“Whiteness, like other forms of domination, is characterized by masking power under a veil of normality.” –Glenn Bracey and Wendy Leo Moore, 2017

My wife is an avid gardener. It’s her favorite thing about summer, and she tends to it daily—planting, watering, pruning, fussing around. Lots of people compliment the yard, but they don’t realize how much time, care, and devotion it requires. If we’re gone even for a week or two, you can tell it has suffered from lack of attention.

The care and upkeep of social organizations requires a lot of attention, too: reinforcing norms, fine-tuning goals, maintaining boundaries. Casual observers don’t realize how much time, care, and devotion it requires.

Glenn Bracy and Wendy Leo Moore (2017) have studied the care and upkeep of organizations—specifically the work required by segregated White churches to maintain their all-White status. There aren’t many people of color trying to get in, but when one shows up, it takes effort to make sure everything turns out all right.

In spite of recent increases in overt expressions of White supremacy, even the most segregated White church would be unlikely to put up “Whites Only” signs. Turns out they don’t have to. There are other ways, equally effective, of maintaining segregation beneath a façade of race neutrality.

The key is to mark one’s turf, as clearly as possible, as what Bracy and Moore call a “White institutional space.” Steeping the organization—policies, practices, leadership, etc.–in White culture keeps a lot of people of color out. But there are other ways of tending the garden of segregation, too, when necessary.

We’ve heard a lot in recent years about micro-aggressions, those small, daily insults and jabs suffered by people of color, women, and other marginalized groups (Sue, 2010). The concept is controversial. For some, it is a concrete reminder of the pervasiveness of their marginalization. For others, it is political correctness gone amuck, proof that the real problem is that some people are hyper-sensitive, and the rest of us are being told we have to accommodate to their petty needs.

As sociologists, Bracey and Moore understand the macro-social factors that shape White institutional space in churches, including historical differences in doctrine and worship, residential segregation, and the nature of the religious marketplace. But the particular insight they offer is to see micro-aggressions as the means by which macro-segregation is maintained and enforced.

Mr. Bracey is a young African American man, “a devout Christian with extensive history in evangelical and conservative Protestant churches.” Doing ethnographic field work, he visited seven White evangelical churches to see what kind of reception he would receive. (That’s the trade-off you make in this kind of research—lots of rich information, but a small sample size, and no control group for comparison.) White evangelicals are interesting to study when it comes to race, because, as a group, they both reflect and magnify the broader White culture. Some non-evangelicals like to think that evangelicals are different from other Whites in fundamental ways. Truth is, when it comes to racial attitudes, White evangelicals (with lots of exceptions, of course) are like Super-Whites who clarify and amplify broader White culture and belief (Emerson and Smith, 2000).

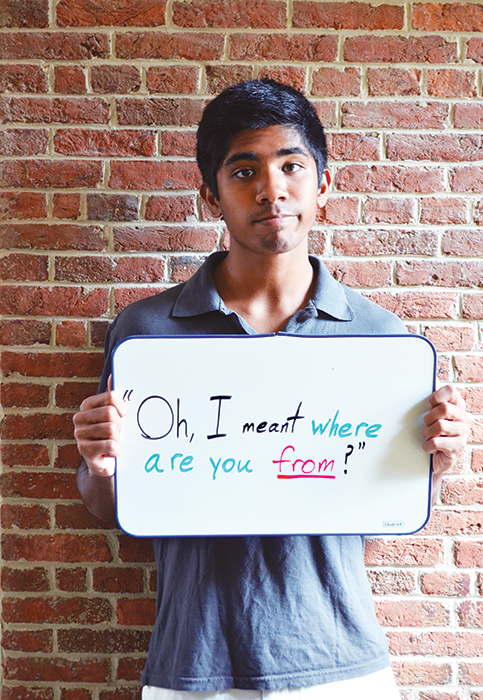

In every one of Bracey’s church visits, he experienced some kind of micro-aggression, sometimes several. Over time, he came to see that the disturbing comments people made to him were something of a “race test,” designed to maintain the White institutional space. The race tests he faced were of two different kinds.

First are the “utility-based” tests, the purpose of which is to see whether a particular person of color might be of some use to the organization. A token minority member, for example, to vouch for the church’s good will toward all. Tokens, of course, must be, as Bracey and Moore explained, “small in number and small in effect.” They have to be willing to abide by the norms of White institutional space, and live within those boundaries. Utility-based micro-aggressions are designed to see if a person of color is the “right kind” of minority–a “good fit.” For example, Bracey was asked multiple times if he would be interested in singing for the church or be involved in the music ministry. This was in part stereotypical—aren’t all Black people musical?—but Bracey also came to see it as a way of channeling him into the role of entertainer, a role which helps White people feel more comfortable about having Black people around. The test, of course, is this: Will you be the kind of minority member we want you to be? Will you confine yourself to roles that help us be comfortable? Can we count on you to be a good fit?

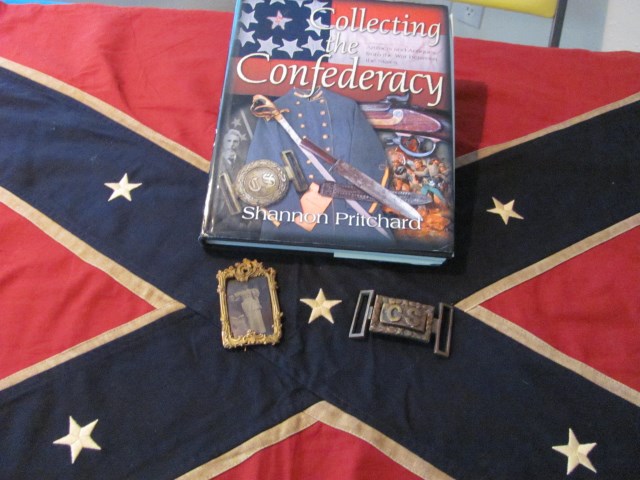

More common than utility-based tests are the exclusionary tests. This is a more severe form of boundary maintenance, designed to weed out all but the most subservient people of color, to repel any and all who might disrupt the White institutional space. For example, at one church, at the beginning of a Bible study, one member introduced himself by talking about his favorite gun—and then used his hands to pretend to shoot Bracey and the one other person of color who attended that day. In another church, as part of what initially appeared to be casual conversation, a church member spent a lot of time telling Bracey about his extensive collection of Confederate memorabilia. The obvious message in both cases: if this level of racism is OK with you, you’re good to stay. If not, better leave now.

Bracey and Moore point out that micro-aggressions serve a macro-segregationist function. They are an important way that White institutional space is tended, protected, nurtured like a garden. At an interpersonal level, they may be seen by some as merely unfortunate, but at an organizational level they are an important part of maintaining White control over White space. This is a good reminder that there is nothing natural or inevitable about White space—it is the product of careful planning and regular maintenance.

So the next time you see or hear of a micro-aggression, first offer support to the person who was targeted. But then talk with others in your organization about the broader role that micro-aggressions serve in the care and maintenance of White institutional space. The least we can do is remove the façade of race neutrality and say out loud exactly what is going on.