Before reading please be advised that this blog is an opinion piece on the constitutional referendum in Chile. It reflects my personal observations and research. To understand the process and key information, I received assistance from my Human Rights professor. I hope to share with you the powerful history of Chile from a learner's perspective. Additionally, please keep in mind that my sources have been translated to English for your understanding. Enjoy!

Since I was a young kid, history has been my favorite subject. Whether it was through school or family members, I was fascinated by the stories I heard and the ones left to my imagination. In high school, my curiosity developed into a deep admiration of cultures around the world. During my senior year, I took a course exploring global cultures and issues. I loved the class but was quickly confronted with how little I know about issues outside of the US. Although it was painful to admit, this realization inspired me to begin learning about global issues. I continued this journey throughout my first year at Hope and was challenged to venture deeper. I participated in programs, events, and discussions that analyzed the cultural and behavioral context of social groups. As I learned about other countries and navigated cultural diversity, I felt I was lacking a major element: experience. Towards the end of my freshman year, I declared a peace and justice minor and a social work major. Around the same time, I chose the “Politics, Social Justice, and Language” program in Chile. When I signed up for the program, I had no idea how it would encourage me to continue my journey of global curiosity.

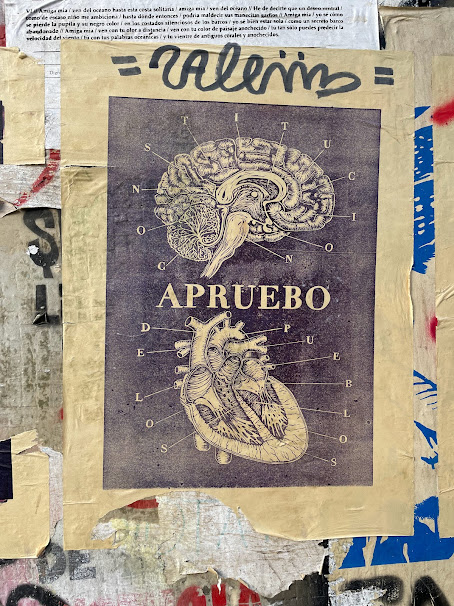

While I was abroad, on September 4th, 2022, Chile had a constitutional referendum to vote on a new constitution. The world watched closely as Chile created “The world’s most progressive constitution.” Although the proposal was rejected by 62% to 38%, I had the privilege of witnessing Chilean history firsthand.

Understanding the political climate:

The process for a new constitution began nearly three years ago after political tensions peaked and resulted in social outbursts throughout Santiago, Chile. The cause of these demonstrations? At the surface, it seemed an increase in the public transportation fare had inspired protests led by young students. But as millions gathered to express their frustration, they were demanding social reform. Chilean citizens face major social concerns such as: increased cost of living, low wages and pensions, and lack of access to quality public services. Over the past few decades, there have been debates over deep-rooted inequality and increasing social demands. There are different interpretations of the protests in Chile, but for most, the raise in public transportation was the last straw. Despite efforts to calm protestors, demonstrations quickly turned violent and the former president, Sebastián Piñera, declared Chile in a state of emergency. For the next few weeks protests continued and spread across the country. In an effort to restore social peace, representatives of nearly all political parties met to seek an agreement. About a month later, on November 15, 2019, the National Congress signed Acuerdo Por la Paz Social y la Nueva Constitución. The document outlines precise steps and a timeline for the creation of the new constitution.

Why a New Constitution?

The current constitution in Chile was approved in 1980 during the military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet from 1973-1990. Although it has undergone many amendments since it was introduced, there is a belief that it is outdated and insufficient in providing for public needs. However, counter-arguments have been made that these issues existed before the Pinochet era. In comparison, the proposed constitution would focus on balancing the distribution of power and meeting social demands. The document included 388 articles. In response to my question, “What are the main changes that will be implemented if the new constitution is approved?” My human rights professor highlighted specific social reforms such as:

- Multinationalism; recognizing indigenous and historically marginalized populations

- Equal gender representation in all domains

- Respect for nature and ecological economic development

- Responsibility of the state in matters of social rights (education, housing, health, work, etc.);

- Recognition of sexual and reproductive rights

- Decentralization or balancing of government powers, including the President.

