The concept of race, as we have seen, is inextricable from racism itself. Both served to justify Europe’s colonization of the rest of the world. Because “race” is a concept with no biological or anthropological basis, we often talk about it as a “social construct.” Ibram X. Kendi (2019), however, says that it’s more accurate to call race a “power construct” because it is used primarily to maintain power for those who already have it.

Adolescence as an analogy for understanding the construction of race

Richard Delgado, a law professor at the University of Pittsburgh and author of several books on race in America, compares the concept of race to the concept of adolescence. In a posting on the blog blackprof.com, Delgado (2005) notes that there have always been people between 12 and 20, beyond childhood but not yet fully adult. However, it is only recently that we have thought of them as a special group, qualitatively different from those who are a little younger or a little older, and  essentially similar to each other in important ways. And while some aspects of contemporary adolescence are biological (puberty and acne come to mind), others are products of our time and place (such as the idea that teenagers should like their “own kind” of music or rebel against adult authority).

essentially similar to each other in important ways. And while some aspects of contemporary adolescence are biological (puberty and acne come to mind), others are products of our time and place (such as the idea that teenagers should like their “own kind” of music or rebel against adult authority).

Adolescence, then, is both a physical reality and a social construction. The fact that we classify people of a certain age as “teenagers,” and imbue that classification with certain expectations, leads them to internalize the label and leads us to see them as being more

alike than they really are.

Seeing Race

One more interesting bit of evidence: Law Professor Osagie Obasogie (2014) interviewed

over 100 people blind from birth about their conceptions of race. Turns out their thoughts about race are very similar to those of sighted people, in spite of the fact they cannot see the physical differences we think are so important. If anything, their experiences (e.g., being warned by others to learn the race of a prospective date before accepting any invitations to go out) indicate that race as a social construct is maintained with sufficient pressure and support that it needs no knowledge of any physical differences whatsoever.

Turns out White is a variable, not a constant

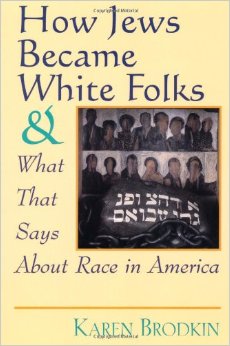

One of the few entertaining aspects of the racialization of humanity is to note how racial categories have changed over the years. Traveling across time has the same jarring effect as traveling across distance—some people are perceived to be one race during one era and another race during another era. The Census Bureau has measured race in many different ways over the decades, as our racial categories and definitions changed in response to political and social circumstances. Karen Brodkin (1998) has written a compelling book, How Jews Became White Folks & What that Says about Race in America.

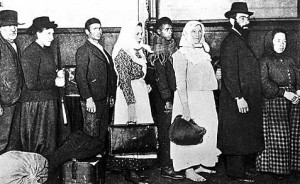

She begins with U.S. concerns about racial purity in the early 20th century. Immigration from Eastern and Southern Europe, the rise of intelligence testing (and the very low IQ scores most immigrants received, especially when they didn’t speak the language in which the test was administered), and the perversion of Darwinism into eugenics all came together at the same time. This created a great deal of anxiety among the Protestant elite about the future of a “mongrelized” America. Interestingly, many in the middle and upper classes at the time didn’t actually see themselves as “White,” but as “Nordic,” an important distinction because of their belief in not one but four European races. Volumes of “science” were written about the inherent racial differences among various European nationalities. There were the “Nordic” (including the English, but most certainly not the Irish), the “Alpine,” the “Mediterranean” and the “Semitic” races (listed here from best to worst, according to the received wisdom of the day). Because those group differences were perceived as racial, they were believed to be inherent and immutable, reflective of people’s essential character and capacity.

And the Jews? Because the “Semitic race” was considered inferior to all the rest, their immigration to America was the source of greatest concern.

Thirty years later, however, much was different. By the 1950s differences among Christians and Jews were believed to be religious or cultural, not racial, and largely ceased to be a source of concern for the future well-being of the country. World War II, and the accompanying Holocaust, did not erase anti-Semitism in America,1 but it did make many people more circumspect about talking openly about Jewish “treachery.” More important, says Brodkin, were the affirmative action programs for White people, mostly White men. New Deal Programs were designed to prop up working families, but the reality of racism meant that such programs got through congress only if people of color were excluded. The Federal Housing Administration offered subsidized mortgages, but only for White people buying in White neighborhoods. (Neighborhoods of color had red lines drawn around them on city maps—hence the term ‘redlining.’) Social Security dramatically reduced poverty for older Americans, but farm workers and domestic workers specifically were excluded, preventing most people of color from participating. The post-war GI Bill provided educational opportunities for millions of working-class men, including many who had limited opportunity before the war, but very few veterans of color were allowed to participate. Newly-White veterans went to college and entered the professions at unprecedented rates. Jews and Italians and Irish and Greeks and Bohemians—the grandchildren of the very people who were predicted to be the ruin of the nation— became, instead, evidence for the power of the American dream. And all Americans of European descent became White together. Brodkin writes,

As with most chicken-and-egg problems, it is hard to know which came first. Did Jews and other Euro-ethnics become white because they became middle-class? That is, did money whiten? Or did being incorporated into an expanded version of whiteness open up the economic doors to middle class status? Clearly, both tendencies were at work.

Federal programs designed to expand the middle class transformed the lives of millions of Americans from the 1930s to the 1950s–but only for those who were “White” (Katznelson, 2006). People of color worked just as hard, but with much less opportunity than White people had. And it made all the difference in the world.

Intentionally marginalizing other people, leaving them out of the American Dream, is the reason that the Rev. Dr. Jamie Washington, of Washington Consulting Group, doesn’t talk about minority groups. Being in the minority isn’t the point. He talks about “minoritized” groups, to emphasize the point that their status is sociopolitical, not natural, and intentional, not accidental.

FOOTNOTE:

- Antisemitism has ebbed and flowed for 2,000 years, but it has never disappeared. Sadly—and frighteningly—we are experiencing a significant increase in antisemitism today. Extremist propaganda is up, hate crimes are up, and violence against Jews is up as well. The Anti-Defamation League tracks antisemitism. Do a search for ‘antisemitism’ in the news section of your browser and read what’s happened recently. It’s bad.

The Bottom Line: The very concept of race is a political tool designed to maintain the power and resources of those in charge. One way to see that is to watch how the definitions of our racial categories have changed over time–and how those definitions are used to benefit some at the expense of others.