If the racial views of most White Americans are, in fact, shaped by the context within which they live, then we need to understand that context.

Segregation now, segregation tomorrow . . .

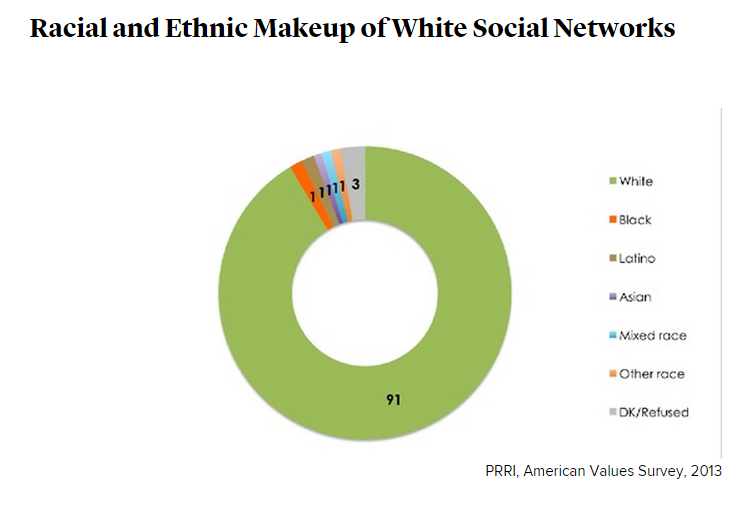

The most basic point to understand is that a significant majority of White Americans have spent their whole lives in racially segregated settings. Home, work, school, church, and neighborhood, those of us who are White often are isolated from people who are racially, ethnically, and culturally different. That’s no accident, of course. Governments at every level, banks, businesses, real estate companies, churches, and virtually every White-run enterprise have worked hard for centuries for precisely this result. White Americans, therefore, experience more racial isolation than any other group in the U.S.

It’s safe to say that not that many White people have meaningful conversations about racial issues with their occasional acquaintances of color, meaning that nearly all White people talk about race almost exclusively with other White people. Sociologists Leslie Houts Picco and Joe Feagan (2007) asked university students to take notes of the things White people say about race in private, all-White places (when they are “backstage”). It is discouraging, but not surprising, to learn that private conversations are much more overtly racist than public conversations (the “frontstage”). Many White people, then, are socialized–implicitly, at least–to present a non-racist front to the world while expressing racist attitudes and beliefs to other White people in private. They learn that racism is OK as long as it’s kept backstage. Racial segregation creates an echo chamber in which racist perspectives are largely unchallenged, depriving many White people of an opportunity to consider other views.

“I keep a lot of African American friends — some of my dearest friends — but when we hang out at the brew house, we don’t talk about these issues. A lot of residents are going, ‘Damn, I never realized my friends felt that way or had these experiences.’ ” —Ferguson, Missouri mayor James Knowles III, in the wake of the protests following Michael Brown’s death

Equal opportunity + unequal outcomes = something’s wrong with those people

Another very important component of the racial views of many White people is the belief that there is equal opportunity in this country for everyone, regardless of background, a conviction rooted deeply in the idea of the American Dream. Of course, many Americans do move up the ladder, at least a rung or two, and sometimes all the way to the top. Unfortunately, they are more the exception than the rule. In this country, even more than in many others, wealth begets wealth. Intergenerational mobility is lower than many Americans believe (and has been for some time), and the consequences of that immobility have grown as the gap between the haves and the have-nots has increased over the last forty years (Chetty et al., 2014).

Furthermore, as we see in the section on the Consequences of Stereotypes, people of color face continuing discrimination that makes it more difficult to get ahead in life, perpetuating inequality all the more.

In spite of the evidence, however, the White echo chamber asserts quite firmly that people of color have just as much chance to make it as White people. When you assume that there are no barriers to economic mobility, it’s easy to believe that those who don’t move up the ladder must be deficient in some way, responsible for their own stagnant status.

Sociologists Michael Emerson and Christian Smith (2000) interviewed White evangelical Christians and found that they (like most other White Americans) do not believe that either history or discrimination can explain racialization (on-going racial inequality). Neither do most of them believe that people of color are genetically inferior to Whites, rejecting that idea as old-fashioned. As a result, and almost by default, they conclude that contemporary inequality stems from the inferiority of Black culture and from the fact that Black people are lazier than White people. (Almost all the White interviewees in this study focused on Black people specifically, rather than on people of color more generally.)

Most important of all, many White people don’t see the racism in this way of thinking. They believe they are merely drawing a logical conclusion from these “facts”:

- The playing field is level.

- But some people aren’t doing as well as others.

- Therefore, they must be to blame, either individually or as a group.

Everything else flows from there. Do some people claim that discrimination still exists? They are “playing the race card.” Perhaps they are “professional agitators” who travel to places where everybody was getting along just fine before they started to rile things up. (Which is exactly what I heard about Dr. King when I was a child in the ’60s.) This is one of the reasons that many people dismiss any talk of racism as political correctness (a liberal fallacy) or critical race theory (mischaracterized as Marxist or unpatriotic or both).

