Some years back, I was meeting with a student group (all White, as I recall) on the topic of becoming antiracist. I mentioned that college is an excellent time to branch out and get to know people from a variety of backgrounds. One young man was visibly distressed by that statement. He shot his hand in the air and said, sarcastically, “Well what am I supposed to do? Walk around Scott Hall (which houses the Phelps Scholars Program, a multiracial group of students in a living-learning diversity program) and ask, ‘Will you be my friend?’ “

I found his response, and the fact that he was so emotional about it, to be telling. Many White people are so deeply embedded in their White social networks that they simply can’t fathom that there is anything they can—or should—do about it. The very idea that they could break out of their isolation and segregation seems so ludicrous that anyone who suggests it deserves to be treated with contempt.

That young man isn’t alone. I regularly get questions from White people about specific, practical things they can do to be antiracist. Often there’s a sense that they are completely at a loss. They’ve thought about it, but nothing has come to mind; they simply don’t know where to start.

Wherever you are, whoever you are, you can start by reading books, listening to podcasts, following antiracist activists on social media, and identifying groups in your community working on behalf of marginalized people. Those are all good things. You should do them. Often, however, they are add-ons—things you add to your life without changing anything else. More effective, I think, is to be intentional about embedding antiracism into your daily living.

Here’s an analogy. A lot of people recycle. But for many people, recycling is their one and only contribution to caring for the environment. They drive large cars and live in large homes, often miles from work and other regular destinations. They don’t reduce the number of things they buy, or the number of single-use products they consume. In fact, they might even feel good about themselves if there are a lot of items in their recycling container each week. However, it would be much, much better if they cut back on the number of things they use, reduced their energy consumption, lived in a place where they didn’t have to drive long distances, etc. It would be better if they would embed environmentalism into the choices they make in their daily living. They wouldn’t have to do an extra thing or two to be environmentally responsible. It would be “baked in” to their ordinary, everyday lives.

Same thing with being antiracist. We can—and should—do some extra things to fight racism. But it’s even better if we embed antiracism into the choices we make in our daily living. There are a handful of decisions we can make, especially if we are White, to embed antiracism into the choices we make in our daily living. We wouldn’t have to do an extra thing or two to be antiracist. It would be “baked in” to our ordinary, everyday lives.

I’d like to address just three questions that can help you do that:

- Where will you live?

- Where will you worship?

- How will you raise your kids?

If you’re White and you go with the cultural flow in making those decisions, you’ll end up surrounded by other White people living a hyper-segregated life. But counter-cultural decisions—antiracist decisions—will enable you to have an antiracist effect as you go about your regular routine.

Where will you live?

This is, in most cases, the most important of these three questions.

I gave a quick overview of racial segregation in the U.S. in the post called Realities of Racism: Living with Racialization. The bottom line is that residential segregation in this country is very high—higher in many places than at any point in the last several decades. Where we live is so central to our lives that residential segregation is the “linchpin” for many other kinds of segregation, too. It matters.

Segregation is driven largely by White people’s preferences for neighborhoods in which Whites are a significant majority. The belief that “good” neighborhoods have White residents and “bad” neighborhoods have residents of color runs deep. In fact, many White people use the term “good neighborhood” to signal that it is White.

Maria Krysan and her colleagues (2009) did a terrific study in which they showed a videos of fifteen different neighborhoods to people in the Chicago and Detroit metropolitan areas. Each participant watched just one video. There were five different types of neighborhoods (from “lower working class” to “upper class”), each of which was shown with three different types of residents (all-White, all-Black, and half-White/half-Black). Participants were asked whether they would want to live in the neighborhood they observed. Not surprisingly, the wealthier neighborhoods got the most positive ratings. But above and beyond that, White participants also preferred the neighborhoods with White residents over the Black and integrated neighborhoods. Black respondents preferred integrated neighborhoods overall. The next time someone tries to tell you that residential segregation exists because “birds of a feather flock together,” make sure they understand that’s true mostly of the white birds. (See Krysan and Bader (2007) for more on that.)

