to racial progress

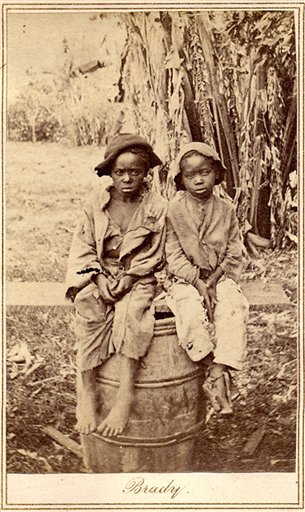

According to Historian Hasan Kwame Jeffries, James Madison, the fourth president of the United States, is known as the Father of the Constitution. The version he wrote, however, was opposed by many who believed it did not do enough to ensure individual rights. Rather than re-write the constitution itself, Madison offered to add ten amendments. He retreated to his Virginia home, Montpelier, settled into his library on the second floor, and wrote what we now call the Bill of Rights. If you walk down two flights of stairs from Madison’s library into the cellar, you can see the hand-made bricks of Montpelier’s foundation. Look closely, and you can see the handprints of the brick makers. Little handprints. Children’s handprints. The Bill of Rights—which guarantees us freedom of religion, speech, and assembly; the right to due process; the right to a jury trial; the right to avoid self-incrimination; and freedom from cruel and unusual punishment—our beloved Bill of Rights was written in a mansion with a foundation of bricks made by enslaved children.

It stuns me to know that, by some accounts, the first African slaves were brought to the Western Hemisphere in 1501, less than a decade after Columbus and his crew arrived at Hispaniola. Over the next 300 years, as the institution of slavery was expanded and embedded into U.S. life, it became what Biologist Joseph L. Graves (2004) quite rightly called a “sustained act of genocide.” Let’s begin with this excerpt from The Shaping of Black America by Lerone Bennett, Jr. (1975), historian and editor of Ebony magazine from 1954 – 2006. It’s long, but please read it slowly and let it wash over you.

“No one knows the hour or the day of the black landing. But there is not the slightest doubt about the month. John Rolfe, who betrayed Pocahontas and experimented with tobacco leaves, was there; and he said, in a letter to his superior, that the ship arrived “about the latter end of August” in 1619. Rolfe had a nose for nicotine, but he was obviously deficient in historical matters, for he added gratuitously that the ship “brought not anything but 20 and odd Negroes.” Concerning which the most charitable thing to say is that John Rolfe was probably pulling his superior’s leg. For in the context of the meaning of America, it can be said without exaggeration that no ship ever called at an American port with a more important cargo. In the hold of that ship, in a manner of speaking, was the whole gorgeous panorama of black America, was jazz and the spirituals and the Funky Broadway. Bird was there and Bigger and Malcolm and millions of other X’s and crosses, along with Mahalia singing, Gwendolyn Brooks rhyming, Duke Ellington composing, James Brown grunting, Paul Robeson emoting, and Sidney Poitier walking. It was all there in embryo in the 160-ton ship.

The ship that sailed up the James on a day we will never know was the beginning of America, and, if we are not careful, the end. That ship brought the black gold that made capitalism possible in America; it brought slave-built Monticello and slave-built Mount Vernon and the Cotton Kingdom and the graves on the slopes of Gettysburg. It was all there, illegible and inevitable, on that August day. That ship brought the blues to America, it brought soul, and a man with eyes would have seen it, would have said that the seeds of an Alcindor are here, would have announced that a King was coming and that a Du Bois would live and die, would have foretold agonies and pains and funerals, would have predicted four hundred years of Sundays and Saturday nights. A man with eyes, 1 say, would have seen all that in the twenty black seeds planted that day and in the bad faith of whiteness that would manure them. He would have seen it all, and he would have stood up and announced to his startled contemporaries that this ship heralds the beginning of the first Civil War and the second.

From “Decades of Hope” to “a Chain of Betrayal”

In the years right after 1619, many laborers came to the Western Hemisphere under duress or entirely against their will. Early on, both Europeans and Africans were indentured servants rather than slaves, men (and a few women) who would be forced to work for little or no pay for a specified number of years and then freed from bondage. Lerone Bennett, Jr. explains that race didn’t have anywhere near the meaning then that it does today. People we would call Black and people we would call White worked side by side in indentured servitude and in freedom. Some Black people owned property, and they could participate as full citizens in social and political life. A few held public office. Europeans and Africans married and reared children together. The vestiges of that time linger in our genes even today. Bryc et al. (2015) looked at 23andMe genetic analyses of 150,000 White Americans and found that a significant minority of them had African and/or Native American ancestors—most of whom entered their lineage during the 1600s. Bennett even calls the first half of the 17th century “decades of hope and some promise” for Africans in North America.

