Racial Progress

I am a social scientist, someone who believes that research, while imperfect, can help us go beyond our myths and presuppositions and better understand ourselves and our world. As the late psychotherapist Carl Rogers (1961) wrote, “the facts are always friendly,” meaning that even when the facts aren’t what we want them to be, we’re better off when we acknowledge reality than when we deny it. The social science research on race and racism helps us do that, to pull back the layers of misinformation and ideology and see what’s really going on.

I’m also a person of faith: more specifically, a Christian. Christians care about truth, too, just as researchers do. There are only Ten Commandments, after all, and one of them is an admonition against lying. Christian author and speaker Lisa Sharon Harper writes that Christians, in particular, should have the curiosity to seek the truth, the humility to listen to the truth, and the courage to speak the truth. We have a moral obligation to do our homework and get our facts straight. Like research, faith requires an honest accounting, a willingness to see things as they are.

Love of God and love of neighbor . . .

But faith also helps us see how things ought to be. As a Christian, my goal is to interpret the research on race and racism in light of the many biblical teachings about how people are called to live together in community and justice, the Hebrew concept of shalom. Shalom is a state of right relationships in which both a society and the individuals within it can flourish and thrive. Hugh Welchel of the Institute for Faith, Work, and Economics, says

[T]here is one forgotten concept that permeates the grand metanarrative of scripture. This is the idea of human flourishing captured in the Old Testament Hebrew concept of shalom. Most of our English Bibles translate the word “shalom” as “peace,” but this is far too weak an interpretation. Biblical scholars tell us that shalom signifies many things, including salvation, wholeness, integrity, soundness, community, connectedness (to others and God’s creation), righteousness, justice, and well-being (physical, psychological, and spiritual).

Anything less simply won’t do. There is no room for excuse or complacency. No looking away, no explaining away. We won’t get to shalom this side of heaven, but it is always the goal.

The two great commandments Jesus gave in Matthew 22 are pathways to shalom:

37Jesus replied: “‘Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind.’ 38This is the first and greatest commandment. 39 And the second is like it: ‘Love your neighbor as yourself.’ 40All the Law and the Prophets hang on these two commandments.”

Love of God and love of neighbor enable us to be who we are supposed to be, who we are called to be, who we are at our very best. Christians, then, must be clear-eyed about today’s realities while simultaneously moving toward the shalom that is our goal. Getting race right is an excellent example of living in the tension between where we are and where we ought to be, both individually and as a society. That’s why it’s at the very heart of the gospel.