My point is that if you’re White, you likely will need to overcome some resistance to the idea of moving into an integrated neighborhood. It may take a bit of extra effort, but it can be done.

Political scientist Ryan Enos calls this a “liberal dilemma, where things that liberals value collectively are not things that liberals are individually willing to pay the costs to achieve.” When people of color begin to move into a well-to-do White neighborhood, liberal Whites who say they endorse integration have to weigh their values against their fears, fears that their home might decline in value or their children’s school will become less attractive to other White people who might consider moving into the neighborhood. If they leave the neighborhood, they’re contributing to segregation regardless of their motivation.

Fortunately, that’s not a decision people have to make independently—they can work with others in their community to support integration. Oak Park, Illinois, just outside of Chicago, is pretty integrated by U.S. standards, and they work very hard to keep it that way. They do their best to ensure that potential renters and buyers see apartments and homes across the city, particularly in neighborhoods where they would not be in the majority. Quite a few people, in turns out, end up selecting a place in an integrated neighborhood, once they get to know it a bit better. Maria Krysan calls those neighborhoods “blind spots” in a community—good places to live that many people won’t consider unless they learn more about them. But not many communities make those blind spots visible. The director of the program in Oak Park calculates that without their program, most neighborhoods would become racially segregated in just five years.

You probably don’t live in Oak Park, so you’re going to have to seek out integrated neighborhoods on your own. Do some research, drive around a bit, find a good (antiracist!) realtor, and you likely will find an opportunity to get out of the White bubble most White people believe is inescapable.

But please, please, please remember that when you move into a neighborhood in which you may be in the minority, you’re doing it for yourself, not for the neighborhood. I’m not saying you don’t have a contribution to make. But you’ll still be the primary beneficiary. The opportunity to get to know people from other backgrounds will be good for you in many ways. It will enhance your knowledge of other people, reduce your anxiety about intergroup contact, and increase your empathy and ability to take the perspective of others (Pettigrew and Tropp, 2008). It will raise your level of trust in others (Schmid, Ramiah, and Hewstone, 2014). And it will reduce your level of implicit bias (Shook and Fazio, 2008). In a nation as racialized as ours, that’s a pretty impressive pay-off.

Where will you worship?

When I was a kid, I spent a whole lot of time at church. We were a three-times-a-week family. I remember lots of singing in the children’s classes, and one of the many songs we sang was a little ditty called Deep and Wide.

Deep and wide.

Deep and wide.

There’s a fountain flowing deep and wide.

Deep and wide.

Deep and wide.

There’s a fountain flowing deep and wide.

And that’s it. That’s all there is to it. Deep and Wide doesn’t have the theological import of Jesus Loves Me. It doesn’t teach a Bible story like Only a Boy Named David or Zacchaeus Was a Wee Little Man. So what does a four-year-old learn from singing Deep and Wide? What can the rest of us learn?

The answer is found in the most important word in the song. It’s not deep. But it’s not wide, either. It’s and. There’s a fountain flowing deep and wide. Not deep or wide. Not deep but wide. Certainly not deep versus wide. A fountain flowing deep and wide.

For people of faith, this fountain represents the depth and breadth of God’s love for us. God’s love is deep and wide because God is deep and wide. Scripture tells us we were created in the image of God, suggesting that we, too, were meant to be both deep and wide. In the beautiful imagery of Psalms 1, to be deep and wide is to be like a tree, rooted deep by streams of flowing water and branching wide to offer our fruits in their season.

But that’s not how most of the White American church works. Deeply embedded in colonialism and conquest, the church played an integral role in creating a racialized society and developing the rationale that justified it. Sadly, it still is. You don’t have to take my word for it. William J. Barber, Austin Channing Brown, Mark Charles, Kaitlyn B. Curtice, Soong-Chan Rah, Lisa Sharon Harper, Robert Chao Romero, Jemar Tisby, Chanequa Walker-Barnes, Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove, and many, many others explain it better than I.