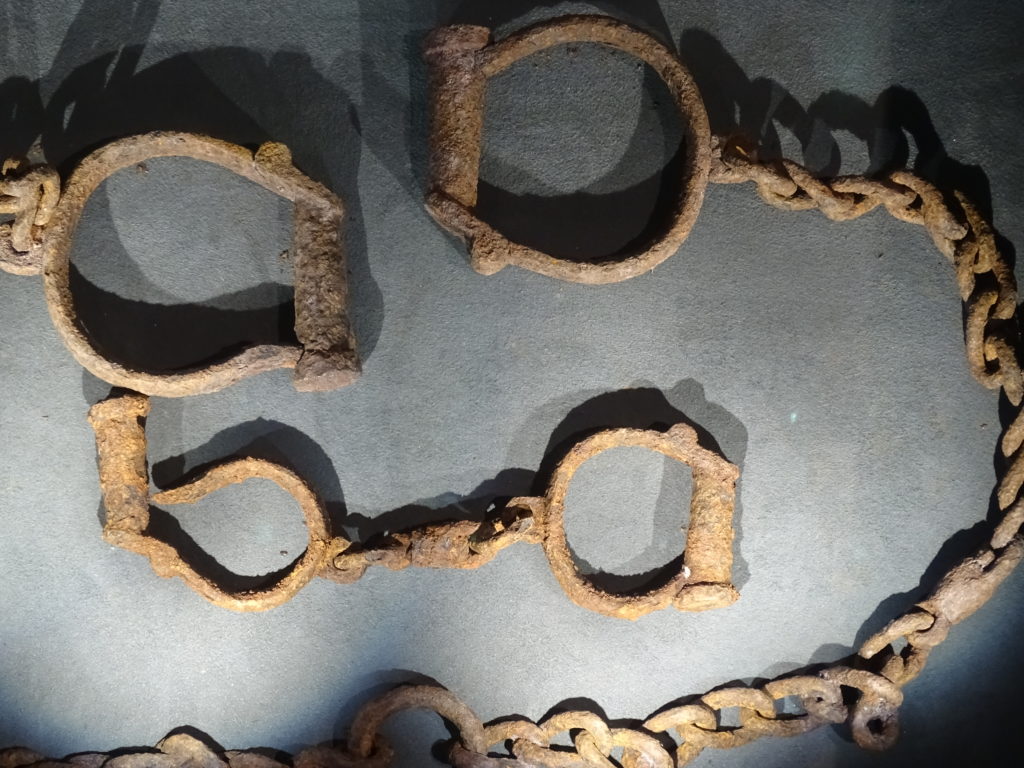

By the middle of the 1600s, however, things began to change. Fewer indentured servants were brought from Europe even as the demand for labor was increasing; as a result, more Africans were brought and fewer were given the opportunity to work their way out of bondage.1 If they sued for their freedom, courts were increasingly likely to rule that they did not have to be released at the end of their contract.2 More and more indentured servants were kept on for a lifetime, and more Africans were brought to North America with an expectation that they would spend the rest of their lives working for others for no pay—and that their children would do the same. (This is one reason U.S. slavery is known as chattel slavery. Slavery was part of many cultures across the centuries, but American slavery was exceptionally brutal.) A fundamental American value was born: the financial well-being of White Americans takes precedence over the human rights of Black Americans. Over time, White and Black became social categories, not just descriptions of individual people. White elites, always worried about working people joining forces against them, found it useful for poor and powerless Europeans to identify with the elites as White, rather than with poor and powerless Africans, who became Black. (Sounds familiar, doesn’t it?) Labor activist and historian Theodore W. Allen (1997) refers to this divide-and-conquer strategy as “the invention of the white race.”3

“Race is Strategic. Race does ideological and political work.”

—Michael Omi and Howard Winant, Racial Formation in the United States

These trends continued throughout the 1700s. Unfortunately, things got worse for enslaved people when the U.S. became an independent nation. As we already have seen, Lerone Bennett, Jr. was a master wordsmith. This is how he described race in the early years of the United States:

“For most white Americans the American Revolution was the first link in a chain of hope. For most black Americans the American Revolution was the last link in a chain of betrayal.”

Why? For one thing, while the Declaration of Independence was a clarion call for liberty and equality (except for Native Americans, who were described as “savages”), the constitution is a much more conservative document. Historian David Waldstreicher (2009) even called it “slavery’s constitution.” He writes, “Because proslavery forces were able to make deals to protect their interests in particular, slavery itself gained the protection of the federal union while being protected from that union’s new powers.”

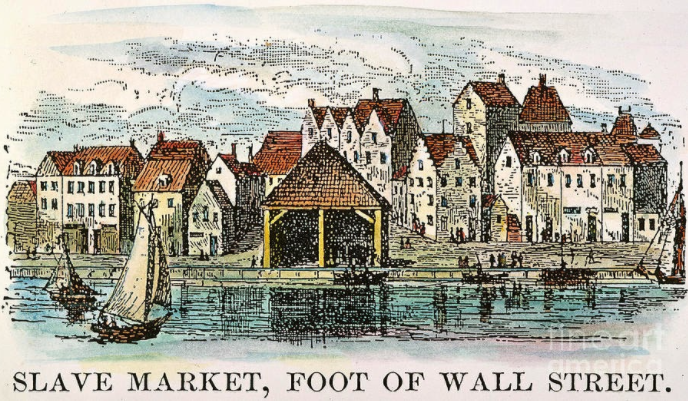

When you read “proslavery forces,” please don’t translate that as “Southern.” Slavery existed throughout the colonies during this time, North and South. You may not be surprised to know that in the 18th century, Charleston, South Carolina, had more enslaved people than any other city in North America. The city with the second-largest number? New York.4 Forty-one percent of New York households owned enslaved people, and that figure is even higher than it was in Charleston. The last enslaved New Yorkers weren’t emancipated until 1827. Many Northern slave-owners benefitted mostly from the work of their own slaves, people like farmers and small business owners in New Jersey and upstate New York. But the real money went to Northerners who profited from large-scale slavery in the South, especially cotton and tobacco. A lot of raw cotton was shipped north, especially to Massachusetts, where textile mills transformed it into fabric. New York City ports shipped fabric and tobacco to Europe. Rhode Island shipyards built the ships for sailing fabric and tobacco overseas—and for bringing enslaved Africans back to the U.S.5 Connecticut insurance companies sold policies to everyone involved. Much of the wealth generated from Southern slavery ended up north of the Mason-Dixon line, and many well-to-do Northerners were invested both financially and emotionally in maintaining slavery even if they didn’t own any slaves themselves.6

A Slave Society

This system expanded dramatically with the invention of the cotton gin in 1793. At that point, says Historian Ira Berlin (1998), the U.S. made an important shift, from being a society with slaves to being a slave society. In a society with slaves, enslaved labor is “just one form of labor among many.” It is a brutal form of labor, but it does not dominate the economy as a whole. On the other hand, writes Berlin,

“In slave societies, by contrast, slavery stood at the center of economic production, and the master-slave relationship provided the model for all social relations: husband and wife, parent and child, employer and employee, teacher and student. From the most intimate connections between men and women to the most public ones between ruler and ruled all relationships mimicked those of slavery. . . Whereas slaveholders were just one portion of a propertied elite in societies with slaves, they were the ruling class in slave societies . . .“

I find Berlin’s analysis helpful. It explains that one reason the U.S. still can’t come to grips with slavery and its consequences is that it molded our society so deeply we simply can’t envision another way of being.7

Not all Black Americans were enslaved, but even free Black Americans were subject to severe forms of discrimination. The late Stanford University Historian George M. Fredrickson wrote, “ ‘Free Negroes’ in the Northern states were often segregated and denied legal and political rights; some states and territories even prohibited their entry.” He also noted that while some free Black Americans had the right to vote in the early years of the republic, when suffrage was extended to all White men in the 1820s and ‘30s, it was taken away from most Black men.

Most churches adapted themselves to the norms of a slave society, Quakers being the notable (but inconsistent) exception.8 Lerone Bennett, Jr. offers the Baptists and Methodists as good examples. At the time of the revolution, both denominations took strong anti-slavery stances. In fact, after independence, the Methodists gave their itinerant preachers only twelve months to free any people they owned. But such initiatives soon gave way to the reality that slavery was becoming more entrenched under independence, not less. Churches that previously held integrated worship services, for example, built balconies and separate entrances for Black parishioners to use.

In response, many Black people formed their own congregations and denominations. The African Methodist Episcopal (AME) church was created during this time, for example. Jesus’ invitation to “whosoever will” was no match for the power of White supremacy, even for those who were convinced they were the better Christians.