Important Dates:

- In October 2020, Chilean citizens voted on two questions. The first: whether or not to create a new constitution, was approved by 79%. The second, what type of body should carry out the fabrication of a new Constitution? The elected assembly, a constitutional convention, was approved by 78%. For the first time in history, rather than elites or military powers, Chilean citizens had the opportunity to redefine their constitution.

- May of 2021, 155 constituents were elected for the constitutional convention. The institution would be the first in the world to equally represent men and women. In addition, 17 seats were reserved to represent Chile´s 10 Indigenous communities. The election and composition process was extensive, if you’re interested in learning more, visit the Constitutional Convention’s website.

- July 2021, the constitutional convention began drafting a new constitution. As stipulated by law, the convention would last a maximum of 12 months.

Bringing us to the present, where Chilean citizens would once again make their way to the ballot stations to cast their vote on the new constitution. Interestingly, all citizens are obligated to vote and those who do not could be fined.

Tensions were high leading up to the voting. The week of the election, my classmates and I received updates about protesting times and locations. *As foreign citizens, being caught in the middle of a protest is considered a terrorist attack against another government and would result in deportation. We were cautioned to avoid large crowds and carry our IDs at all times. On the day of the vote, most companies were closed due to the mandated holiday, but local businesses closed in preparation for the public’s response. No matter the opinion of the proposed constitution, it had been a long process and people were anxious about the outcome.

- September 4, 2022 With a 85% voter turnout, the constitution was rejected 62% to 38%.

After the voting booths were closed around 6 pm, the results were in and there was a clear rejection of the constitution. I felt strange as a foreigner in Chile when I saw the impact of this vote around me. I felt the emotions of so many and yet, the rejection did not directly affect me. In this I recognize my privilege, I will be leaving in a few months but for Chileans, this vote was a decision for their future. For some, it was a devastating loss after three years of hard work. Those represented for the first time in this constitution felt betrayed by the rejection. At the same time, others were relieved and threw grand celebrations. I empathetically watched the wide range of reactions from classmates, friends, and strangers. After the defeat, President Gabriel Boric made an address urging his citizens to “Valora a su Democracia que confíe en Ella para superar las diferencias y avanzar” (Value its democracy, trust that it will overcome the differences and move forward). He thanked the democratic process and citizens for participating in the electoral process which had the largest participation in Chilean history. In the past, President Boric has expressed an openness to repeating the constitutional process, but as of now, we are unsure of Chile’s next steps.

After reading about the protests that started this whole process, I was curious to learn more. My professor informed me “The current constitution recognizes the right to public demonstrations…However, there are laws that punish certain forms of demonstration.” While protests are a right granted to citizens, some acts are prohibited. For example, protestors are not allowed to barricade or burn objects in the streets that prevent vehicles from passing. This threatens the “libre circulación” (Freedom of movement)”. Article 13 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, grants citizens the right to travel and reside anywhere within the State or State of their choosing. In addition, protestors are banned from hiding their faces or throwing burning objects. If these laws are violated, federal and local authorities are legally authorized to intervene. Some believe this legal framework is loosely translated while others believe they are strictly enforced. As expected, I observed many protests the week following the rejection. Same as before, protests were led by young students wearing all black. Periodically, the Santiago metro closed as protestors filled the station but thankfully, they remained mostly peaceful. In the past month, I witnessed the passionate debate for human rights. While researching for this blog, I was fascinated by the precise language used to write laws. As I continue to learn about the political climate in Chile, I hope to explore a new interest: international relations.

For more information:

United Nations Human Rights Article on Chile´s Constitutional Process

Constitutional Convention Website

Opinion/Informational piece for foreigners