The point is, if you are a person of faith, Christian or otherwise, you need to be able to see the ways in which many of your faith leaders and their congregations have cozied up to racism and have become comfortable with segregation, inequality, and the ideology by which they are perpetuated. (The authors listed in the previous paragraph can help you do that.) Then you need to find other leaders and congregations in your tradition that are stripping racism out of their beliefs and practices and working toward being antiracist. People who believe God is deep and wide. People who want to become deep and wide themselves.

For example, if you’re looking for a home congregation, someone is bound to recommend one where you can feel “comfortable.” When they do, dig a little deeper. Odds are, when they say “comfortable,” they mean “everybody there looks and thinks just like we do, and we keep everyone else out.” Tell them no. Faith should be deep and wide because God is deep and wide, that you’re most comfortable in a congregation that’s deep and wide, and you will be looking for one of those.

It requires practice to see with new eyes, to hear with new ears, to discern and to dream according to higher principles and nobler values. But isn’t that at the heart of what faith is all about?

How will you raise your kids?

This is a huge topic all by itself, of course, but let me share with you three excellent resources to get things going, at least.

Resource #1:

In an essay posted on the website for a group called Integrated Schools: Families Choosing Integration, a White mother identified only as “Anna” explains that she chose to send her daughter to their local public school where only 5% of the students are White. Why? Because of the importance of providing children with an opportunity to learn in a diverse environment.

“Because unless I am intentionally placing my children in diverse settings, both socio-economically and racially, unless I am intentionally acknowledging and addressing the issues of school segregation that have divided this great city, I will raise a racist. I won’t mean to. But intentions are no longer enough. Unless I am forcibly putting her out in to the world, confident in her resilience, humanity, and grit, I will keep her cloistered and separate from the truth of what it really means to be an equal among equals.”

“I will raise a racist.” You may think that sounds harsh, or extreme, over exaggerated, but it’s actually spot-on. I don’t think the author means she will raise a neo-Nazi or a skinhead or a Proud Boy, although that’s a possibility. She’s saying that in the kind of segregated contexts in which most White Americans live, it’s almost impossible not to be racist, at least implicitly. Children will look around at their neighborhood, their friends, and their family’s social network, and make inferences both about the people who are there and the people who aren’t. My parents only want to be friends with other White people. My family chose to live in a place with no people of color. My school is great, and the teachers and the students are all White. Kids make inferences all the time from the things they see and hear. They pick up on all kinds of social norms without anyone ever having to say anything aloud. Why would the presumed superiority of White people and White places be any different?

Nikole Hannah-Jones, who has written extensively about school segregation, among other things, points out that sometimes all the bells and whistles of wealthy schools (or most any other characteristic they many possess) often are used as a non-racial way for White parents to justify selecting a White school for their children:

According to Ms. Hannah-Jones, “schools are segregated because white people want them that way.” But not all. There are those making different decisions in order to provide their children with a richer education and a better preparation for life.

Resource #2:

In the summer of 2021, the American Psychological Association published an excellent summary of key research studies on minimizing the effects of the smog of racism on children. The author, Kristen Weir, identifies a number of things parents, teachers, caregivers, and others need to know.

Ms. Weir points out, again, that when parents ignore race, kids will come to their own conclusions by observing the world around them. Most White three-year-olds play with other kids regardless of their skin color. Just one or two years later, those same White kids seek out other White kids to play with and develop segregated friend groups, even if the grown-ups never talk about it. Or, should I say, especially if the grown-ups never talk about it. Children of color don’t segregate themselves as much, suggesting that kids are responding not so much to differences of culture (the “horizontal dimension”) as to differences in status and standing (the “vertical dimension”). It’s not that kids want to play with other kids who are similar culturally; it’s that the kids who see themselves as “on top” want to play with other kids who are “on top” as well.

