As we saw in the section called How Did the Idea of Race Develop?, Sociologists Michael Emerson and Christian Smith (2000) describe racialization as the ubiquitous inequities of our society, the fact that in all manner of ways, White people have disproportionate access to power and resources in this country. Racialization is the work we do to make sure White people get a better deal than anybody else. It’s the time and energy required to keep White supremacy supreme.

Racism is rooted in racialization. It’s what we tell ourselves and others to explain, and explain away, racialization. It is an ideology of justification. Like racialization, racism requires regular nurture and defense. That’s why White supremacy plays offense whenever possible. 2020 saw a significant increase in the number of White people beginning to question the validity of racialization. Come 2021, then, cue the Critical Race Theory mania. Socialism! Marxism! Reverse Racism! All to ensure that those who drank the Kool-Aid remain faithful to the cult. Otherwise, those with more than their fair share of power and resources might begin to lose their priviledged status. Maintaining racialization, and justifying it with racism, is what colonialism, slavery, Jim Crow, and the current backlash to civil rights are all about: one continuous thread through time using different means toward a single end: the preservation of racialization. That’s why Saidiya Hartman (2007) of Columbia University says

“I, too, live in the time of slavery, by which I mean I live in the future created by it.”

There are many interconnected parts in this future we live in, the future created by slavery (and created, as well, by Native genocide, anti-Asian and anti-Lantix bigotry, etc.) We talked about the racialization of income and wealth in the section called The Vertical Dimension of Race: Social Power. If you haven’t seen it, you should start there. Here I will discuss, briefly, the racialization of neighborhoods and housing, education, environmental quality, and law enforcement.

Neighborhoods and Housing

In a classic article that still is sadly relevant, Social Psychologist Thomas Pettigrew (1979) wrote that residential segregation is the “structural linchpin” of racialization because it makes all the other forms possible. Sociologist Douglas Massey (2016), best known as the co-author of American Apartheid (1998), says that segregation is as high now as it ever has been, higher in many places, especially in the Northeast and the Upper Midwest. (There are some exceptions, most commonly out West.) The Othering and Belonging Institute of UC Berkely did a comprehensive study recently of residential segregation in the U.S. Among their many findings: “Out of every metropolitan region in the United States with more than 200,000 residents, 81 percent (169 out of 209) were more segregated as of 2019 than they were in 1990.”

An increase in segregation at the same time as a dramatic increase in ethnic diversity. That requires a whole lot of effort and a serious level of commitment.

According to Massey, in his 2016 article, cited above, the one change over the last 50 years is that most White people today are willing to live in a neighborhood with Black or Latinx people IF there are only one or two families of color AND those families are professional and middle class. The line has moved from absolutely all-White to virtually all-White if there are only a few of them and they meet or exceed average community levels of income and education. And because these people are open to living near a very small number of the “right kind” of people of color, I’d guess they believe themselves to be non-racist.