In the first half of the 19th century, violence against Black people increased, segregation became more entrenched, and Black people (even free Black people) and White people started living in two completely different social worlds. In addition to separate churches, Black people had to form their own businesses, mutual aid societies, fraternal organizations, schools, cultural institutions, and newspapers. This kind of hyper-segregation seems so natural to us today we hardly notice it. But it isn’t natural; it was manufactured, intentionally, at the birth of the nation, and it has shaped life in the U.S. ever since.

As it turned out, the center could not hold. War ensued. And we’re still arguing about that.

The Fight over the War over Slavery

In 1970, I was in the eighth grade in Nashville, Tennessee. I took a team-taught U.S. history course. When the time came to study the Civil War, one of my teachers (a White man) made it very clear that slavery was a side issue. The real cause of the war, he told us, was that the North wanted high tariffs on imported manufactured goods because they did a lot of manufacturing. The South wanted low tariffs so that imported goods would compete with Northern products and make them less expensive. My other teacher (a White woman) was having none of that. She insisted that slavery was at the heart of the war, and told us, too, that the fight was continuing. When she invited a civil rights attorney to speak to us, it was the first time I’d ever seen a professional Black woman9—a completely new idea for me. School desegregation was a hot topic in Nashville at the time. The attorney and my teacher were the first two people I knew (other than the NAACP lawyer on the news every night) who thought that integration was a good idea. I didn’t understand the details of their argument, but the idea that contemporary fights over desegregation were rooted in the Civil War lingered in my mind.10

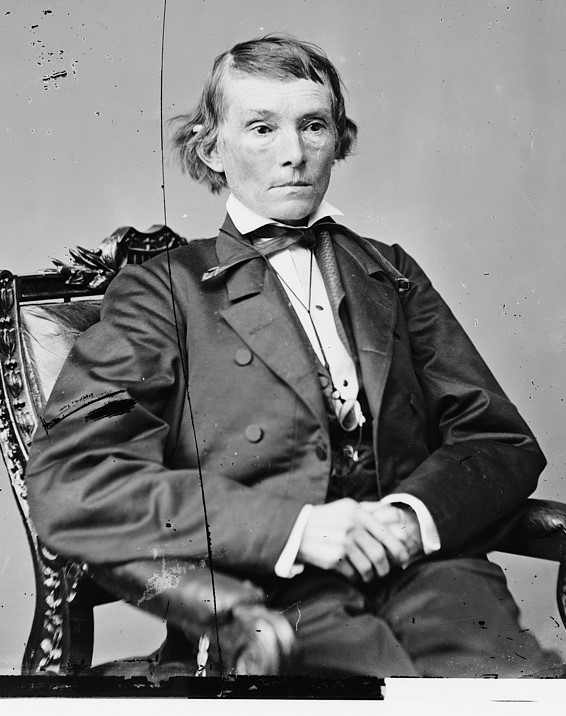

You don’t have to take Mrs. Freeman’s word for it. If you want to know whether slavery was central to the Civil War, just listen to the Vice President of the Confederate States of America, Alexander Stephens, as he explained shortly before the war why he believed the CSA would be superior to the USA. This has come to be known as “the cornerstone speech.”

“These ideas [of liberty and equality in the American Revolution], however, were fundamentally wrong. They rested upon the assumption of the equality of races. This was an error. It was a sandy foundation, and the government built upon it fell when the ‘storm came and the wind blew.‘

Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its corner-stone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth.“

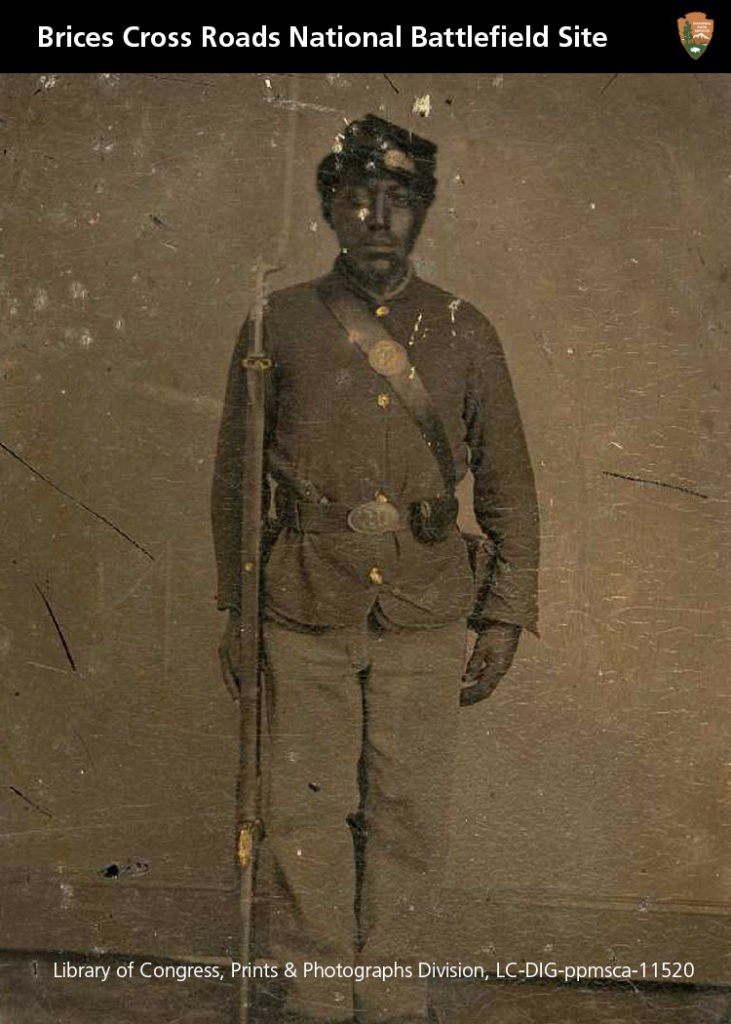

The Civil War was long and bloody. Hundreds of thousands died; many more were wounded. Approximately 200,000 Black soldiers fought with the Union, making up about 10% of the Union Army. 40,000 of them died. They fought in segregated units, under White command, and didn’t always get paid as much as White soldiers. They often experienced discrimination in the North and were in grave danger when they were captured as POWs by the South. In at least one case, when Black Union soldiers surrendered, expecting to be taken prisoner, they were massacred instead.

