I attend my neighborhood church here in Holland, Michigan. Of course, this being Holland, there are lots of neighborhood churches. One of my colleagues says, “I don’t attend my neighborhood church. I attend the one around the corner.”

Our church was founded in 1896, partly because the city was growing and new streets were being added, but mostly because the founders left a church that, under the leadership of second-generation Dutch immigrants, began conducting worship services in English. Some around here joke that it’s helpful to speak Dutch so that you can talk to God in God’s native language.

Ours was a church for immigrants, and for the children of immigrants who preferred the old ways.

But Americanization is awfully powerful, and the transition to English services began just a couple of decades later. Soon they were down to one Sunday evening Dutch-language service each month, and even that ended in 1936.

The first Mexican-American family moved onto our street 34 years later, in 1970, greeted warmly, I am happy to say, by Mrs. Van Zoeren next door, bringing a plate of cookies. By 2000, there were as many Latino residents in our census district as there were non-Hispanic Whites. But not in the church. Moving into a church is much harder than moving into a neighborhood. Our church is more diverse than before, but we don’t yet meet the sociological definition of a multicultural church, one in which no one ethnic group makes up more than 80% of the congregation.

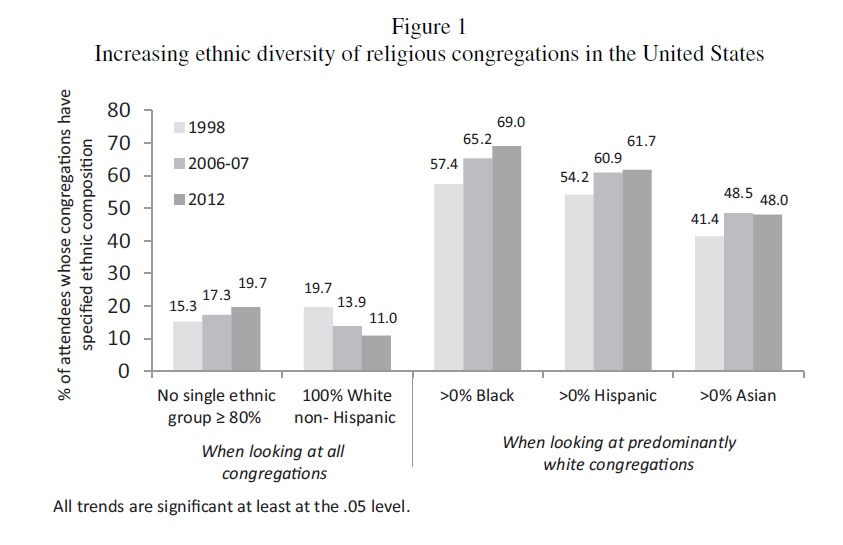

It’s a pretty loose standard, I think, but one that more U.S. congregations are meeting–nearly one in five, as of 2012. Roman Catholics have more diverse congregations than Protestants, for a variety of reasons, but small steps are happening across the religious landscape.

Sociologist George Yancey (2003) has studied multicultural churches, and finds that many of them don’t stay that way very long. Some are in transition, along with their neighborhood, from one racial group to another. Some find the effort too strenuous. In a culture in which Protestants, at least, tend to look for just the right church, one in which they are the most “comfortable,” being in the minority at church is tough.

Based on his research, Prof. Yancey says that there are seven principles that successful multiracial churches follow. Not every church follows each principle, but the bulk of multiracial churches follow the bulk of them. With just a touch of translation, they work pretty well for all kinds of institutions, I think.

1. Inclusive Worship

Prof. Yancey writes, “How we worship can be an important way to symbolize acceptance. An inclusive worship style communicates to visitors of different races that they and their culture are respected.” This is similar, clearly, to the “A” in Beverly Daniel Tatum’s ABCs of inclusion–affirm identity. Of course, the idea is to symbolize acceptance in a variety of settings, not just worship. For communities of faith, that would include education classes, youth activities, and other such activities. For a school, it would mean using a curriculum that included information about all the groups represented in the student body. I’m sure you can identity what it would mean for your organization.

2. Diverse Leadership

Again, reminiscent of Tatum’s ABCs, Prof. Yancey points out that seeing people in leadership from your ethnic group is important, especially for “racial minorities who historically have received a lack of respect for their opinions and perspectives.”

3. An Overarching Goal

“Surprisingly,” Prof. Yancey writes, “very few of the churches in the study made being multiracial a primary focus of their church. Rather, multiracial churches tended to have a goal that was aided by the fact that the church was multiracial.” This is an important point, I think, especially for those of us who are committed to racial justice. The simple truth is that most people won’t find the justice argument as compelling as we do. In the absence of an intrinsic desire to do the right thing, most people are going to need an extrinsic reason to do it.

Fortunately, as we saw in the section on The Benefits of a Diverse Environment, there are plenty of extrinsic reasons for racial justice. You’ll have to make the case, of course, because it won’t be intuitively apparent to very many people, but you can do that. Arin Reeves–an attorney, a sociologist, and the president of Nextions, a consulting firm–says in an article in Chicago Lawyer Magazine, “Know your ‘why’ and the ‘how’ will follow.”

