The Two Dimensions of Race

A middle-aged couple in San Diego has decided to take a vacation, heading across the continent by car, all the way to Maine.

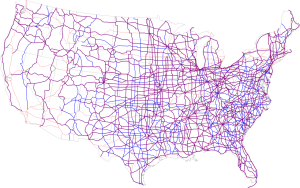

They bought a road map, and each of them has been studying it, albeit in some pretty odd ways. He holds the map flat out in front of him, at eye level, as if he were standing in the Pacific Ocean, facing east, with the country laid out before him. From this vantage point, he can see clearly that they are starting at the southern border of the nation and need to travel north. She, too, keeps the map flat at eye level, but turns it ninety degrees from the way her husband holds it. As if standing in the Gulf of Mexico, she places her nose at New Orleans and eagerly follows their itinerary from west to east.

Their departure date arrives, they pack the car, and he remarks that he’s excited to be traveling north across the country. Stunned, she replies, “Don’t you mean east?” An argument ensues, and they spend their vacation sitting in the driveway quarreling about how to get to Maine. “We’re a stone’s throw from Tijuana,” he explains, “and we’re going to end up fifty miles from New Brunswick. Everyone knows that you have to travel north if you want to get from Mexico to Canada.” “Don’t you know anything about geography?” she retorts. “We start at the Pacific and we end at the Atlantic. How on earth—literally!—do you expect to make it if we don’t go east?”

The “horizontal dimension” of social culture

When different social groups live together in the same society, there are nearly always two dimensions to their interrelationships: the “horizontal” dimension of culture and the “vertical” dimension of social power. The cultural dimension is horizontal because it is, on average, value-neutral. Cultures vary in their answers to fundamental questions about life (Ting-Toomey, 1999; Geert Hofstede’s six dimensions of national culture). These questions include, among others, “What is the relationship of the individual to the group?” “What is the most important aspect of time—past, present, or future?” “How should we treat differences in gender, age, and rank?” There is an infinite number of potential answers to these kinds of questions, leading to the amazing variety of cultures in the world. There are 9.2 quintillion possible ways to complete the NCAA March Madness bracket, so it seems unlikely that we soon will exhaust the possibilities people can devise for living together in a shared culture.

When different social groups live together in the same society, there are nearly always two dimensions to their interrelationships: the “horizontal” dimension of culture and the “vertical” dimension of social power. The cultural dimension is horizontal because it is, on average, value-neutral. Cultures vary in their answers to fundamental questions about life (Ting-Toomey, 1999; Geert Hofstede’s six dimensions of national culture). These questions include, among others, “What is the relationship of the individual to the group?” “What is the most important aspect of time—past, present, or future?” “How should we treat differences in gender, age, and rank?” There is an infinite number of potential answers to these kinds of questions, leading to the amazing variety of cultures in the world. There are 9.2 quintillion possible ways to complete the NCAA March Madness bracket, so it seems unlikely that we soon will exhaust the possibilities people can devise for living together in a shared culture.

I am not a cultural relativist, so I do not believe it impossible to judge others’ cultural practices. Still, things can look very different from inside a culture than they look from the outside. Every culture has something positive to offer the rest of the world, and something that it profitably could learn from others. Differences in culture, then, generally average out to be value-neutral, which is why I think of this as a horizontal—east-west—dimension.

The “vertical dimension” of social power

In addition to culture, social groups also differ in their access to important and necessary resources—wealth, education, power, and prestige, to name a few. Let’s call this dimension “social power” because power—by definition the ability to make decisions that affect other people—is the means by which all other resources get allocated. This is a vertical—north-south—dimension because it is a hierarchy, and being at the top is way better than being at the bottom. Not morally superior, mind you–often, quite the opposite. But it does provide the resources necessary to care for oneself and one’s family in the present and for the future.

Average group differences in social power do not mean that everyone within a group possesses the same amount of power. Nonetheless, those average differences are very important in determining the opportunities available to individual group members, even if they do not exercise that power personally. As we saw time and again in the section on The History We Inhaled, how other people perceive the social groups to which we belong go a long way in determining how they see us.

Race Forward has some very good, short videos on systemic racism that help explain the vertical dimension and how it works.

As we will see in the next section, we tend to “inhale” the world in which we live, meaning that our ways of thinking and behaving often reflect our social experiences. According to DeSante and Smith (2020), White people’s attitudes about race mimic the two dimensions of race. The first (the horizontal dimension) is our emotional response to people of color. Are we afraid of them, as the stereotyped messages we’ve heard tell us we should be? Or are we empathic with them, recognizing that, on average, they have a much more difficult time living in this country than White people do? The second (the vertical dimension) is our beliefs about racism and racial disparities in the society: do we recognize what’s going on, and its effects, or do we deny that such disparities exist? DeSante and Smith have found that where White people stand on these two dimensions predicts quite a bit about them, including their political orientation and their views on “racialized” issues such as the government safety net. We live in the two dimensions of race and we carry them around inside us.

This happens remarkably early. Rizzo, Britton, and Rhodes (2022) found the White children as young as four notice racial disparities; what they believe about those disparities shapes their views on race. Those who believe that disparities result from intrinsic differences between White people and people of color are more prejudiced; those who believe that structural factors at work are less prejudiced. Such is the power of race and racism in the U.S., that it has such an influence at such a young age.

Reading a two-dimensional race map

Trying to understand relationships among social groups by looking only at the cultural dimension, or only at the power dimension, is like trying to read a road map by looking only at north-south or only at east-west. It is a one-dimensional view of a two-dimensional diagram. However, while most of us have learned how to read a two-dimensional road map, few of us know how to read a two-dimensional race map. Instead, we walk around with our race maps flat at eye level, focusing on just one dimension and arguing with those who have their maps turned differently from ours.

Which brings us back to our couple from San Diego, still stuck in the driveway and still angry. They both want to take this trip. Indeed, they want to go to the same place. They each know something important about how to get there.

However, they are so focused on one dimension of their map that they cannot see the other. North-south and east-west are complementary, not competitive. If you’re sitting in a San Diego driveway dreaming of lobster in Bar Harbor, you better consider them both. But if you spend all your time promoting north at the expense of east, or east at the expense of north, you might as well order take-out and grab a good book, because you’re not going anyplace for a while.

The Bottom Line: There are two dimensions to race, just as there are two dimensions to a map, and if you don’t pay attention to both of them, you’re going nowhere fast.