The Real Jim Crow

In an article she wrote for the National Archives, Miranda Booker Perry explains that after the war ended, there was almost nothing done to help newly-freed people get on their feet. Most had nowhere to live and nowhere to work. The South was completely impoverished by the war. Jobs were scarce even for White people, and Black people had a much more difficult time finding work. General Sherman issued orders for freed Black people in the South Carolina low country to be given plots of farmland so they could feed themselves. They received a three-year lease with the possibility of purchasing the land outright. The Freedmen’s Bureau had similar plans for the rest of the South. (This is the plan we know today as “forty acres and a mule.”) Just a few months later, however, President Andrew Johnson rescinded Sherman’s order, evicted the Black people from the land, and made it available to White people for “homesteading.” Dr. Perry quotes Carter G. Woodson, a pioneer in the field of African American History, who described post-war Black Americans as “nominally free but economically enslaved.” Hunger was rampant, as were disease and death. Historian Jim Downs (2012) put it like this: “Without access to food, clothing, medical care, and even a place to bury their loved ones, the promise of freedom could not be realized for many people.”11

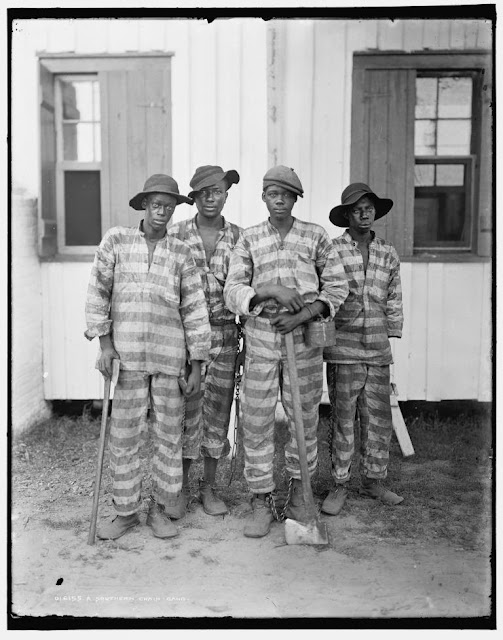

The whole next century was bleak. Grim. In his Pulitzer-prize winning book, Slavery by Another Name, Journalist Douglas A. Blackmon (2008) recounts the re-introduction of slavery in the South after Reconstruction. Southern states (where nearly all Black Americans lived at the time) developed a convict-leasing system to provide cheap labor to factories, farms, and mines. Upward of 200,000 Black men (approximately 10% of all the Black men in the entire nation) were arrested on trumped-up charges, such as not having a job or talking with a White woman. After a sham trial, they would be presented with a bill for all the costs associated with their arrest, incarceration, and conviction. Very few Black people could afford to pay the bill, so they were sent out to work for local employers. The entirety of their salary went to settle their bill at the jail; sometimes the longer they worked the more they owed. It was common for local employers to let the police and the courts know how many laborers they needed in the coming weeks and the number of arrests would rise or fall accordingly. Conditions were brutal; men died of severe physical punishment as well as the diseases that fester in filthy living conditions. Their families suffered, too, of course, financially and psychologically. It was part of a broader political system of terrorism, designed to keep Black Americans living in fear for generations after the Civil War ended. As Blackmon described it,

“[T]his slavery did not last a lifetime and did not automatically extend from one generation to the next. But it was nonetheless slavery—a system in which armies of free men, guilty of no crimes and entitled by law to freedom, were compelled to labor without compensation, were repeatedly bought and sold, were forced to do the bidding of white masters through the regular application of extraordinary physical coercion.”

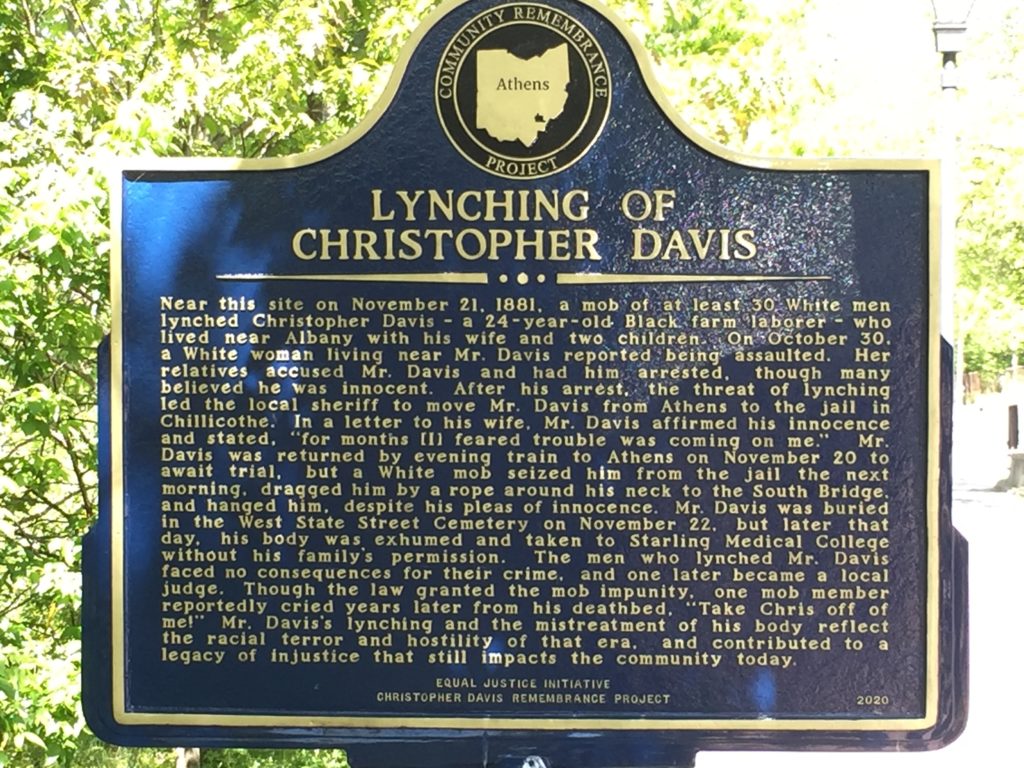

Convict leasing was just one manifestation of mass incarceration, and mass incarceration was just one manifestation of the “Jim Crow” policies that ran from the end of Reconstruction in 1877 to the civil rights legislation of the 1960s. It is no exaggeration to describe this era as a reign of terror. The subjugation of Black Americans was maintained with both the threat of violence and violence itself. Lynching (the brutal murder of Black people in order to terrorize the Black population as a whole) was common. According to a report by the Equal Justice Initiative,

“Between the Civil War and World War II, thousands of African Americans were lynched in the United States. Lynchings were violent and public acts of torture that traumatized black people throughout the country and were largely tolerated by state and federal officials. These lynchings were terrorism. “Terror lynchings” peaked between 1880 and 1940 and claimed the lives of African American men, women, and children who were forced to endure the fear, humiliation, and barbarity of this widespread phenomenon unaided.”