. . . or not

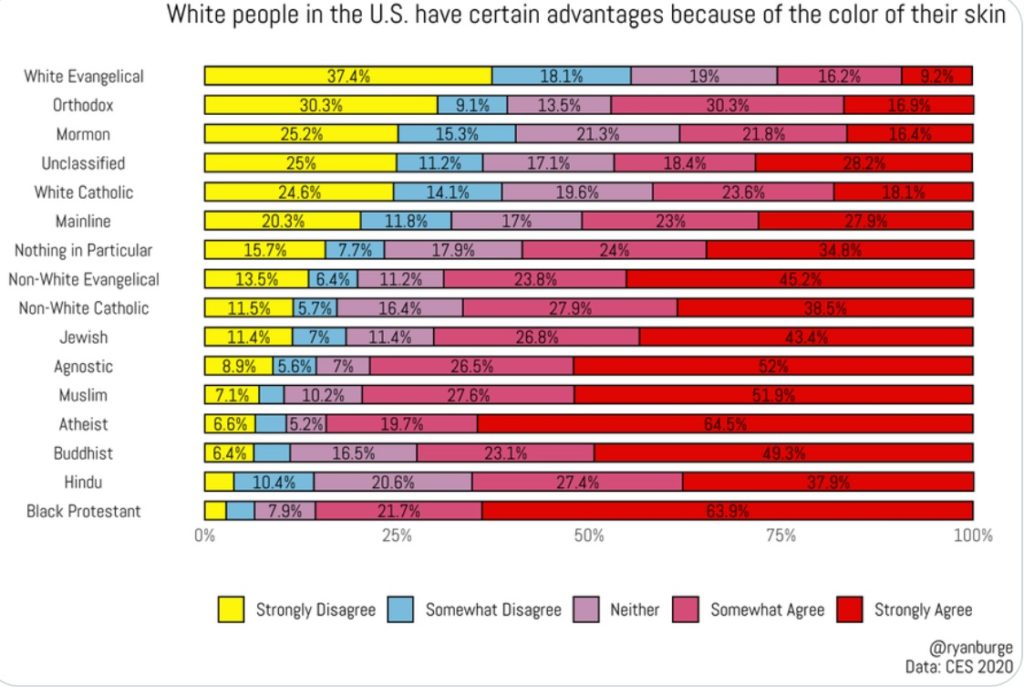

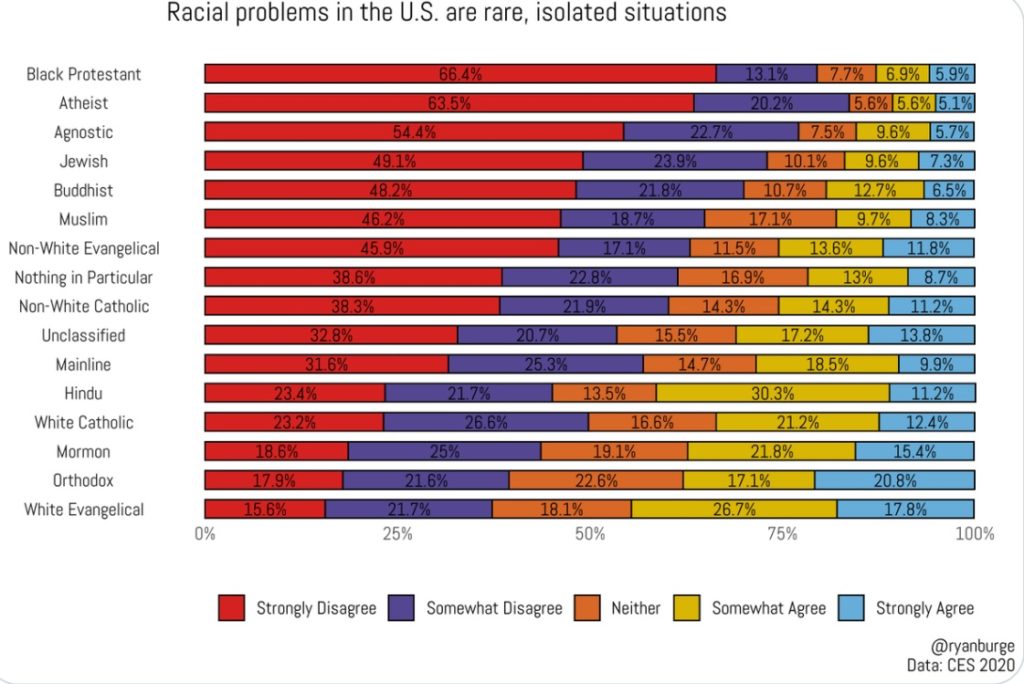

Unfortunately, when it comes to race, White American Christians are all over the map (Jones, R.P., 2020, especially Chapter 5; see also here and Figure 3.7 here). Many are deeply opposed to racism and its devastating effects on themselves and their neighbors. Others have decided that racism either isn’t a problem or isn’t relevant to their faith. A third group of Christians has absorbed the racist assumptions and perspectives of the broader society. They believe that God’s love is reserved for people like them, that people of other races, ethnicities, religions, or nationalities don’t fit the definition of ‘neighbor’ and therefore don’t have to be loved—indeed, don’t deserve to be loved.

posted on Twitter, January 17, 2022. Note that there are average differences

among groups, but significant variability within groups, too.

posted on Twitter, January 17, 2022. Again: average differences

between groups and a lot of variability within groups, too.

It can be stunning to realize that racism—and its denial—is rampant in the White U.S. church, but the fact is (the “friendly” fact, mind you) that the church has a long tradition of proclaiming a White Supremacist version of the gospel. It began in the early days of European colonization. Christian pastor and Native American activist Mark Charles has been teaching and writing for years about the “Doctrine of Discovery,” a series of 15th century papal bulls (official edicts from the pope) that blessed European colonization and gave Europeans permission to invade non-Christian nations, plunder anything of value, and enslave the people (Charles and Rah, 2019). The church hierarchy benefited directly from colonial exploitation. Just one example: the construction of St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome was funded, in part, by the looted Incan treasury conquistadores brought back to Spain (Scotti, 2006). And it wasn’t just the Catholic Church. After the Reformation, most Protestant denominations continued to endorse conquest and slavery outside of Europe. At the very least, they learned to live comfortably with it.

Racism as polytheistic idolatry

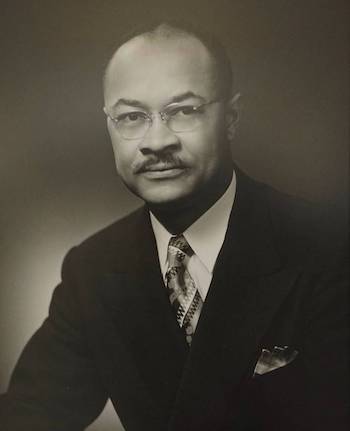

Dr. George Kelsey (1965), a Christian theologian and ethicist who taught and mentored Dr. King at Morehouse College, believed that White Supremacy in Christians went way beyond any acceptable level of cultural accommodation. He argued that racism was so incompatible with following Jesus that racist Christians are functioning polytheists:

“When the racist is also a Christian, which is often the case in America, he is frequently a polytheist. Historically, in polytheistic faiths, various gods have controlled various spheres of authority. Thus a Christian racist may think he lives under the requirements of the God of biblical faith in most areas of his life, but whenever matters of race impinge on his life, in every area so affected, the idol of race determines his attitude, decision, and action. . . . Polytheistic faith has been nowhere more evident than in that sizable group of Christians who take the position that racial traditions and practices in America are in no sense a religious matter. . . A probable explanation of this peculiar state of affairs is that modern Christianity and Christian civilization have domesticated racism so thoroughly that most Christians stand too close to assess it properly.“

Professor Kelsey called racism out for what it is: idolatry.

So did Rabbi Abraham Heschel. In a 1963 speech to a conference on Religion and Race in Chicago, he said, “Any god who is mine but not yours, any god concerned with me but not with you, is an idol.” (Emphases in the original text.) “Idol” is exactly the right word. When we say, “I will love my neighbors if they look like me,” we put our prejudice above God, as an idol. When we say, “I will love my neighbors if they are citizens of my country,” we put our patriotism above God, as an idol. When we decide to interpret the Bible in light of cultural values rather than interpret the culture in light of biblical values, we put a secular world view above God, as an idol. Theologian Willie Jennings says that too many Christians have “decided that we should look at the world as though we were at the center of it and not at the margins with a Jew named Jesus.” That’s idolatry.

It can be difficult to understand how people who seem genuine about their faith can set aside the two great commandments to follow racism rather than Christ. Professor Kate Bowler, who teaches American religious history at Duke University, uses the story of the Israelites worshiping the golden calf to explain why we people of faith are more susceptible to idolatry than we realize:

“In other words, we are much more likely to do exactly what the Israelites have done: not to have a false image of a false God, but a false image of the true God. We take great comfort in our own version of God instead. Perhaps one that is composed of bits of things I already know are good and golden, things I melted into a godlike form. Oh, is that an idol? It looked so familiar I hardly would have noticed.“

Fuller Seminary Professor Soong-Chan Rah (2009) agrees that the White church is “captive” to White culture. Rah generally writes to his fellow evangelicals, but his critique applies to those of us who are Mainline Protestants, Roman Catholic, and Eastern Orthodox, too.

“The current era of American Christianity marks the transition from a Western, white-dominated evangelicalism to an ethnically diverse evangelicalism. Despite this increasing diversity, US evangelicalism has demonstrated a stubborn inability to address the entrenched assumption of white supremacy. When whiteness is viewed as superior, the need to confront captivity to Western white culture is not recognized. This inability to engage cultural captivity allows the status quo of the white dominance of US evangelicalism.“

But what does that mean, exactly? Pastor and author Erna Kim Hackett offers this list of ways she has seen cultural captivity in the White Church. There are others, too, but this is a good place to start:

- Denial of systemic injustice

- Disregard for the lived experience of black people [and, I would add, other marginalized people—CWG]

- Silence in the pulpit

- A deeply ingrained superiority regarding issues of race

- A fixation on intentions over outcomes

Theologian Walter Brueggemann (2021) says that this gap between God’s high calling and the failures of God’s people is an old story. Brueggemann identifies these three principles of God’s kingdom as central to Old Testament teachings, from Exodus to Deuteronomy to Jeremiah and beyond:

- Hesed (steadfast love): to stand in solidarity with others.

- Mispat (justice): to distribute resources equitably so that everyone (including “widows, orphans, and immigrants”) has what they need.

- Sedaquah (righteousness): to intervene effectively in social affairs to address grievances, promote the general well-being, and rehabilitate society.

All too often, however, the people of Israel sought after the godless values of wealth and power, using worldly “wisdom” as the justification. Brueggemann notes that the pursuit of wealth and power—and justifying that with false narratives, including racism—also characterizes our society today. Rather than speak prophetically about love, justice, and righteousness, the church, because of its cultural captivity, often blesses the pagan, polytheistic desire for wealth and power, and often supports the pagan, polytheistic, and racist justifications for doing so.