This line of thinking is in no way a dispassionate analysis. There is an energy, a frustration, an anger, about race among many (though not all) White Americans. The interviews with White evangelicals in Emerson and Smith’s Divided by Faith are filled with this frustration. One example: “There are a lot of people just sitting back on their butts, saying because of circumstances in the past you owe me this and you owe me that. There’s a lot of resentment in the White community because of that . . .” (page 102).

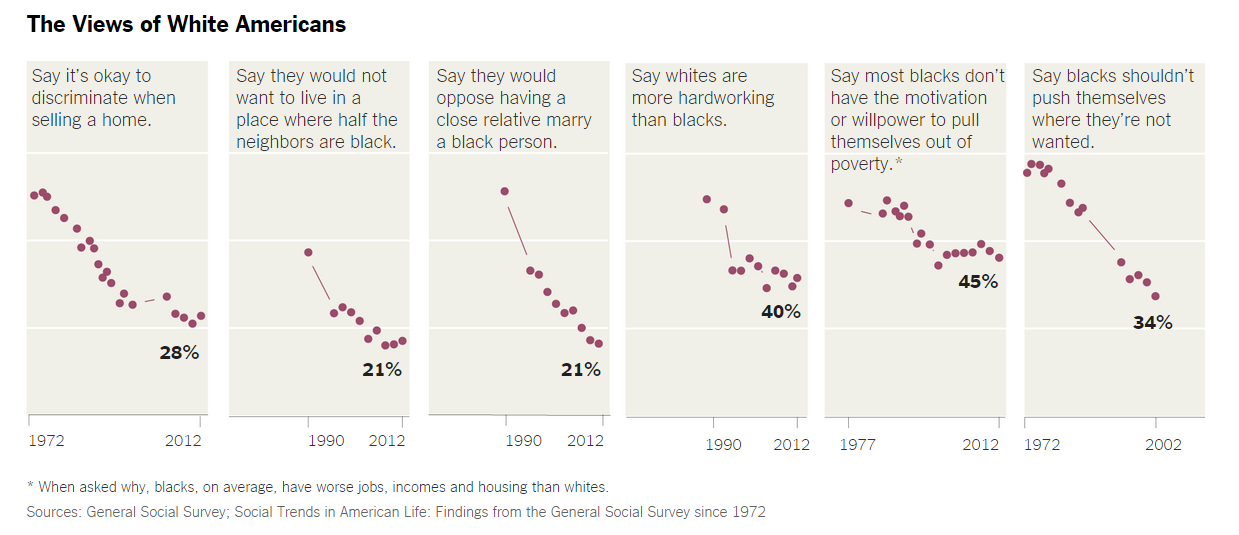

Of course, this is intimately and directly connected to stereotypes of people of color from the time of European colonization. Are overtly racist beliefs less common than they were a generation or two ago? Some are–but not those related to the belief that people of color get pretty much what they deserve in life.

Perhaps that is why many people are less likely to support legislation when it is described as promoting racial equity. Why offer a leg up to people if you believe they don’t deserve it?

“Racism is a changing ideology with the constant and rational purpose of perpetuating and justifying a social system that is racialized.” —-Emerson and Smith, Divided by Faith (2000)

Racism without Racists

Duke University Sociologist Eduardo Bonilla-Silva says that it’s important to remember that we can have Racism without Racists (2003). There are people who burn crosses or march with tiki torches or post racist comments on internet sites. But Bonilla-Silva says that, more often than not, they are beside the point. Racism persists because White people, on average, continue to have disproportionate access to power and resources (the vertical dimension of race) and because many White people believe that enduring inequities are not due to racism but to the deficiencies within people of color themselves .

Prof. Bonilla-Silva has identified four characteristics of the racial views of most White Americans:

- Abstract liberalism is using the language of the Civil Rights Movement to preserve the racial status quo. One example is using the concept of “equal opportunity” to argue against programs designed to make opportunity truly equal. “Reverse racism” is another, related, example–framing policies designed to counter persistent racism against people of color as racism against White people.

- Naturalization is a means of explaining racism as an inevitable consequence of human nature. Segregation isn’t pernicious, for example; it’s simply a result of people wanting to be with “their own kind.” Racialization is simply the way things are.

- Cultural racism is taking old stereotypes about the genetic inferiority of people of color and re-defining them in terms of their ostensible cultural inferiority, as we saw in the interviews from Divided by Faith.

- Minimization is down-playing racialization and its effects on people of color, asserting that neither historical nor contemporary discrimination affects anyone’s opportunities today.