I saw this first-hand in my very first set of research studies in graduate school. I landed at the University of Florida in Gainesville in 1978—just five years after the Gainesville public schools desegregated. I worked with two professors in examining interracial relationships in the five middle schools in town. Three of the schools maintained the traditional patterns and procedures they had before desegregation, grouping children in classes according to test scores and grades which, in effect, organized the whole school day (not just the class periods) along those lines. There was very little interracial interaction among kids in those schools. Their cafeterias, for example, had tables with White kids and tables with Black kids and very few tables with both. Two other middle schools, however, did not put kids with different test scores into different classrooms, opting instead for classrooms where kids with a wide range of test scores learned together. They adopted interactive, activity-based learning strategies like the jigsaw technique that are more effective for children who don’t learn as well in traditional lecture-based classes. (The bonus? Kids who do well in traditional classrooms do well in more interactive environments, too.) Another important benefit: the students made friends both within and across racial lines. There were White tables in their Cafeterias, and Black tables, too, but far more tables that were integrated, as well (Damico, Bell-Nathaniel, and Green, 1981, 1982; Green, Adams, and Turner, 1988).

Interestingly, administrators in the traditional schools bemoaned the poor performance of many of their students of color and tut-tutted over their segregated cafeterias, but said, in effect, “Well, that’s the way the world is. There’s nothing we can do.” They created schools that decreased academic performance and increased segregation, but had no idea that they were reaping what they themselves had sown. It happens all the time in many different kinds of organizations.

In light of the very large number of segregated or racialized environments in which our children live, what should parents, teachers, and other adults tell kids about race?

Parents of color usually are more pro-active in talking with their kids about race, of course. They have to be. Children of color absorb the broader social messages about race just as White kids do. They realize early on that they are part of a subordinate, often stigmatized, group, and it can be difficult for them to grow up with a positive sense of their own identity. That’s why many of their parents do their best to counter the dominant narrative and teach their children that they—and their race/ethnicity as a whole—are beautiful, smart, and valuable. Family stories, for example, can teach a rich heritage and instill a sense of gratitude and pride. Many parents choose books, movies, and other media with positive, counter-cultural messages for kids. Unfortunately, they also have to let their kids know about the reality of bigotry and discrimination in order to prepare them to deal with it when, inevitably, it comes their way. The combination of these two messages—pride in heritage, preparation for hate—is associated with positive psychological and academic outcomes for kids later on.

Psychologists Diane Hughes, Celia Fisher, and Natasha Cabrera point out that, unlike parents of color, White parents are more likely to downplay race and racism in conversations with their kids, even when things like the murders of Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown, Jr. dominate the news. The research shows, however, that it’s better for White parents to talk with their kids about race and racism, preferably before a tragedy or crisis. Let kids know that people come from different cultures and backgrounds. We’re all human, to be sure, and share many things in common. But sometimes we express our humanity in different ways. And sometimes, people are mistreated because of their heritage. Such conversations help prevent White kids from assuming that the world is just and most people get what they deserve. And because White self-segregation begins at 4 or 5, parents, teachers, and other adults need to start early. Otherwise, as we’ve seen, kids absorb the messages of their surroundings and internalize the racism of our society.

Naturally, parents and teachers have to do their own work first, so they can be authentic with the children in their care, prepared to answer questions, and actively modelling inclusion. The other posts in this Getting Personal section can help with that.

Resource #3:

The Southern Poverty Law Center was established in 1971 “to ensure that the promise of the civil rights movement became a reality for all.” They have a resource for school teachers called Learning for Justice (formerly Teaching Tolerance). In 2019, Coshandra Dillard wrote an excellent essay in Learning for Justice with the title, “Five Ways to Avoid Whitewashing the Civil Rights Movement.” It’s great advice for anyone who loves and cares for kids, and it applies to many different race-related topics, not just the Civil Rights Movement. Here’s what she had to say:

- Educate for Empowerment. Information is never neutral and it never exists in isolation from other things we know. Talk to kids about race and racism in a way that helps them understand not just what’s going on, but what they can do about it—for example, how they can treat other people the way they’d like to be treated themselves.

