Which is worse: The fake news . . .

. . . or the real news?

Take note of the stereotypical comments and images you encounter in the next few days. They’re pretty pervasive. But why? Where do they come from? What gives them their power to shape our thoughts and feelings about other people? Melinda Jones (2002) identified four different origins of stereotypes.

The way we think creates stereotypes: Categorizing people into groups

We think in terms of the categories we create from our experiences. Those categories clarify the world for us, but they also over-simplify it. At some point, those natural over-simplifications cross the line into stereotypes. We can’t think without using our categories, which makes it difficult to know when our categories hinder, rather than help, our ability to make sense of things.

Simply knowing about social groups can lead us to stereotype their members because we assume there must be something important that led to their common classification in the first place, something that makes them essentially alike. We see close up the individual differences among members of our own social groups, but those in other social groups blur together in the distance into a homogeneous whole, everyone a minor variation on the same basic theme. Or, at best, an “exception”–a way of acknowledging that someone doesn’t fit your stereotype of their group without acknowledging that your stereotype might be wrong.

Aiden Gregg and his colleagues (2006) created fictional social groups for research participants, a stereotypical set of good guys and bad guys, and then set out to see how they could change people’s views of the groups. They tried adding new counter-stereotype information. They told people that over the years the members of the groups changed significantly. They even told one group that they got the names mixed up, and that everything people thought they knew about the groups was completely backward.

To no avail. The original views of the two groups persisted. As the authors concluded, category-based stereotypes are “like credit card debt and excess calories, they are easier to acquire than they are to cast aside.”

The things we hear create stereotypes: What we learn from other people and the broader society

We also pick up stereotypes from the world around us. We hear stereotypical talk or see stereotypical images. Family, friends, school, work, church, the media, etc. It’s easier to see stereotyping when its directed against you, of course. I’m a fan of British mysteries, and as soon as a character is introduced as a pious Christian, I know there’s a very good chance this person will be psychologically tormented and/or a complete hypocrite, and almost certainly will turn out to be the murderer. Odds are, however, I’m less likely to notice stereotypes of groups of which I’m not a part.

It can be difficult to know whether the information we read is accurate or whether it is influenced by stereotypes. For example, Grunwald, Nyarko, and Rappaport (2022) examined 14,000 Facebook posts from a wide array of U.S. law enforcement agencies. Sometimes they include information about arrests on their site and sometimes they mention the race or ethnicity of the person arrested. It turns out that the arrests of Black suspects were overrepresented on Facebook by 25%, on average, compared with their actual rates of arrest. This was especially true in communities that usually vote Republican and in communities with small Black populations. Citizens who follow their local law enforcement agency on Facebook probably are going to develop a distorted view of who commits crime in their communities (or have an already-distorted view reinforced) and they have no way of knowing that’s what’s happening.

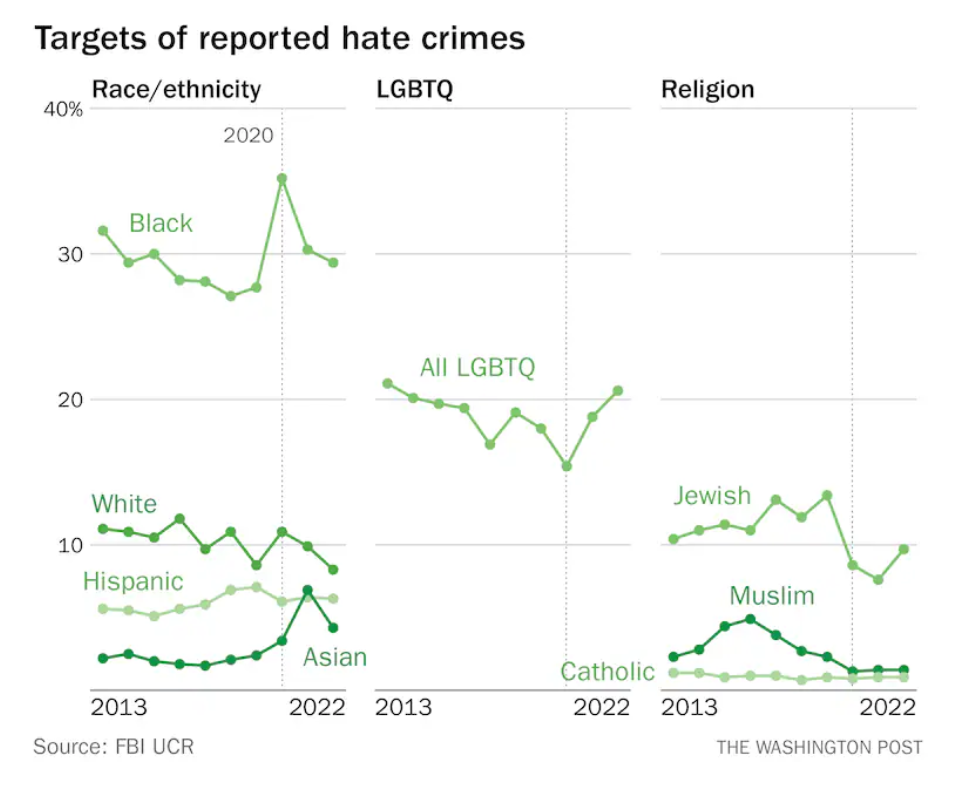

Similarly, Müller and Schwarz (2023) found that in 2016, as former president Donald Trump began tweeting negative things about Muslims, hate crimes against Muslims went up–especially in communities with a higher percentage of Twitter users. Using FBI hate crime statistics, Washington Post journalist Philip Bump (2023) noted that reported hate crimes over the last decade tended to mirror dominant news stories. Anti-Muslim hate crimes rose during the 2015 – 2016 presidential campaign, anti-Black hate crimes (already very high) rose during the publicity of the murder of George Floyd in 2020, and anti-LGBTQ hate crimes rose in 2020, 2021, and 2022 when quite a few Republican politicians began claiming that LGBTQ people were “grooming” children to be gay.