We’re the victims now

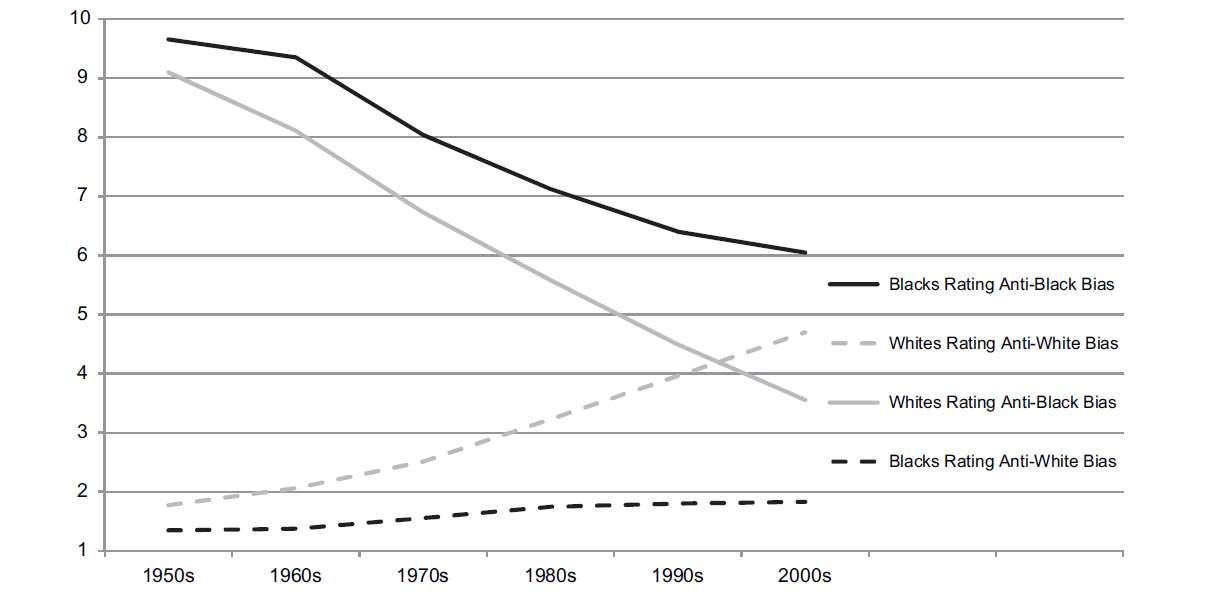

This way of thinking is why most White people believe that any attempt to reduce racialization is, by definition, an unfair attack on them. Look at this chart from Norton and Sommers (2011)

:

The two light-gray lines intersect in the mid-1990s, meaning that for nearly thirty years now, White people, on average, have thought that anti-White bias is a bigger problem in this country than anti-Black bias. And that perception keeps growing.

In a 2018 PRRI poll, just under half of young White men (and a somewhat smaller number of young White women) said that increasing diversity is a “harm” to White people. For them, this is no policy debate or abstract discussion. These people feel personally threatened, and many of them are vulnerable to those who want to exploit their fears.

Even if you buy into the false idea that life is a zero-sum game–that anyone else’s progress comes at my expense–there is no logical reason to be more concerned about the progress of people of color than the progress of other White people. If I don’t get the job, or the acceptance letter, does the race of the person who did really matter? Logically, no, it doesn’t. But psychologically, well, yes, it very well could.

So where does this sense of threat come from?

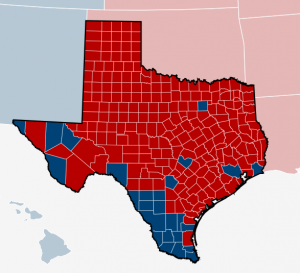

Robert Outten and his colleagues (2012) found that simply asking White people (American or Canadian) to read the projections of demographic change over the next 40 years left them feeling more angry toward and fearful of ethnic minority groups. Maureen Craig and Jennifer Richeson (2014) found, furthermore, that asking White people to read about upcoming demographic changes led many of them to take much more conserv ative stances on political issues. And not just immigration or Black Lives Matter. They became more conservative, too, in regard to the federal budget deficit and other topics less directly related to race. That political shift was mediated, in part, by concerns that White people will lose out as people of color increase in number. This is an important factor in the increasing political polarization of the country. Consider Texas, for example, which has gotten increasingly conservative during an era in which it has become more ethnically diverse. White, non-Hispanic, people now constitute just over 40% of the state, but those 40% vote together now in a way that keeps power in the hands of conservative White people.

ative stances on political issues. And not just immigration or Black Lives Matter. They became more conservative, too, in regard to the federal budget deficit and other topics less directly related to race. That political shift was mediated, in part, by concerns that White people will lose out as people of color increase in number. This is an important factor in the increasing political polarization of the country. Consider Texas, for example, which has gotten increasingly conservative during an era in which it has become more ethnically diverse. White, non-Hispanic, people now constitute just over 40% of the state, but those 40% vote together now in a way that keeps power in the hands of conservative White people.

The sense of threat leads, often, to anger. Not everyone is as angry as this woman, who is protesting a bus of children who crossed into the U.S. from Central America in 2014. There are many reasons people might oppose immigration, especially by those who come without papers. It’s the anger that is so telling, I think, that sense of threat, the fierce anxiety that a country she loves is slipping away and there is nothing she can do about it. That anger is everywhere these days, in politics and religion and education and every other corner of our national life. And we need to address it now, before it takes over completely.

The Bottom Line: Segregation from people of other backgrounds, the denial of racism past and present, on-going stereotypes of people of color, and rapidly-changing national demographics leave many White Americans feeling confused, angry, and threatened–enough fuel to keep racism going strong.