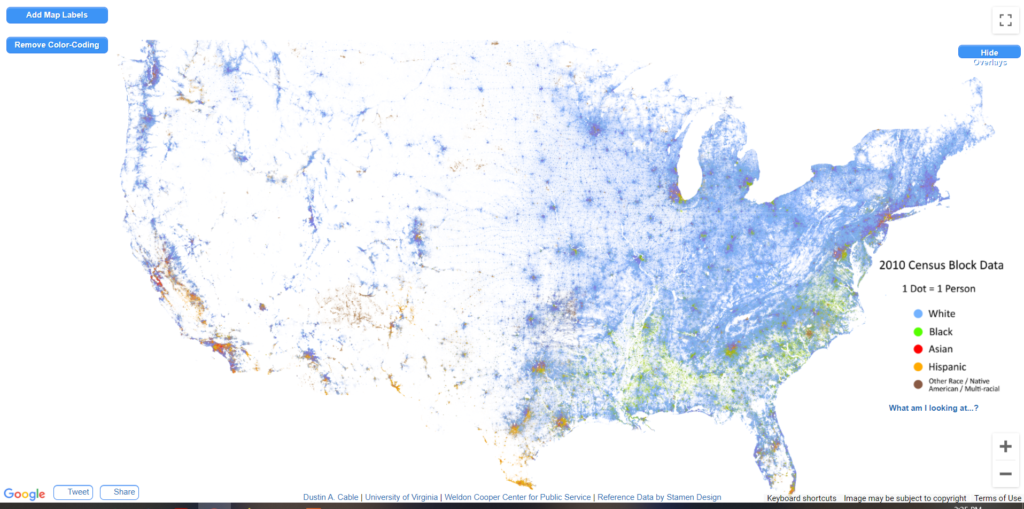

I encourage you to spend a bit of time with the Racial Dot Map of the University of Virginia. You can zoom in to see neighborhoods in every city in the country. It is a visual lesson in just how segregated most cities remain.

Segregation is related to a long list of housing disparities. Home ownership is one of them. Former Oklahoma Senator Fred Harris, the last surviving member of the 1968 Kerner Commission, used data from the Economic Policy Institute to compare the economic standing of Black and White Americans in 1968 and 2018, fifty years after the commission released its report. Harris found again and again that racialization is as bad or worse as it was in 1968, when the Kerner Commission recommended sweeping changes to bring about greater equality. Disparity in home ownership is one of them. Home ownership is up only a few points for White Americans since 1968, from 66% to 71%, reflecting the economic stagnation of the middle class over those decades. Black home ownership is up not one whit, steady at 41%.

Black home ownership was up to 48% twenty years ago, but then fell back. The Great Recession hit Black and Latinx families particularly hard. The home ownership gap is due, in part, to the gaps in income and wealth. In addition, people of color face continued discrimination in the housing market, both as renters and buyers. The Department of Housing and Urban Development conducted a national study on housing discrimination in 2012, and found that realtors often steer Black, Latinx, and Asian people away from White neighborhoods

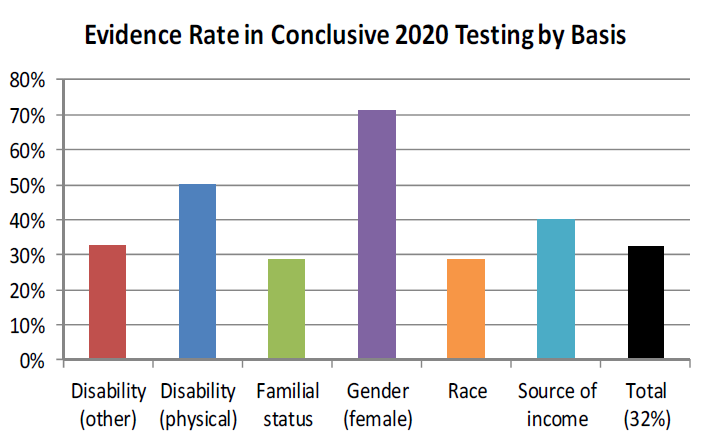

In 2020, my local fair housing center, the Fair Housing Center of West Michigan, conducted 242 tests of bias. They sent out people of different identities to inquire about renting or buying a home. They found discrimination 32% of the time—for race and ethnicity, but also for disability, family status, gender (especially gender—wow), and source of income. All across the board. Stunning and not surprising, all at the same time.

The Covid-19 pandemic highlighted the precarious situation of many homeowners of color, many of whom had not yet rebounded from the Great Recession. In July of 2020, five percent of White homeowners reported missing at least one mortgage payment that year. For Black homeowners, it was four times that number: twenty percent. Things were even tougher for Black renters. In the fourth quarter of 2020 and the first quarter of 2021, nearly thirty percent of them were behind on their rent.

