Anti-Asian hate crimes have been all over the news for a year now and, if anything, seem to be getting worse. They’re not new, of course, but they are on the rise, driven, almost certainly, by the pandemic and the pre-existing condition of racism. Why is that? And what does it tell us about race in the U.S.?

On February 11, 2021, USA Today reported

“Police in Oakland, California, announced this week that they arrested a suspect in connection with a brutal attack of a 91-year-old man in Chinatown that was caught on camera. In less than a week, a Thai man was attacked and killed in San Francisco, a Vietnamese woman was assaulted and robbed of $1,000 in San Jose, and a Filipino man was attacked with a box cutter on the subway in New York City.”

More recently, A 65-year-old woman was hit and kicked repeatedly near Times Square in New York City while bystanders did nothing. Several elderly Asians have been attacked in the Bay Area. Someone even stole 700 whistles volunteers were collecting to give to Asian American seniors so that they could call for help, if necessary.

And, of course, six of the eight people killed in the mass shootings in Atlanta on March 23, 2021, were women of Asian descent. The targeting of Asian women, in particular, stands out in most reports.

Violence against Asians isn’t new, of course. Asians have been threatened and attacked, especially out West, since they first came to the U.S. Historian Kevin Waite has written of the terrorism the KKK inflicted on Chinese people in California in the years after the Civil War, when Chinese immigrants accounted for 10% of the state’s population. The Klan destroyed homes, burned churches that offered services to the Chinese, and threatened the crops of any farmer who employed “even a single Chinaman.” There’s much more, sadly. You can read about the 1871 massacre and more in this article from the Los Angeles Times.

Building on that legacy of terror, the FBI predicted that violence against Asian Americans would increase during the pandemic. Sadly, they were right. The Stop AAPI Hate Reporting Center is a collaborative effort organized about a year ago to track violence and other forms of discrimination directed against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in the U.S. They received reports of 3,795 incidents around the country between March of 2020 and February of 2021. This is likely just a fraction of all the incidents, of course, but it offers a glimpse into what is happening. The Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism at California State University San Bernadino collected data from police departments in the nation’s largest cities and found that 2020 hate crimes against Asian Americans were twice as high as the 2019 numbers. Attackers were White, Black, and Latinx, suggesting that anyone can inhale the smog of cultural bigotry.

The Pew Research Center reported last July that in the first few months of the pandemic, Asian Americans already were having negative experiences:

- 39% said that other people had seemed visibly uncomfortable around them;

- 31% said they had been on the receiving end of racist slurs or “jokes”;

- And 20% said they were fearful of being physically threatened or attacked.

Consistent with these experiences, Pew also reported that 39% of U.S. adults surveyed said that it had become more common to hear racist comments about Asians in the weeks since the pandemic began. As you can imagine, all this is taking a toll. Lee and Waters (2021) surveyed 400 Asians and Asian Americans around the country. Nearly 30% reported an increase in discrimination since the pandemic. 41% reported an increase in anxiety, 53% reported an increase in depression, and 43% reported an increase in sleep problems. That was especially true for those who reported having only weak social support.

Across the country, Asian-Americans are protecting their loved ones and their communities by patrolling their neighborhoods and escorting older people as they run their errands.

On top of all this, Asian Americans are suffering from the pandemic at higher-than-average rates. The British medical journal The Lancet reported last fall that Asians in the US and the UK were 50% more likely than White people to contract Covid-19. (Sadly, Black people were twice as likely.) Asians also have been disproportionately affected economically, too. According to CNN Business, in the first two months of the pandemic, unemployment claims in New York State were up around 2,000% for non-Asian workers, but up nearly 7,000% for Asian workers, many of whom work for relatively low wages in restaurants, nail salons, and other small businesses that were hit hard by closings. Asian Americans have a high median income as a group, but the median masks the fact that no other ethnic group in the U.S. has as much disparity between the top and the bottom income earners. Kuo, Kraus, and Richeson (2020) find that our “examplars” of Asian Americans are disproportionately well-to-do, making it difficult for us to realize how many poor and working-class Asians live in the U.S.

It is common for pandemics to spawn xenophobia. In the 15th century, syphilis was called “the French pox” by the English, “morbus Germanicus” by the French, and “the Chinese disease” by the Japanese (Joffe, 1999, as cited in Li and Nicholson, 2021. During the current pandemic, some people in China have identified African immigrants as likely carriers, in the absence of any evidence whatsoever. But that begs the question, “Why scapegoat some groups but not others?”

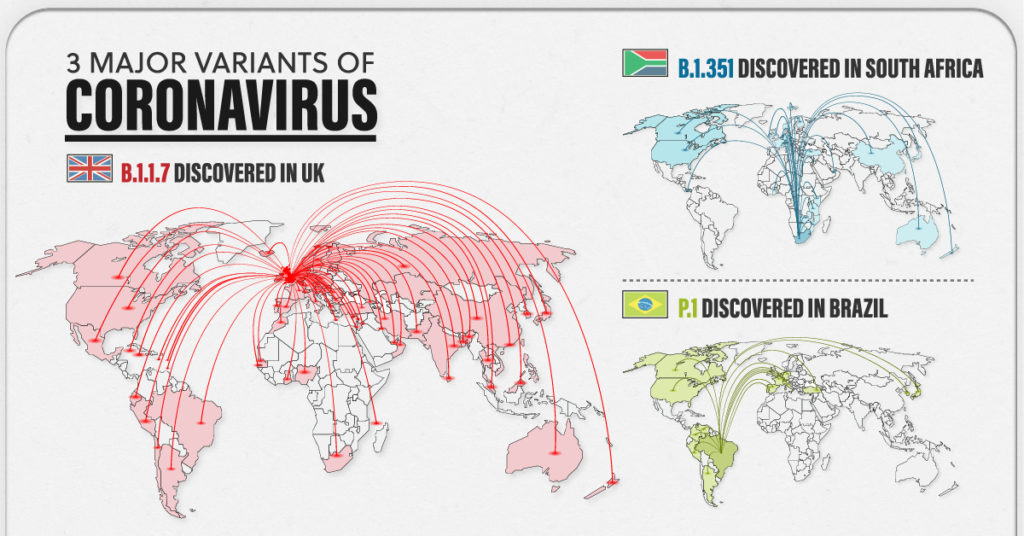

It’s true that Covid-19 was first reported in China, but it has come to North America from many different places. We’re dealing now with difficult variants from the UK, South Africa, and Brazil, with no apparent hostility toward those countries. Furthermore, in what sense are Americans of East Asian descent in any way responsible for what has happened?

One factor may well be the fact that Asian Americans are the fastest-growing ethnic group in the country, and have been for some time now. Cikara, Fouka, and Tabellini recently found that the largest minority group in a community is more disliked by the majority and is subjected to a disproportionate share of hate crimes, as well.

However, U.S. stereotypes about Asians are complicated and confusing. We need to know more about them before we can really understand the violence many AAPI Americans are facing today. That’s in Part 2, the next post.