That’s a fair bit more complicated than it sounds, but it’s excellent advice for those who want to get others involved in the work for racial justice.

4. Intentionality

There is a myth in this country that progress happens naturally, over time, and that if we just sit back and wait things will get better. For some reason, that myth is especially strong among many White people when they think about racial progress. People sometimes are annoyed with talk of racial justice because they don’t like the implications, but sometimes they simply don’t think the effort is necessary. Why work for change when you can wait for change? Prof. Yancey says just the opposite: “It takes work to create and sustain multiracial churches. Their development does not just happen accidentally. . . . Intentionality is the attitude that one is not going to just allow a multiracial atmosphere to develop but is going to take deliberate steps to produce that atmosphere.”

5. Personal Skills

There are few jobs, I think, that require as many different skill sets as leading a local congregation–public speaking, administration, counseling, fund-raising, planning, etc. Prof. Yancey says that the needs of a multiracial congregation require even more skills of church leaders: “sensitivity to different needs, patience, the ability to empower others and the ability to relate to those of different races.” Of course, it is important for congregants to develop those skills, too, perhaps relying on their own faith tradition to frame these skills in terms of the virtues their tradition prizes.

6. Location

Many multiracial congregations are located in multiracial neighborhoods, providing a context that supports their ministry. (Of course, there are lots of monoracial churches in multiracial neighborhoods, too.) In other kinds of organizations, the physical location may not matter quite so much, but the social location most certainly does. Developing an array of multiracial social networks is the functional equivalent of being in a multiracial neighborhood, and that’s something any organization can endeavor to do.

7. Adaptability

Life in any organization requires adapting to the preferences and personalities of other people. It also requires adapting to changing landscapes as things evolve. Multiracial churches require an even greater capacity to adapt to people and to change. Prof. Yancey points out that those who have been in the organization longer will need to steel themselves for more changes than they probably anticipated. That requires patience and courage, along with a capacity to keep the larger goals in mind.

That’s true for any faith tradition, of course. A Muslim friend of mine tells me that his mosque, mostly second- and third-generation Syrian- and Lebanese-Americans, has had to adapt in a number of ways to a recent influx of Iraqi immigrants. They share the Shi’a tradition, and the Arabic language, but with different emphases and different practices. Everyone has had to give up things that are important to them in order to worship together in one community.

Of course, Prof. Yancey points out, these are general principles that can be implemented in a variety of ways. How best to do that? “Be yourself,” he says. Find ways to be true to your organization’s character and values so that working for racial justice is authentic to who you are and who you want to be.

You might find something useful for your organization in these specific suggestions for promoting economic justice from The Othering & Belonging Institute at UC Berkeley. They cover quite a few different types of organizations.

Prof. Yancey’s book is, in effect, a compelling argument for affirmative action–being intentional about promoting racial justice. But he never used that term, and for good reason. Most White people oppose affirmative action, and if he had framed his arguments in that way, his book would have gotten a lot less attention.

Affirmative action h as been mis-defined, too often, as setting arbitrary quotas, or bypassing qualified White candidates in favor of unqualified people of color. Quotas are illegal, as it turns out, and the tales of hiring unqualified people are more urban myth than anything else. Most of time, affirmative action looks like Prof. Yancey’s seven principles. And, frankly, lots of people who say they don’t like affirmative action are using them. The Republican Party platform of 2012 took a stand against affirmative action, calling it “preferences, quotas, and set-asides” (page 9). But that same year they began a program of affirmative action themselves, scouring the country for women and people of color to run for office, building up affinity groups for minority Republicans, and making an effort to appear, and to become, more inclusive. Prof. Yancey’s principles work, whatever you want to call them, and whatever you think of affirmative action.

as been mis-defined, too often, as setting arbitrary quotas, or bypassing qualified White candidates in favor of unqualified people of color. Quotas are illegal, as it turns out, and the tales of hiring unqualified people are more urban myth than anything else. Most of time, affirmative action looks like Prof. Yancey’s seven principles. And, frankly, lots of people who say they don’t like affirmative action are using them. The Republican Party platform of 2012 took a stand against affirmative action, calling it “preferences, quotas, and set-asides” (page 9). But that same year they began a program of affirmative action themselves, scouring the country for women and people of color to run for office, building up affinity groups for minority Republicans, and making an effort to appear, and to become, more inclusive. Prof. Yancey’s principles work, whatever you want to call them, and whatever you think of affirmative action.

One final point. Inclusion initiatives need to be monitored well, and they need to be assessed for their efficacy. Kalev, Dobbin, and Kelly (2006) studied the employment practices of 708 private-sector companies from 1971 – 2002, comparing the results of various types of inclusion initiatives. They found that diversity training programs weren’t very good at improving the promotion of women and people of color into management positions. Mentoring and networking programs were a little more effective. But if you want to see real results, you have to identify specific people who are responsible for making things happen. Broad statements of encouragement won’t have much impact. Specific plans with specific people to implement them are much more likely to make a difference.

The Bottom Line: Working for racial justice in your organization requires changing the way you do things, eliminating barriers to full participation, and holding yourself accountable for the results.