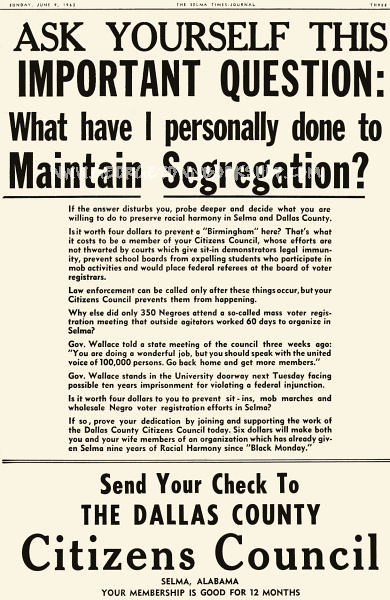

The White Citizens’ Council of Dallas County, Alabama, circulated this flier in 1963: “What have I done personally to maintain segregation?” It’s still a good question for those of us who are White. When we look for “nice” neighborhoods, “good” schools, and a church where we can feel “comfortable,” what is it we’re really looking for? A number of middle-class White people I know refer to themselves as living in a “bubble.” Generally intended to be humorous, it describes spending nearly all their time, everywhere they go, with other middle-class White people. The implication is that they just happened, somehow, to find themselves inside an economic and cultural bubble. But the truth is, they self-embubble-ated. They have personally done what was necessary to maintain segregation. The 1963 Dallas County Citizens’ Council would be proud.

Education

Same thing in schools. Most White people tell pollsters that they favor integrated schools. But most of them select segregated options for their own children. University of Southern California Sociologist Ann Owens says this:

“Once you control for all the other things parents might say they care about—economic class, test scores, resources, etc.—white parents still prefer schools serving fewer black or Hispanic kids.“

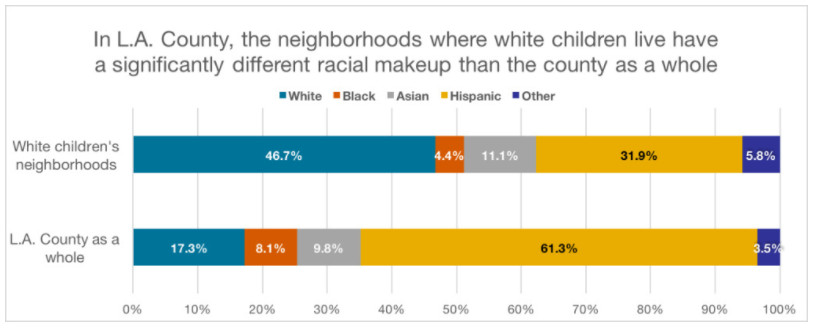

The White preference for White schools reinforces neighborhood segregation, as Prof. Owens demonstrates in this chart. In Los Angeles, White adults with children are far more likely than other White adults to live in neighborhoods with a higher-than-average number of White people.

Most of us believe that the 1954 Brown v. Board Supreme Court decision outlawed racial segregation in schools. But it only outlawed de jure (by law) segregation. When the Brown decision finally started being implemented in the early 1970s, White families by the millions began looking for all-White neighborhoods to live in so that their children could attend all-White schools.

In 1974, White suburban Detroit families sued to prevent school desegregation from crossing district lines. They also firebombed a school bus parking lot as part of their protest. And the Supreme Court ruled in their favor, thereby upholding de facto segregation. The message of the court was clear: Move to a White area, and keep it White. If you can maintain residential segregation, you get to have school segregation, too.

Similar Supreme Court decisions followed, virtually gutting Brown v. Board. The Othering and Belonging Institute of UC Berkeley has found that racial segregation now is just about what it was when the Brown v. Board decision came down:

“Schools have gradually re-segregated in the 65 years since Brown v. Board of Education was decided. The problem today is that our nation’s public schools replicate the demographic profiles of the communities and neighborhoods they serve.”

Whatever is going to preserve White parents’ access to White schools is what they say they want.

School boards are to blame for segregation, as well. Most—though not all—draw school district lines in ways that maintain the segregation of a community’s neighborhoods. It’s often possible to draw the lines in other ways so that school boundaries cut through the segregation and still send kids to a nearby school. But that doesn’t happen very often.

