I was talking with an advisee a few years ago about whether she wanted to major in English or biology. Suddenly, she interrupted me mid-sentence in a flat, almost distracted voice: “My mother always told me you can’t trust White people.” “Oh,” I said. “Do you want to talk about that?”

We’ve all been stereotyped at some time or another. For some of us, like me, it happens now and again, with little or no effect on our overall life circumstances. For others, it’s part of everyday life, and the impact is significant.

Three quick definitions:

- Stereotypes are cognitive—how we think about someone because of the group to which they belong.

- Prejudice is emotional—how we feel about someone because of the group to which they belong.

- Discrimination is behavior—how treat someone because of the group to which they belong.

Stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination sometimes work hand in hand. I don’t like you, I think you’re a bad person, and I treat you in hateful ways as a result.

BUT: It’s very important to know that many times they operate independently of each other. I may have absorbed stereotypes of people like you even if I don’t necessarily have prejudiced feelings toward you. Even if I do have negative beliefs and feelings, I may not discriminate because of legal or social pressures not to do so. Or I may discriminate even without any negative thoughts or feelings by participating in a larger group that excludes you in some way.

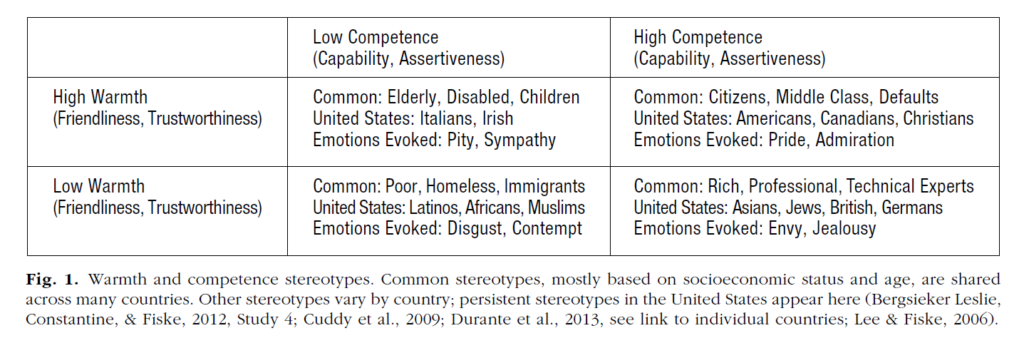

Cuddy, Fiske, and Glick (2007) have a helpful framework for understanding stereotypes and how they work. They call it BIAS: Behaviors from Intergroup Affect and Stereotypes. BIAS explains the ways our impressions of others are shaped by two primary factors: perceived warmth and perceived competence.

- Do we think a group of people is warm and trustworthy? That is, are their goals compatible with ours? Are we on the same side?

- Do we believe them to be competent and hard-working? The kind of people who can get something done when they put their mind to it?

Our answers will fall along a continuum, of course, but if we think in terms of yes/no responses to these two questions, we can see that stereotypes of other groups would fall into one of four broad categories (Fiske, 2018):

Paying attention to both dimensions can help us see stereotypical thinking that otherwise might go unnoticed. If I say, for example, that all Asians are smart (high competence), I may think that I’m not stereotyping because that’s a positive statement. BIAS helps me see that any kind of overgeneralization is a stereotype. Furthermore, it may well be accompanied by a negative belief, low warmth.

By the way, I used Asians as an example here because dominant views of Asians are an excellent example of the complexities of stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination. You can read more about that here, here, and here.

The Black History Month Story tells us that there are some nasty bigots out there wearing sheets, and they’re the ones who stereotype, the ones who are prejudiced, the ones who discriminate. But the history we all inherited is the history we all inhaled. Denying our stereotypes, or simply failing to recognize them, gives them power over the ways we think and feel and act. Confronting our stereotypes, and learning to overcome them, gives us the power to keep them in check and to treat others as we would like to be treated ourselves.

The Bottom Line: The history we inherited is also the history we have inhaled. We have absorbed it in ways we usually don’t even recognize, giving it power to shape our thoughts, feelings and behaviors, whether we want it to or not.