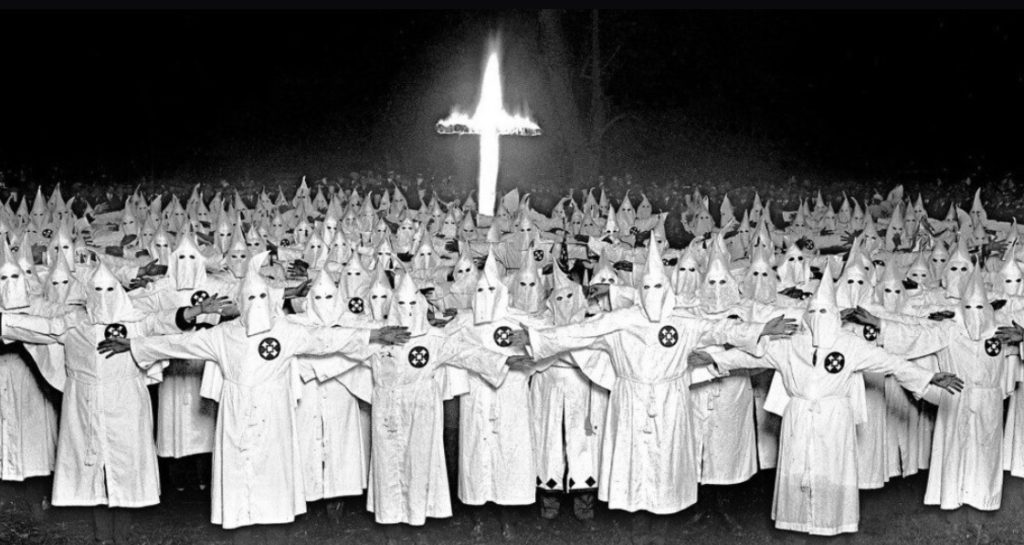

The Klan, founded in 1865, came back strong in the early 20th century. The “Lost Cause” movement romanticized and ennobled the Confederacy. It was during this time that public statues of Confederate leaders were built and that streets, parks, schools, and military installations were named in their honor.

Historian Paul Ortiz (2018) puts it in a broader context: “Inequality was enforced with the whip, the gun, and the United States Constitution. Jim Crow and Juan Crow laws, backed by law enforcement and paramilitary organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan, stood like flaming sentinels against Black and Brown progress.”

Thanks to The Black History Month Story, when most White people think of Jim Crow, they think of segregation in public facilities—buses, bathrooms, and water fountains. But things were much worse even than that. Jim Crow was a pervasive set of policies and practices designed to re-enslave Black people, to keep them at the very bottom of the social ladder, with very few rights and very few opportunities.

Jim Crow in the North—and around the Country

Escaping Jim Crow was the reason for The Great Migration in which over six million Black Americans moved out of the South between 1910 and 1970 (when the out-migration trend reversed). Some things were better in the North and the West—there were more jobs, for example—but Northern and Western states and cities soon developed a Jim Crow system of their own. Redlining, in conjunction with White flight, created and maintained highly segregated neighborhoods that still exist today (Winling and Michney, 2021). The impact of redlining was so severe that Richard Rothstein (2018) says that the traditional distinction between de jure segregation (mandated by law) and de facto segregation (naturally occurring) is a myth because our individual choices have been so thoroughly shaped and constrained by racist law and policy. Redlining still happens: here is just one example.

Residential segregation meant that schools were highly segregated, too. Businesses left Black neighborhoods. Many banks wouldn’t make loans to Black people to buy a home or start a business. In fact, they wouldn’t support any kind of investment in Black areas at all, including loans for home maintenance or improvements. Over time, jobs disappeared, the housing stock deteriorated, and many Black families in the North found themselves once again in areas of concentrated high poverty. The effects have persisted over the generations; we see them in the Black-White gap in economic upward mobility in the North even today (Derenoncourt, 2022).

In The Strange Careers of the Jim Crow North, Historian Brian Purnell and Political Scientist Jeanne Theoharis (2019) point out that segregation and political disenfranchisement began in the North long before the Civil War, so it wasn’t surprising that such practices continued after the war–and into the present day. They quote Rosa Parks as describing Michigan, where she moved after she left Alabama, as “the Northern Promised Land that wasn’t.” They also quote Malcolm X, who likened Southern Jim Crow to a predatory wolf and Northern Jim Crow to a sly, conniving fox.12 Their description of Jim Crow in the North is an excellent picture of how contemporary racism works, often behind the scenes, throughout the country:

“A close examination of the history of the Jim Crow North demonstrates how racial discrimination and segregation operated as a system, upheld by criminal and civil courts, police departments, public policies, and government bureaucracies. Judges, police officers, school board officials, PTAs, taxpayer groups, zoning board bureaucrats, urban realtors and housing developers, mortgage underwriters, and urban renewal policy makers created and maintained the Jim Crow North. There did not need to be a “no coloreds” sign [in order] for hotels, restaurants, pools, parks, housing complexes, schools, and jobs to be segregated across the North as well.“

As has always been the case, thought leaders in society got busy justifying the nation’s racism. Psychologists, anthropologists, medical professionals and others sought “scientific” justifications for racist beliefs and practices. Church leaders stepped up to bless racist ideas. So did presidents and other politicians. I know I say this a lot, but the same thing happens today. When my county commissioners abolished the county’s Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Office and then changed the county motto from “Where you belong” to “Where freedom rings,” you know exactly what freedom they’re talking about: the freedom of White people to exploit and exclude people of color.

A Case Study: How 21st Century Racism Took Shape in the Early 20th Century

Historian Eric Yellin (2013) offers a fascinating example of how things got worse for Black Americans in the early 20th century. Woodrow Wilson was elected president in 1912 as a progressive. But he was also deeply racist, and—as we often do—he convinced himself that there was no tension between his two contradictory sets of beliefs. When he came into office in 1913, Washington, D.C. was one of the few U.S. cities with a sizeable Black middle class. That’s because most Black voters (in the places where Black people were allowed to vote, of course), were part of the Republican party, and GOP presidents had appointed a number of Black people to federal jobs. Not the cabinet or anything like that, but as clerks—sometimes higher-ranking clerks—in places like the Census Bureau and the Treasury Department. We’d think of them today as low-to-mid-level bureaucrats. Even though DC was largely segregated, federal buildings were not. Not the offices, the cafeterias, or even the bathrooms. Wilson and several of his appointees set about changing that. A small number of bathrooms (often just two, even in a large building) were set aside for Black people. Cafeterias were re-designed for separate eating areas, as were the workspaces themselves. Many Black workers were demoted, with significant cuts in their salaries. Especially for those with the best jobs, the pay cuts were devastating. Their lives were never the same again. There was literally no other job they could get that would pay them anywhere near as much.