All this segregation leads to more resources and opportunities in largely White schools, and fewer resources and opportunities in schools that mostly serve students of color. The best predictor of one measure of educational success—standardized test scores—is family income and wealth. (Test scores are not nearly as good a predictor of success as most Americans believe, but we’ve got lots of data on them, so a lot of the research is focused there.) The relationship between family wealth and student test scores is clear in this graph from the Education Opportunity Project at Stanford University:

This is a complex issue, of course, but the main trend is clear: well-to-do (usually White) parents organize their lives—neighborhood, school, etc.—around an effort to provide their children with what they think of as the very best. I’m a parent. I understand the impulse, but it is seriously misguided. It’s bad for your kids and bad for the country. Raising your children in all-White spaces doesn’t prepare them for an increasingly diverse society. In fact, it significantly increases the odds they will absorb the racist values and perspectives inherent in segregated White places. (Your racist values, frankly, if you consistently believe that the Whitest places are, by definition, the best.) And the nation as a whole is poorer—in a variety of ways—because millions of individual decisions by White families mean that many, many people of color will live in high-poverty neighborhoods with little eonomic or social capital. These parents believe that opportunity hoarding is in their family’s best interests, but the result is that their children grow up deprived of a richer set of educational and social experiences. And in another generation or two, they will inherit a country that still doesn’t know how to get race right.

To learn more about how racism impoverishes the nation as a whole (literally and figuratively), read Heather McGee’s excellent book The Sum of Us (2021).

Even in a time of economic stagnation for the bottom 90% and increasing school segregation, students of color, for the most part, have been working hard and doing well. The U.S. Census Bureau reports that Black students graduate from high school at a rate nearly identical to the national average (around 91%), and have been for a couple of generations now. (Boys, especially Black and Latino boys, still lag behind girls in getting a diploma.) Black college attendance is just a few points behind the national average (38% vs. 41%), but Black students graduate at a lower rate (28% vs. 41%). And the Black graduation rate has been stagnant while the average national graduation rate has climbed steadily. Those of us who work in colleges and universities are on the front lines in this effort–not simply recruiting Black and other students of color, but providing them with the resources they need to graduate—and graduate without crippling levels of debt.

Environmental Quality

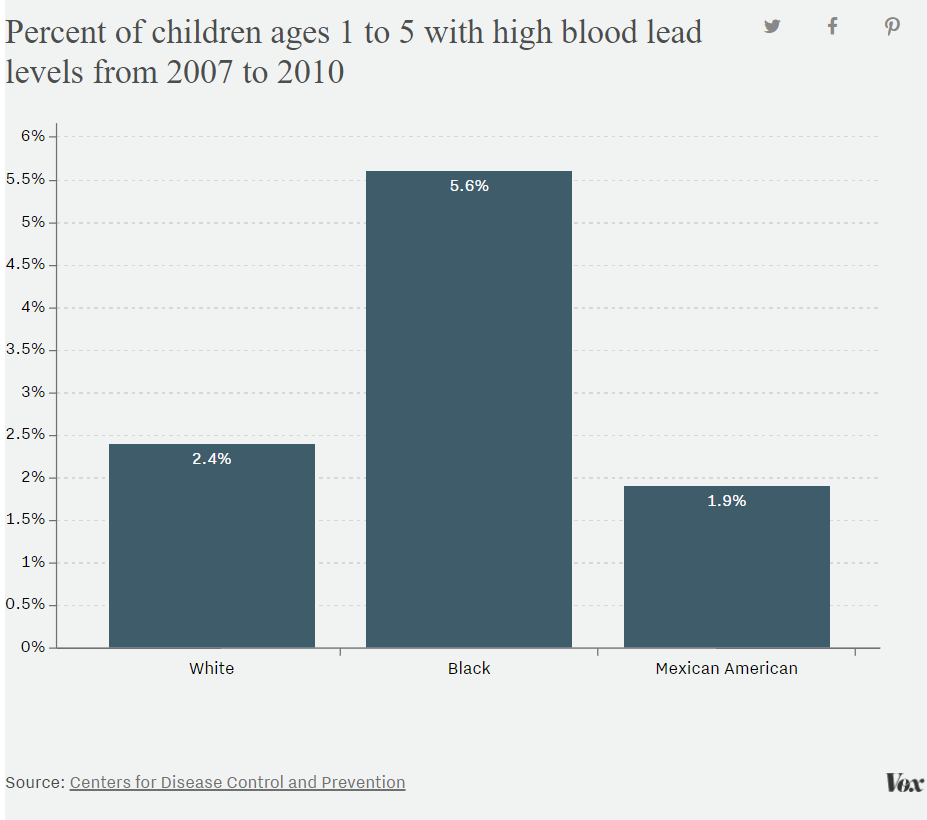

According to a report from Paul Quinn College

Black Americans (of any economic standing) are 75 percent more likely than Whites to live near a hazardous waste site. According to the Environmental Integrity Project