Of course, we can learn to stereotype from people whether they say anything or not. Three Italian psychologists(Castelli, Zogmaister, and Tomelleri, 2009) measured White children’s attitudes about both White and Black people. (Immigration from Africa to Italy has been a controversial issue in recent years.) Two-thirds of the children said they would prefer a White playmate to a Black playmate, and many of them described White people in more positive terms than they described Black people. The researchers also measured the attitudes of the children’s parents. The parents answered straightforward, explicit questions (e.g., “Black immigrants have jobs that Italians should have.”). They also took the Implicit Association Test (IAT), a measure of how quickly people associate positive and negative terms with Black and White faces. (The speed of our responses to pairs of words or concepts is a good measure of how strongly the two are connected in our minds.)

The best predictor of those White children’s level of explicit prejudice toward Black people? The mother’s implicit prejudice as measured by the IAT. The children picked up subtle cues from their mothers, and used them–not the mothers’ explicit statements–to form their own stereotypes.

Of course, the same kind of stereotype transmission happens here. If you think that younger generations aren’t absorbing racist messages, you haven’t been paying attention:

The ADL (formerly the AntiDefamation League, a civil rights organization that fights bigotry against Jews) did an extensive survey of U.S. attitudes toward Jews in 2022. Among other things, they found that exposure to anti-Semitism is greatest in the media, social media, and from politicians. Not many people reported hearing anti-Semitic remarks from friends and family in real life. However, when people did hear negative comments about Jews from people they knew, those comments had a big impact. People with anti-Semitic friends and family members were significantly more likely to hold anti-Semitic beliefs and attitudes themselves.

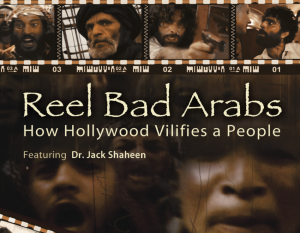

Sometimes the cues aren’t so subtle. The next time you hear someone describe anti-Arab sentiments as the result of 9/11, remind yourself of Jack Shaheen’s analysis of movie portrayals of Arabs throughout the 20th century: Reel Bad Arabs. Well before the 9/11 attacks, we were already culturally primed to see Arabs as basically alike, making it difficult to distinguish between the small minority that is violent and the large majority that is not.

The way we remember creates stereotypes: Illusory correlations

We are made such that we notice distinctive things—a single O in a field of Xs, a child in a group of adults, or a small number of women in a group comprised largely of men. What happens when two distinctive things occur simultaneously? We exaggerate the frequency with which it happens.

Here’s an example: Most people in this country are White, so people of color (in many contexts, at least) are distinctive. They get noticed. In addition, most people of any color usually do good things, not bad things, so bad behavior gets more of our attention, too. Put the two distinctive characteristics together, and we pay double attention to people of color doing bad things. The connection gets exaggerated in our minds and we “see” it as more common than it really is. The female manager with a prickly personality. The young Black guy who seems to glare at you in the parking lot. The older White man who is especially clueless about people who are different from him. The cognitive mechanism is complex (Ernst, Kuhlmann, and Vogel, 2019), but the bottom line is that a distinctive person doing a distinctive thing captures our attention and influences our subsequent thinking.

The inferences we make create stereotypes: Assuming the person equals the role

There is a tendency for those of us in Western cultures to over-estimate the extent to which people do what they want to do, and to under-estimate the extent to which people do things that are prescribed by their social roles. Therefore, when we see people in a particular role, we tend to assume that they are well-suited for it (and, by extension, not so well suited for other roles). For example, women are more likely to have responsibilities for rearing children, so on average they spend more time than men nurturing others. Seeing that, we come to believe that women are naturally nurturing, downplaying the extent to which they may simply be carrying out the responsibilities of their roles. Reverse the sex roles, and the impressions we have of the sexes change, too (Eagley and Steffen, 1984).

Race, like gender, determines many of the roles people hold in this country. People of color are over-represented in low-paying jobs, and therefore can seem to White people to be somehow destined for them. To the extent, then, that we are more likely to see members of particular groups in some roles, and less likely to see them in other roles, we develop stereotypes as a result.

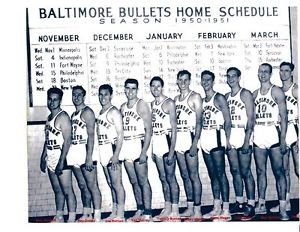

Stereotypes can shift as roles shift, sometimes in surprising ways. Psychologist and stereotype expert David Schneider (2004) points out that it was taken as a “fact” during his childhood in 1950s Indiana that Black people weren’t good athletes, a conclusion drawn from their near-absence on championship basketball teams. In hindsight, of course, it is easy to understand the sociological factors that prevented Black students from playing for the best teams, or kept the best Black teams from playing for championships. At the time, however, it seemed to Schneider and his friends like a logical deduction from their unbiased observations about the world of Hoosier sports. Now people watch NBA games and come away with the equally ludicrous conclusion that all Black people are innately hyper-athletic. What we believe depends, in part, on what we see—but what we see is a function of social roles and arrangements that are created by a complex set of historical, political, and economic factors.

The Bottom Line: Stereotypes are pervasive, and powerful, in part because they affect how we see the world even when our subjective experience leads us to believe we are simply describing the world as it actually exists. We rarely believe ourselves to be influenced by stereotype, making us even more susceptible to their effects.

THis content is look that very good.