All this was cloaked in the language of progressive reform. The Wilson administration consistently said that the new policies were simply a way to “reduce friction” and “maintain harmony” in the workplace. From that perspective, segregation was not racist; it was the cure for racism. As I read Prof. Yellin’s account of Wilson’s attack on Black federal workers, I was struck again and again how contemporary it all sounds. It brings back so many memories of committee meetings, public forums, organizational pronouncements, and all the ways White people and institutions maintain racial boundaries while pretending to themselves and others that their motives are not racist. Some examples from Prof. Yellin’s book:

- Wilson’s administration decided not to put up signs indicating that facilities had been segregated. Instead, they talked with Black employees and advised them to follow the new rules on their own—for their own sake and protection.

- Black employees who had demonstrated the most ambition to get ahead were most likely to be demoted or dismissed.

- A few people were “promoted to racial isolation.” For example, some Black employees in the Census Bureau were put in charge of a new office that focused solely on data pertaining to Black people. The bureau wasn’t interested in the work, making the job a professional dead end.

- White racists who made accusations against Black colleagues generally were taken at face value, often resulting in sanctions against Black employees.

- Wilson’s policies reduced the number of Black employees and concentrated those who were left in the most menial jobs, but the administration claimed that was the fault of the employees themselves. “If African Americans were disproportionately in lower ranks of government service, Wilsonians insisted, this said more about people of African descent than about their employer.” This is how, Yellin explains, that “[f]alse meritocracies can transform socially constructed hierarchies into natural expectations.”

- When Wilson agreed to meet with an African American leader, William Monroe Trotter, to discuss Wilson’s attack on Black employees, he adopted a paternalistic and patronizing tone that highlighted the very prejudice he denied. “The American people, as a whole,” Wilson said, as if Black Americans weren’t American, “sincerely desire and wish to support, in every way they can, the advancement of the Negro race in America.” He went on to say that it would be “unwise” to ignore the racism of White federal employees because “friction” might result. Best, then, to be “practical,” to “strip this thing of sentiment and look at the facts.” Wilson himself was not the problem, he insisted. Those questioning his policies were the ones creating problems that otherwise wouldn’t exist. He even went so far as to portray himself as the victim in the story, a well-intentioned White person having to deal with angry Black people who refused to be reasonable.

As Yellin explained, Wilson’s approach was to “deny and defend” racism with “claims of neutrality and meritocracy.” I wish I’d read Yellin’s book forty years ago. It took me a lot longer than it should have to understand that denial and defense are two sides of the same coin, that powerful White people often try to make racism look like the neutral, meritorious stance. I just wish I knew how much self-insight people have when they defend racism in this way. Do they understand what they’re doing? Or are they simply following a script from which apologists of White supremacy have been reading for over a century?

Black federal employees didn’t simply roll over and accept what was happening. They resisted and protested in ways that they could without giving the government cause to fire them. 20,000 people, including many employees, signed a petition of protest. There were mass meetings in Washington, but also in cities around the country. D.C. residents were not allowed to vote in federal elections until 1964, but protests in other cities were designed to get the attention of elected officials. Black churches played a significant role in organizing protests and speaking prophetically about the fact that all people are children of God. Once it became clear that the Republican party would not advocate for the Black employees, the then-new NAACP stepped up to take the lead. They were not able to get Wilson to back down, but the experience gave the NAACP a real boost, and it continues to work for equal rights today. It was a great disappointment that when Republicans took office again after Wilson’s second term, they left his racist policies in place, signaling that they no longer considered Black voters to be part of their constituency.