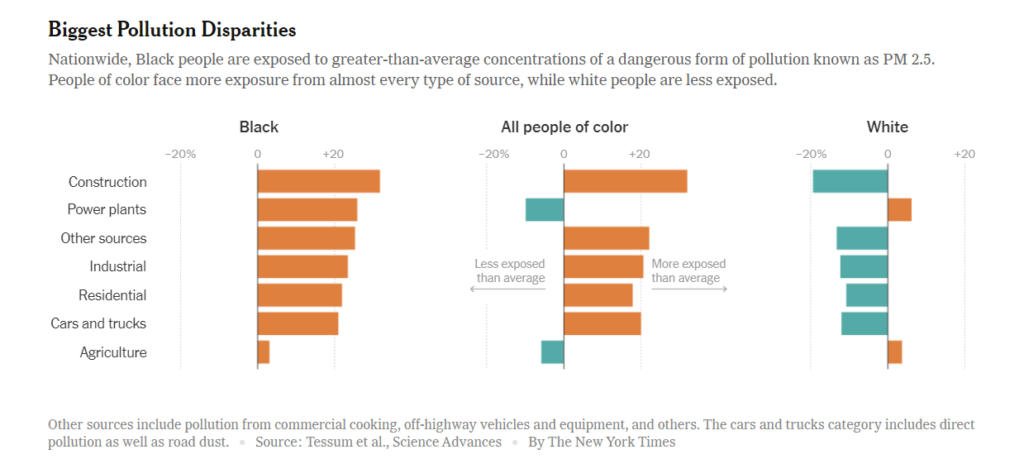

Tessum et al. (2021) found that across seven different forms of industrial pollution, Black people have higher-than-average exposure to all seven. People of color as a whole have higher-than-average exposure to five of the seven, and White people have slightly-higher-than-average exposure to two. The New York Times did a story on this study and illustrated the results with this graph:

To make matters worse, poor Black neighborhoods are much less likely to have a healthy tree cover, which can help filter out many kinds of pollutants (Locke et al., 2021) and reduce summer temperatures by as much as ten degrees. This will become increasingly important as global temperatures continue to rise.

Here’s another way of documenting the unfair environmental burden placed on people of color in the U.S. According to Tessum et al. (2019), there is a “pollution inequity” in this country. When you measure the air pollution people create through personal use (electricity, food, goods, information and entertainment, services, shelter, and transportation), White people produce more air pollution because they consume more goods and services, on average. But because pollution is disproportionately directed away from White neighborhoods and toward neighborhoods of color, White people experience less pollution themselves, on average. Black and Latinx people don’t produce as much pollution, on average, as White people, but they deal with significantly more than their fair share of it.

Sociologists Louise Seamster and Danielle Purifoy (2020) go so far as to say that environmental racism makes nice, White neighborhoods possible. When well-to-do White people say Not In My Back Yard, what they really mean is, “Go dump my pollution somewhere where the residents can’t say no.”

Law Enforcement

Race has been a huge factor in law enforcement throughout U.S. history. With the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement following the murder of Trayvon Martin in 2012, it has become even more salient. If you haven’t read it already, Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow provides an excellent history of race and law enforcement over the last 150 years. Here is a quick look at the big picture.