Prophets for Our Time

Fortunately, the tools for dismantling the polytheistic idolatry of racist Christianity are part and parcel of true Christian faith. Contemporary prophets who have used those tools to identify and condemn racist Christianity often have been the marginalized, racialized people who are its primary victims. They are the ones who can teach the White church the “fierce love” described by the Rev. Dr. Jacqui Lewis (2021) of Middle Collegiate Church in New York City. The late Desmond Tutu is widely quoted as saying, “When the missionaries first came to Africa, they had the Bible and we had the land. They said, ‘Let us pray.’ We closed our eyes. When we opened them, we had the Bible and they had the land.”1

One such prophet is Professor Robert Chao Romero (2020), who teaches Chicana and Chicano Studies at UCLA. He says that for five hundred years, what he calls the Brown Church has offered a gospel alternative to the White nationalist church. The Brown Church emerged in this hemisphere shortly after the Spanish arrived, built by a few Spanish priests appalled by the genocide they were witnessing and indigenous Christians who could not believe that Jesus would endorse violent conquest. According to Professor Romero, the Brown Church espoused a Brown theology that was focused not only on the afterlife, but on this life as well. When they prayed, “Thy kingdom come, thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven,” they meant it. Romero uses the adjective Brown to represent both the skin color of many Latin Americans as well as the ethnic and cultural mix central to the Latino experience.

Romero likens the colonial Americas to Jesus’ home region of Galilee, pointing out that Galilee was a borderland with a mixed, in-between population despised by both the Roman empire and the Jewish elite. In several senses, Jesus was a Brown preacher from a Brown place with a Brown message that Romero calls El Plan Espiritual de Galilee:

“Jesus who heals the colonial wound. . . who meets us in the Christian-Activist borderlands, decolonizes our churches and institutions, and yet who also calls us into reconciliation with one another and our historic oppressors. Not a cheap grace and reconciliation that glosses over five hundred years of violence and racism that have killed, segregated, deported, and left hungry. No, a Spirit-led process of naming, resonating, repenting, decolonizing, and healing. . . Our goal is no less than the loving and liberating reign of the kingdom of God, the good news of Jesus of Galilee.“

Poet Kaitlyn B. Curtice (2020) writes about the racism she experienced in the White churches in which she grew up and the difficulty she had reconciling her love for Jesus with her Potawatomi identity. Many of the White Christians she knew believed that assimilating to White cultural norms was an essential part of being truly Christian. She left the church for a time, but she never left her faith. Curtice asks White Christians to separate their faith from their culture and see the beauty in all of God’s Kingdom, not just the White American portion of it:

“Once we open our imaginations to the value that Indigenous and Black people carry, it will inevitably create a different future for all of us, a future that God envisioned in the very beginning, a world full of fierce love and sacred belonging.”

Another prophet for today is Historian and Author Jemar Tisby (2020). In The Color of Compromise: The Truth about the American Church’s Complicity in Racism, Tisby writes:

“Jesus crossed every barrier between people, including the greatest barrier of all—the division between God and humankind. . . Therefore, we have the power, through God, to leave behind the compromised Christianity that makes its peace with racism and to live out Christ’s call to a courageous faith. The time for the American church’s complicity in racism has long past. It is time to cancel compromise. It is time to practice courageous Christianity.“

Like the nation, the church is at a critical juncture: Do we sacrifice our ideals in order to maintain White supremacy, or do we live out our ideals in genuine community with all God’s children? The answer to that question says a lot about our vision for God and the kingdom. Do we justify seeking wealth and power? Or do we pursue love, justice, and righteousness? Do we choose a small, manageable God who looks like us and thinks like us and affirms our basest prejudices? Or do we choose a large, out-of-control God who will mold us like clay into the work of God’s hand? Father Gregory Boyle (2017) asks us not to settle for less than God’s best:

“Human beings are settlers, but not in the pioneer sense. It is our human occupational hazard to settle for little. We settle for purity and piety when we are being invited to an exquisite holiness. We settle for the fear-driven when love longs to be our engine. We settle for a puny, vindictive God when we are being nudged always closer to this wildly inclusive, larger-than-any-life God. We allow our sense of God to atrophy. We settle for the illusion of separation when we are endlessly asked to enter into kinship with all.“

Frederick Buechner (1999) says that to have faith is to be homesick. I really like that. Scripture tells us we were created in the image of God. That does not mean we are almost as wise or almost as powerful or almost as holy as God. It means we have a capacity to comprehend God—dimly, yes, as through a glass, darkly—but with an ability to be moved, deeply, by glimpses of the divine. To stand in awe of the Holy and sense that the righteousness of God is the aim of our very lives, individually and together. Living in a fallen world as creatures of God makes us homesick for God’s kingdom, homesick for God’s shalom, homesick for justice, homesick to be part of the entire Body of Christ, not just one little piece of it. The idolatry of racism is a cheap substitute for true worship of the true God. Getting faith right can help us get race right—but getting race right can help us get faith right, too.

The Bottom Line: Everything about the Christian faith, including the teachings of Jesus, should make Christians the least racist people in the nation. But millions of White American Christians (though certainly not all) have given in to the temptation of White supremacy, selling their birthright for a bitter stew of ignorance and hate. Mercifully, God has raised up, for our benefit, prophets for our time. The question is: will we listen?

FOOTNOTES:

- This quotation likely was not original with Tutu; it has been in wide circulation for some time. See Gish, S.D. (2004).