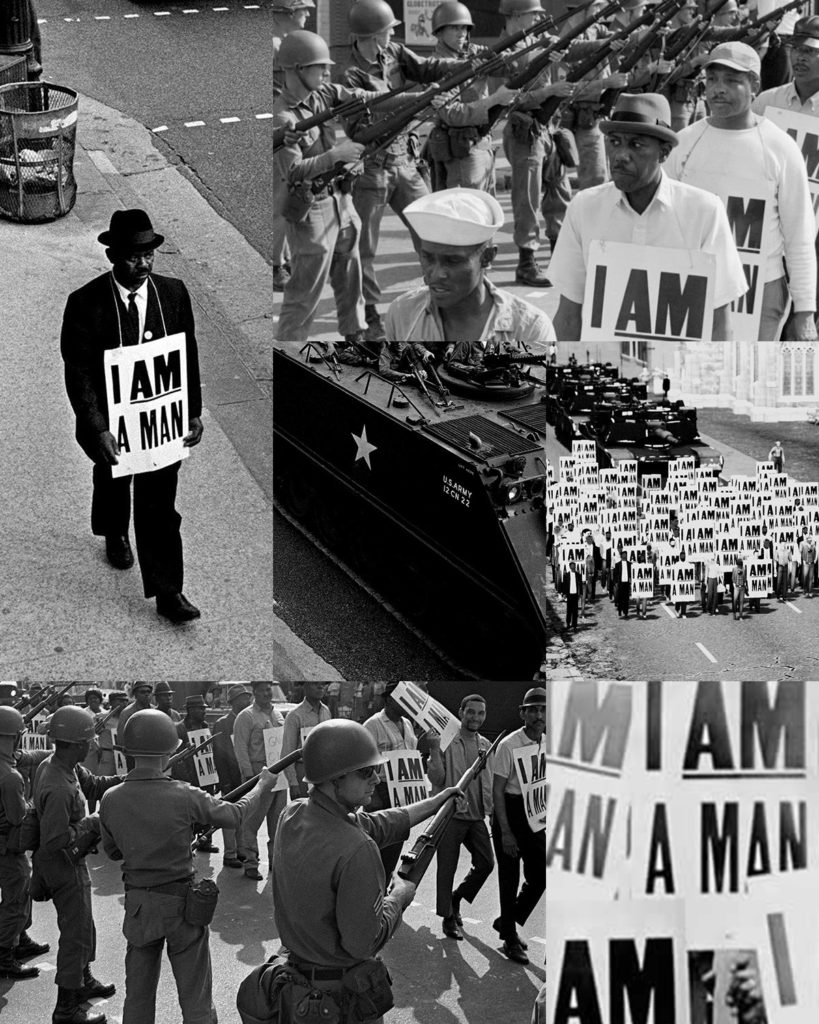

Fighting Back

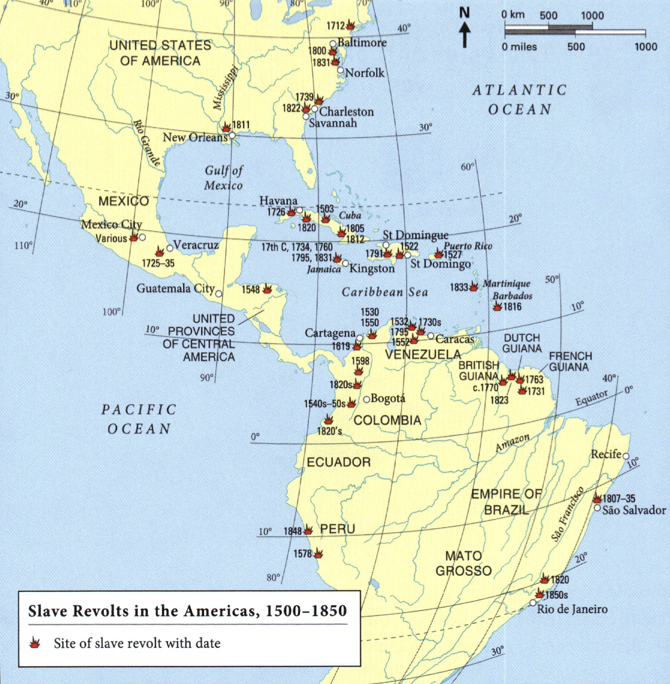

The resistance to Wilson’s racist policies is just one example among many of the ways Black Americans have fought for their freedom, their rights, and their dignity. It is an often-ignored part of Black History, but a running theme in Clint Smith’s Crash Course Black American History. It was present from the very beginning of European colonization. The San Miguel de Gualdape Slave Rebellion is an early example. It was the first documented slave rebellion in the mainland of North America, occurring in what is now South Carolina. According to a website devoted to abolitionists and anti-slavery activists, there are 65 recorded slave revolts in North America (and, we can assume, many more that were undocumented). Historian Bram Hubbell runs a website for teachers called Liberating Narratives. He offers information on rebellions by enslaved Africans, including the map below:

The Underground Railroad was another way that enslaved people risked their lives for freedom. The National Park Service has a list of many of the stations along the railroad that you can visit. The National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinatti is definitely worth your time, too. We’ve already noted the 200,000 Black soldiers who fought in the Civil War.

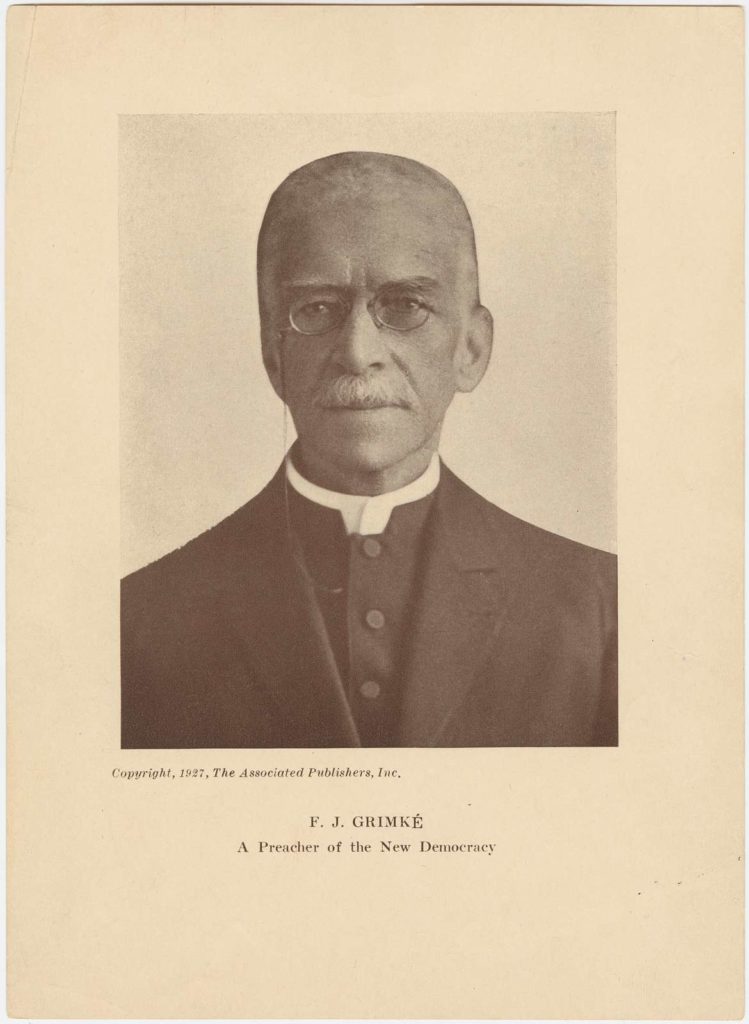

Many Black prophets spoke out against racism during Jim Crow. As we have noted, a very large portion of the White U.S. Church adapted itself just fine to the racist practices of that time. I’ve only recently become aware of Rev. Francis J. Grimke, a bi-racial13 Presbyterian minister who challenged the racism of his own denomination. He was a prolific speaker and author, and his collected works (edited by Carter G. Woodson) are available in Google Books. One of his sermons begins on page 523 of Volume I. In it, he takes the Presbyterian Church to task in a variety of ways, accusing it of preaching a sub-standard gospel because of its tolerance of racism. He was particularly unhappy that Princeton Seminary, which had racially integrated student housing when he attended, had decided to house Black students in a separate facility. (Perhaps it is no coincidence that Woodrow Wilson was the president of Princeton from 1902 – 1910.) I recommend the entire sermon, but I offer this particular paragraph as one of my favorites:

“Away with all this hypocrisy! Let us get down to bed rock, to fundamentals, to essential principles of Christianity. Let us have an evangelism, a straightforward preaching of the gospel that will keep off evangelistic committees, and out of theological seminaries, as students and as professors, men who are so unchristian as to be influenced by this wicked and contemptible spirit of race prejudice.”

Another example of resistance during Jim Crow: The U.S. exhibit in the 1900 Paris World’s Fair (Gates, 2019). Initially, it included nothing about African Americans. In response, Booker T. Washington contacted President McKinley and received a small sum for an “Exhibit of American Negroes.” W.E.B. DuBois put together an impressive collection of photographs of successful Black Americans, along with Black churches, Black libraries, Black universities, Black science labs, etc. The aim, obviously, was to present to the world—and the nation—images of Black Americans they may never have seen. The exhibit was a great success, receiving a total of fifteen medals.

We are a bit more familiar with Black resistance during the Civil Rights Movement, although most of us can’t name more than a small number of its leaders. Two of my personal heroes: Fannie Lou Hamer and John Lewis. Mr. Lewis was one of the college students who helped desegregate my hometown of Nashville in 1960 (Halberstam, 1998), so I am especially appreciative of his work. He later represented Atlanta in the U.S. Congress. His autobiography is outstanding (Lewis, 1998), and I recommend it to you. And I really like the way he would encourage young people to get into “good trouble” in order to push the nation along the path of progress.

Fannie Lou Hamer–well, what’s to say? She was a saint, a prophet, a warrior. She was a sharecropper born into extreme poverty in rural Mississippi in 1917, with very little formal education, yet she took on one of the most brutal racist systems in the land. She worked diligently for voting rights at a time and in a place when that meant putting her life on the line. She came to the attention of the nation when, in 1964, she attended the Democratic National Convention in Atlantic City to protest the seating of an all-White Mississippi delegation. This clip of her speech will be the best three minutes of your entire week—or your money back.14

Just two more heroes. The book Selma, Lord, Selma (published in 1997 and later made into a Disney movie) is the account of two children who participated in in the civil rights marches in Selma, Alabama, in 1965. Sheyann Webb was only eight years old and Rachel Webb was only nine when they decided to take part in the protest. I, too, was eight in 1965. I raised three children, all of whom spent an entire year being eight. And I simply cannot fathom how children that age can be so brave, so forward-thinking, as to sign up on their own to participate in such a protest.

Make no mistake: protesting was dangerous. Fourteen other Black girls who protested were imprisoned outside Americus, Georgia for 45 days—and their parents had no idea where they were. They were housed like animals in appalling conditions and they were lucky to come out alive. There’s a reason you don’t know about them: the Black History Month Story has white-washed the truth in order to minimize the violence inflicted on those who dared to demand that they be treated like human beings.

And finally, one example of contemporary resistors: The three women who coined the phrase Black Lives Matter and the organization behind it. They gave focus to the recent protests against police violence and other forms of racism. The Black Lives Matter Global Network Infrastructure is “adaptive and decentralized,” a vehicle for “organizing and building Black power across the country.”

Equally important are the millions of people who have stood up to racist people and undermined racist systems in the course of their daily lives. It has been my privilege to know many such people and my life is richer and better for their acquaintance.

FOOTNOTES:

- The slave trade is surprisingly well-documented, although information about individual enslaved people is scarce. Both sad and fitting, I suppose. There is a massive data base called Slave Voyages hosted by Rice University. It is highly interactive, with maps, videos, and numerous tools for learning about how more than 10,000,000 people were transported from freedom to slavery for nearly 400 years.

- John Casor sued in 1655 because he was being forced to continue working in spite of the fact he had completed his years of indentured servitude. He had served his time and earned both his freedom and fifty acres of farmland. Imagine standing in that courtroom hearing the judge declare that he would never own land and never be free. He is not lost to history; his story is preserved in the court records. Every American, every student in a U.S. history course, should know his name.

- Allen notes that one French observer of early American life was struck by the extreme poverty of many White people, noting that they had “little but their complexion to console them.”

- Actually, by some estimates, New York City had the highest number of enslaved people in North America, even more than Charleston. The story of slavery in New York is powerful, but not well-known. I recommend spending some time on the website based on an exhibit of the New York Historical Society called Slavery in New York. Or take a tour of the city to learn about the history of enslaved people.

- Traces of the Trade: A Story from the Deep North is a documentary about a Rhode Island family coming to grips with the role their forbears played in the slave trade—and the wealth they continue to enjoy as a result.

- My job was made possible by the money generated from Northern slavery. You can read about that here.

- Prof. Berlin offered a personal anecdote about how our slave society permeated life in ways we often don’t recognize. He grew up in the Bronx, near Van Cortlandt Park. “What I didn’t know was that it was probably once Van Cortlandt plantation and that there were slaves living and working there.”

- We often ask ourselves how people who saw themselves as good Christians could enslave other people. To answer that question, we can start by examining our own inconsistencies, the ways in which our attitudes and actions fail to meet our standards. We can’t explain our shortcomings accurately without confronting inconvenient truths, so often we just explain them away. There is no discrepancy, we argue, and then we use all kinds of rationalizations to convince ourselves and others that our personal virtues remain intact regardless of our behavior. How did slavery-supporting Christians do that? By arguing that slavery, far from being un-Christian, is in fact a Christian ideal. Theologian Stephen R. Haynes (2002) explains that many American Christians argued that the “races” invented in European colonialism actually were created and ordained by God from the beginning of time. Those arguments continue to be made today in defense of White supremacy. Some years back, I was talking to an adult education class at a church in my hometown about the role of race in politics. Toward the end of the hour, one gentleman asked how I could reconcile my beliefs with the “fact” that dark-skinned people were cursed when their ancestor, Ham, disrespected his father, Noah. I laughed, unfortunately, because I assumed he was being sarcastic. Not so. He believed he had rebutted any talk of racial equality by espousing a Judeo-Christian truth.

- We don’t hear much about them, sadly, but there were many women involved in the Civil Rights Movement in a wide variety of ways. Here are the stories of just some of the women involved in the 1956 Montgomery Bus Boycott.

- I also remember a student teacher we had in that class, a Black man whose name I don’t recall, who incorporated Black history into his lesson plans. When I got an unexpectedly low grade on a test, he pointed out that I got all the White history questions right and all the Black history questions wrong. I confessed that I didn’t study for the test because I thought I knew everything already. And that was true—for the White history I’d been taught every year up to that point.

- According to Princeton Historian Tera W. Hunter, while newly-freed enslaved people never received any compensation for their labor, some slave-owners did. President Lincoln issued an order putting an end to slavery in the District of Columbia in 1862. In order to maintain political support from those who had owned them, the federal government paid $300 for every enslaved person who was freed. According to online inflation calculators, that amounts to approximately $8,000 in 2023 dollars. On a much larger scale, in 1833 the British government borrowed twenty million pounds (40% the size of its annual budget) to pay British slave-owners in the Caribbean when enslaved people there were freed. That is the equivalent of 2.4 billion pounds today. The newly-free people, of course, received absolutely nothing.

- A Black professor I knew in graduate school told me of an old saying among Black Americans: “In the South, they don’t care how close you get as long as you don’t get too big. In the North, they don’t care how big you get as long as you don’t get too close.”

- Of course, by the standards of the day, Rev. Grimke was not biracial. The practice of hypodescent meant that he was, simply, Black.

- My apologies for the brief political ad at the end. I’m looking for a better video.