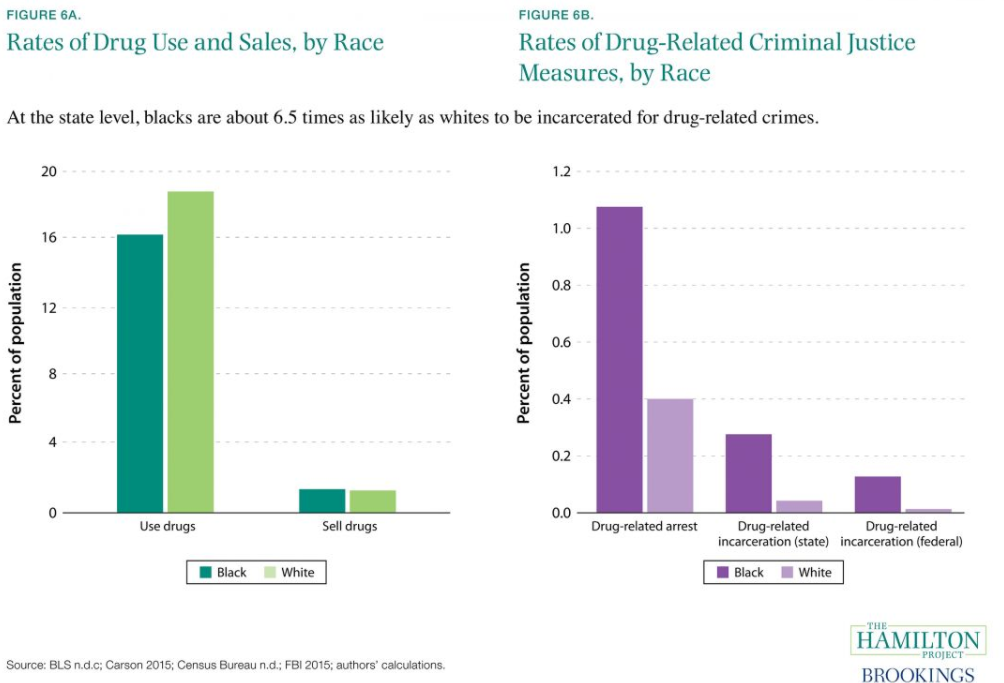

Murder and other violent crimes rose in the ‘70s and ‘80s and peaked in the early ‘90s. (There are 158 theories about that. Take your pick.) You would expect an increase in crime to lead to an increase in incarceration, but incarceration shot up beyond all reason. Young Black men were particular targets, especially for illegal drug use. Racial/ethnic differences in drug use are small. But racial/ethnic differences in incarceration for drug use are large. Why the disparity?

Part of the reason is that police officers have a lot of discretion in carrying out their responsibilities. Whether someone gets pulled over. Gets a ticket. Whether the car gets searched. Whether someone gets a warning, gets fined, or gets arrested.

Studies of stop and frisk in New York City found that Black and Latino young men were far more likely to be stopped and frisked than White young men—but White young men were far more likely to have drugs or illegal weapons when they were stopped. Why? White young men were stopped when they did something suspicious; Black and Brown young men were stopped whether they were doing something suspicious or not.

After an arrestee is taken in, prosecutors have similar discretion. Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus Vance, Jr., authorized a study of his office to see whether prosecutors were treating suspects differently by race. They were. Relative to White and Asian suspects charged with identical offenses, Black and Latinx suspects were less likely to have their cases dismissed, less likely to be offered bail, less likely to be offered plea bargains that avoided jail time, and more likely to be given a prison sentence at the end of their trial.

In 2020, the Criminal Justice Policy Program of Harvard Law School did a similar study

I’m not saying that people shouldn’t be held accountable for their actions. I believe they should. But I don’t think White people should receive more lenient treatment while people of color get the book thrown at them. Surely we can all agree on that.

These are just a few of the realities of racialization. Chris Hayes of MSNBC says that Americans of color constitute a colony within a nation. Imagine a Global South nation invaded and occupied by a colonizing power—except this colony is inside the occupying nation itself. Like all colonies, it is under-resourced and over-policed. And, I would add, the vast majority of those in the dominant group are perfectly fine with it. They’re so accustomed to it that they don’t notice, or they have learned all the racist ideology they need to justify it.

This is what theologian James Cone had in mind when he wrote this in Black Theology and Black Power in 1969:

I am not prepared to talk seriously with a man who essentially says, “I sit on a man’s back, choking him and making him carry me, and yet assure myself and others that I am very sorry for him and wish to lighten his load by all possible means—except by getting off his back.

The Bottom Line: This one’s from comedian Aamer Rahman: