There’s been quite a bit written and discussed on this topic. The most common word people use to describe White people who are supportive of people of color is “ally.” (More broadly, the term can be used to describe any dominant group member who supports those in the corresponding subordinate group: feminist men, pro-LGBT straight people, non-Muslims who oppose Islamophobia, etc.) There’s concern that this term is too passive and that many who consider themselves allies are really more like sympathetic bystanders. But it’s the word most people have used, and I’m going to stick with it for now.

Whatever word we use, the concept is important. Many, many White people who say they’re against racism still cling to the benefits of being White. It happens all the time, again and again. Betsy Hodges, mayor of Minneapolis from 2014 – 2018 says that she regularly watched liberal White people block antiracist change in the city. You should read the entire article, but here’s a short excerpt:

“In Minneapolis, the white liberals I represented as a Council member and mayor were very supportive of summer jobs programs that benefited young people of color. I also saw them fight every proposal to fundamentally change how we provide education to those same young people. They applauded restoring funding for the rental assistance hotline. They also signed petitions and brought lawsuits against sweeping reform to zoning laws that would promote housing affordability and integration.”

What many people really want, in effect, is a kinder, gentler racism. So please don’t mistake your warm fuzzy feelings for allyship. You get no cookies, as they say, for tut-tutting about the Proud Boys. Psychologist Monnica T. Williams of the University of Ottawa says you’ll know you’re an ally if you meet these three fundamental criteria:

- Allyship is an act of support and not leadership.

- Allyship is a continuous behavior, not isolated acts.

- One’s allyship status is recognized by marginalized group members.

An ally, then, has some skin in the game—someone who’s willing to take risks on behalf of others. But an ally also accepts a supporting role. Those of us in dominant groups often are accustomed to being the leader, speaking out, offering our ideas, and having our way. Being in a supportive role, then, might not be natural for us, and it can take some time to make the adjustment. I think Dr. Williams’s third point, therefore, is critical—the status of ally is conferred by those on the margins, not those in the center. That’s the sign that you’re doing something right.

One very important step in learning to be an ally, then, is listening to those on the margins. Christena Cleveland, a social psychologist and public theologian, has a series of posts on how allies can listen well. It’s terrific. She says she experiences allyship from two different perspectives:

“As someone who identifies with both privileged (highly educated, upwardly-mobile) and oppressed (black, female) groups, I’ve experienced both ends of the privileged-oppressed spectrum. As a result, I’ve played the part of the privileged perpetrator of oppression as well as the oppressed target of oppression. And within the reconciliation context, I’ve often had to ask for grace and I’ve often had to give grace. These thoughts on listening well as a person of privilege are based on my experiences as a privileged person and an oppressed person.”

In her posts, Dr. Cleveland offers five things dominant people need to do when listening to marginalized people:

- Recognize that the rules are different for you.

- Solidarity first, collaborative problem-solving later.

- Communicate on their terms, not your own.

- Recognize the limitations of good intentions.

- Seek to understand and embrace anger.

That takes a lot of listening. How can we do it well? Ralina Joseph, professor of communication and director of the University of Washington Center for Communication, Difference, and Equity, says that listening isn’t enough–it has to be “radical listening.” Focus completely on the speaker. Learn to suppress your own thoughts. Make sure you signal to the speaker that you are listening carefully. Repeat back what you’ve heard to make sure you understand. Then act on what you’ve learned; use it to make a difference.

All great stuff, but not easy, and I’ve stumbled more than once. You might, too. But it’s not about us, not about our feelings or our inadequacies. It’s about the work, so when we mess up, we reflect for a bit, learn something we need to know, and head back into the game.

In an article entitled, “How to be a good ally in the fight for Black justice,” Demonte Alexander quotes an ally in San Antonio offering three components of allyship:

“Being an ally to me is about acting with and on behalf of those who do not share the same privileges as I. It’s about helping to amplify voices that are not my own and calling out discriminatory and racist behavior without fear. It’s about working in solidarity with the Black community in pursuit of achieving justice and creating equality.”

Let’s look at each of these components in turn:

First: Amplifying voices that are not my own. Who are you reading? Who are you quoting? Who are you recommending to others? Whose praises do you sing at work? Who do you bring into the converstion (with permission) when they are being overlooked? Who are you mentoring? Who are you welcoming?

Second: Calling out discriminatory and racist behavior. So, so, so much good advice on this. Here is one example. And another. And one more.

Psychologist Derald Wing Sue and his colleagues (2019) summarize all the ways to respond to racist acts into these four categories:

- Make the invisible visible. Call out racism when you see it. Ask for clarification. Reject the stereotype.

- Disarm the microaggression. Make sure people know you disagree. Describe what’s happening and why it’s racist. Redefine and redirect where the conversation was going.

- Educate the offender. Promote empathy. Appeal to shared values and beliefs. Distinguish between intent and impact.

- Seek external reinforcement or support. Report the offense, if it violates pertinent harassment rules. Offer to support the aggrieved, personally, perhaps, or through counseling or other sources of support. Offer to talk with the offender again.

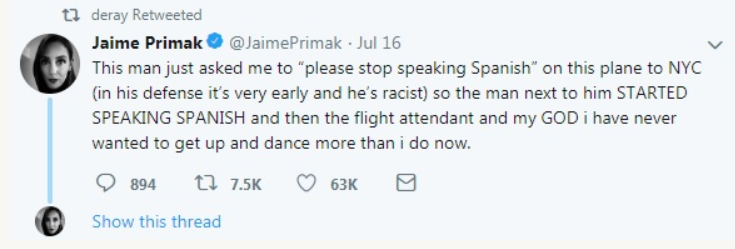

Sometimes a response can be simple:

And sometimes it needs to be more involved:

https://vimeo.com/192150862

Third: Working in solidarity with the Black community [and other marginalized groups, I would add] in pursuit of achieving justice and creating equality. There may be a whole new initiative you’d like to start. But odds are, people have already come together in your community to work on these issues. Ask around, search online; it won’t take long before you find a group to support with your time and/or money. Want some other ideas? Here are 103 of them. That should keep you busy and out of trouble for a while, at least.

The Bottom Line: We all have at least one dominant identity, so we all have an opportunity to be an ally to those who are marginalized. Like any behavior, it takes time and regular practice for allyship to become a habit. We have to learn to see the need and commit to offering our support.