplated what, if anything, the university might do now. “It was a very good beginning,” Ms. Bayonne-Johnson said. A small step.

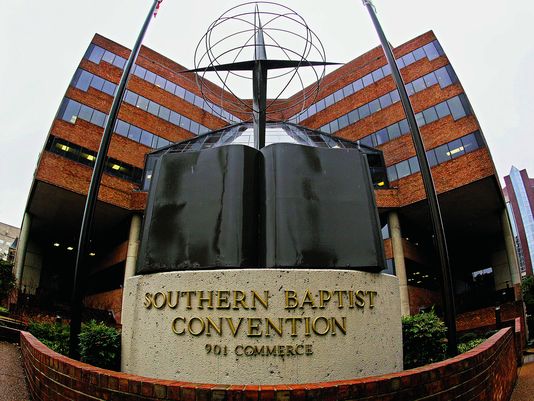

The Roman Catholic Church is the nation’s largest Christian denomination. The second-largest, the Southern Baptist Convention, has a history even more overtly intertwined with slavery and the war that ended it. During their annual meeting last week, they considered a resolution asking members “to consider prayerfully” whether they might limit displaying the Confederate Battle Flag—and, just maybe, think about not displaying it at all. To make that very small step even smaller, the resolution went out of its way to state that the flag has historical meaning and, for some, is not a symbol of racial bigotry.

Those at the meeting, however, saw the resolution for the mealy-mouthed insult it was, and they strengthened it considerably. By a wide margin, the delegates voted for a resolution calling on Southern Baptists to “discontinue the display of the Confederate battle flag,” and to do so “as a sign of solidarity with the whole Body of Christ, including our African American brothers and sisters.” Former SBC President James Merritt reminded the meeting that “Southern Baptists are not a people of any flag. We march under the banner of the cross of Jesus and the grace of God.”

Small steps, yes, but the right kind of small steps. Why? Because they help us see the world from someone else’s perspective, to understand a bit better how someone else’s experience has shaped their beliefs and attitudes.

Psychologists have been talking about perspective-taking ever since Jean Piaget described its importance in child development. Essential to all successful communication, it is especially helpful in increasing the “overlap” we can see between ourselves and another person, even when that person is different from us in an important way. Interestingly, while looking at the world from another person’s perspective is something that most of us have the ability to do, we don’t generally do it automatically, and we often have to be reminded or prompted to do it.

Social Psychologists Adam Galinsky and Gordon Moskowitz (2000) found that asking young people to take the perspective of an older person was an effective way to get them to think about that person in a non-stereotypical way, significantly more effective than specifically telling them not to stereotype. Andrew Todd and his colleagues (2011) found that asking non-Black research participants to take the perspective of a Black man experiencing discrimination led them to stereotype Black people less than those who were asked to provide an “objective” report of the situation. The overlap between self and other induced by perspective-taking resulted in a more positive view both of the individual person and of the social group to which he belonged.

Perhaps, then, one way to differentiate between small steps that will and won’t make a difference is to ask this question: Do they prompt us to take the perspective of someone else, someone whose experiences and identities are different from our own? If the answer is no, then don’t get too excited. But if the answer is yes, then make good use of the opportunity to understand others better, to see the overlap between your self and theirs, and to get beyond stereotypes in thinking about their social groups.

Talking about the sale of enslaved persons nearly 200 years ago is a small thing relative to the tragedy itself. So is asking Christians not to display the Confederate flag. But they both exemplify efforts to take the perspective of someone else, and both contain, therefore, the possibility of affirming the shared humanity with people we otherwise might be tempted to disparage or ignore.

Charles W. Green