- Know How to Talk about Race. Don’t wait for race to be “an issue” before saying anything. Be a learner yourself, be prepared, and be proactive.

- Capture the Unseen. One of the ironies of the Civil Rights Movement is that we tend to marginalize so many of the people who fought against marginalization. For example, we don’t know enough about the many, many women who often were the heart and soul of the movement. We don’t talk about the LGBTQ civil rights leaders or make the connections between the fight for civil rights and the many liberation movements that followed (for women, for gays, for the disabled, et al.).

- Resist Telling a Simple Story. The movement for civil rights was for all kinds of justice—economic justice, international peace, fair housing, good schools—not only for the desegregation of public facilities. Tell the whole story (in an age-appropriate way, of course) and help kids understand both the progress that was made and the work that still needs to be done.

- Connect to the Present. What are the justice issues we’re facing now? Whose rights are being questioned or violated? Connect contemporary news headlines with the struggles of the past to empower kids (see point number one) to make a difference today.

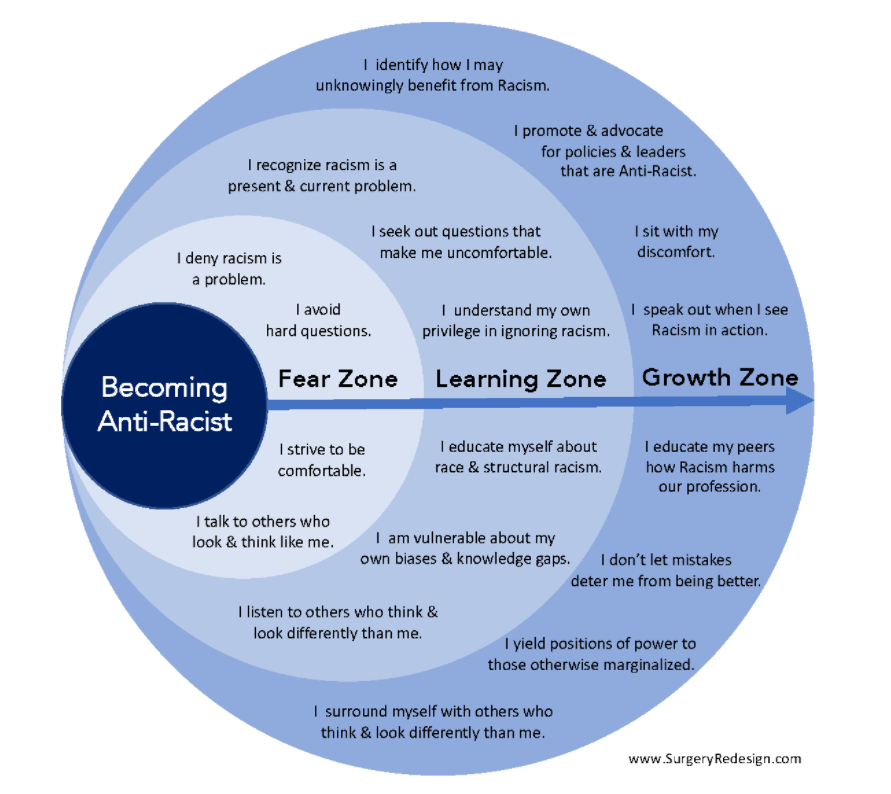

Of course, all this takes time, and you grow into it gradually. This graphic from the Washington University Milliken Department of Medicine can offer some insight into how far down the path you may have come, and some of the tasks ahead of you on the trail.

The Bottom Line: Sometimes being antiracist means adding new things to your life: community work, volunteer service, political initiatives, etc. Those things are great. It’s also good to embed antiracist principles into your daily living so that you make a difference just by getting up in the morning and living your life.