Perhaps you have noticed that this site uses the first person plural a lot. Ourselves. Who we are. There are a couple of reasons for that. One is that, like it or not, we’re all in this together. Race in America has changed over the centuries, but it hasn’t yet diminished. E Pluribus Unum is more hope than reality, even today. Especially today.

The second reason may be even more important than the first. Our language about social groups usually fits the us vs. them mentality we often decry. There are differences, of course–some deep and meaningful, others less so. But the more I study “intergroup relations,” the more I realize that we are studying the situations the groups are in more than we are studying the groups themselves. There’s nothing inevitable about the perspectives of either dominant or subordinate groups; those perspectives arise as a result of life experiences. It’s the different experiences that yield the different perspectives. If I’d had a different set of life experiences, I’d likely have a different set of perspectives, too.

Please read this section–Ourselves: Who We Are–with curiosity, self-reflection, and empathy. Some of our frustration about racial issues stems from the seeming irrationality of others’ views: Where would they get an idea like that? In our “what planet are they from?” moments, we ask this question rhetorically, to make our own points and express our own aggravations. As you read about The View from Above (perspectives of most dominant group members) and The View from Below (perspectives of most subordinate group members), try asking that question sincerely. Where would they get an idea like that? usually has an answer that can help us understand, even if we don’t agree.

Simultaneously, we have to be mindful that “liberty and justice for all” cannot merely be honored in the breach. When people believe or say or do things that diminish others, we must reject artificial equivalencies and put ourselves firmly on the side of those being diminished. As a rule, we needn’t demonize someone in order to challenge their racism. That’s both the ethical thing to do and, generally, more productive.

When dealing with individual people, the nature of the relationship matters, too, of course. As a professor, the way I respond to a student who has just said something racist is different from the way I respond to a colleague. When talking with students, I’m the one with most of the power, and I need to be careful not to abuse it in any way. Even with colleagues, I have to consider levels of informal power. As a senior White male faculty member, I know I have informal power even when I don’t feel like it.

With high-level administrators, where I have less power than they, while I want to be respectful, I have an obligation to speak plainly, especially when others are being harmed.

With high-level administrators, where I have less power than they, while I want to be respectful, I have an obligation to speak plainly, especially when others are being harmed.

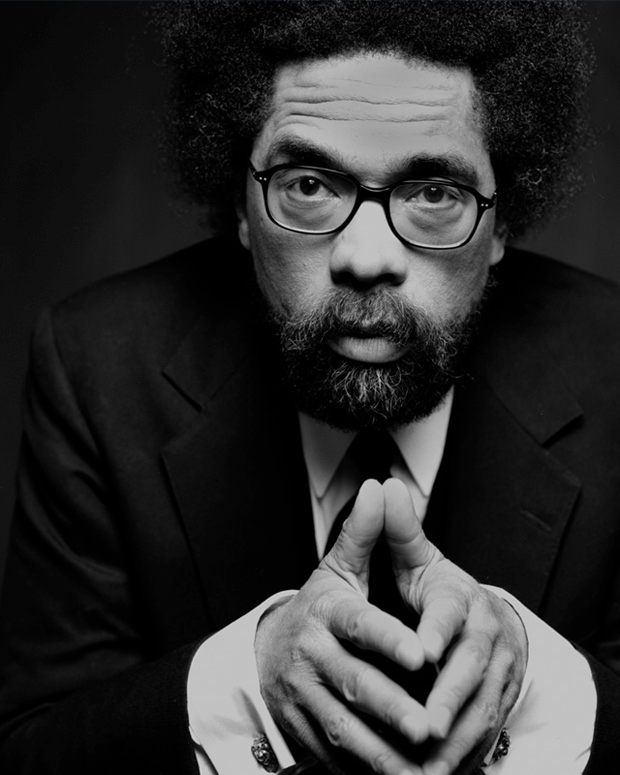

Respect, care, and truth, and all in the service of justice, because, after all, as Prof. Cornel West has taught us, “justice is what love looks like in public.”