Water is life. Our liquid reliance is embedded in 70% of our world’s geography and makes up 60% of our bodies, after all. Yet, nearly one billion people do not have access to safe water.

Boiled down: One in eight people worldwide cannot find clean, drinking water.

And that’s exactly why the Hope College Engineers Without Borders (EWB-Hope) chapter traveled to Kenya in May 2017. Only 57% of Kenya’s population has sustainable access to clean water sources, according to the World Health Organization. By comparison, the United States measures 99%.

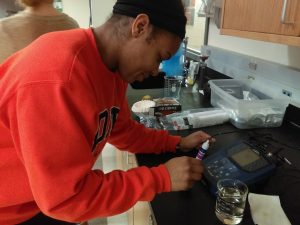

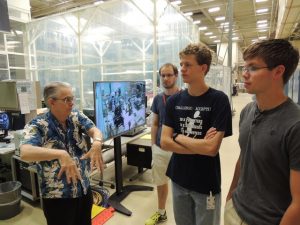

For three weeks, in a rural area called Bondo just outside Migori in southwest Kenya, Adam Peckens, laboratory director for the engineering department, and seven Hope students, coordinated and engineered the installation of two wells and a rainwater catchment system. Their efforts — financed through EWB-Hope’s own fundraisers and a crowd-funding program initiated by the College Development Office — ultimately changed the lives of over 500 local residents whose previous access to clean water was an hour’s walk, each way. EWB-Hope went on a mission to give water for life.

Their efforts ultimately changed the lives of over 500 local residents whose previous access to clean water was an hour’s walk, each way.

This was not EWB-Hope’s first trip to the Bondo area. The chapter — under the advisement of Dr. Courtney Peckens, assistant professor of engineering — has partnered with the community for three years and has made two previous excursions there — the first in 2015 to determine what water residents had access to (very minimal, very seasonal, and very contaminated); the second, in 2016, to attempt a well installation that unfortunately was not successful. This year, however, the team struck it water-rich. By the end of their stay, they watched their new Kenyan friends gratefully use hand pumps to access clean water close to home.

For all of the manual and mind hours it took to make living waters flow, none of the work hammered out by EWB-Hope in Africa or on campus prior to departure, was done for college credit. Instead the sheer satisfaction of knowing fellow human beings could now drink clean water was reward enough.

“It was a great learning experience where it’s not necessarily an equation you’re trying to solve for a grade like in an engineering class, but a real-life problem affecting real people.”

“It was a big success story for our students and the (EWB) chapter overall. They really pushed forward to get the work done,” says Peckens, an environmental engineer who worked on many different groundwater remediation projects around Michigan and the Midwest, before coming to Hope in 2014. “It was a great learning experience where it’s not necessarily an equation you’re trying to solve for a grade like in an engineering class, but a real-life problem affecting real people. It’s taking in all of the factors around that problem and trying to come up with the best solution. And that solution might not be perfect, but it works.”

To his point, Peckens recalls how designs changed once the team got on the ground in Kenya. Though the full drawing set and a mock build of the catchment system worked just fine in the engineering lab on campus, “when we got there, circumstances were different, of course,” he observes. “We lacked some of the same supplies or the right tools (we had back home), and multiple trips to the hardware store in Bondo meant we had to adapt the design in the field. It was a good hands-on experience for the students to see that not everything works out as you planned so how are you going to troubleshoot that.”

“It was a good hands-on experience for the students to see that not everything works out as you planned so how are you going to troubleshoot that.”

Another challenge was the language barrier. The Bondo residents speak Luo, a dialect of Nilotic languages. The Hope team did not have that language skill in their toolkit so dependence on their guide and interpreter, Paul O’lango, was heavy, especially at that Bondo hardware store.

“Part of our project requirements was to locally source as many components as possible,” explains senior mechanical engineering major Rilee Bouwkamp from Holland, Michigan. “For the rainwater catchment system built at a local church, this meant finding a 10,000-liter water storage tank, saw, gutters, nails, hanger straps, the works. Most of the frustration came with trips to the hardware store in nearby Migori that would take almost an entire afternoon. Trying to explain what we needed was difficult even with a translator’s help and a sense of urgency in Kenyan culture is rare. Overall, our team learned to be patient and we began to understand that this aspect of the project was out of our control.”

“In the process Hope students discover they have so much impact not just mechanically but in local relationships.”

Dr. Courtney Peckens has been EWB-Hope’s faculty advisor since she returned to Hope to teach in 2013. (And yes, Courtney and Adam are a husband-wife team.) A Hope graduate of the class of 2006 who participated in EWB herself (she travelled to Cameroon to install bio-sand filters), Peckens knows full well how much the program changes lives… and not just those who now are able to get clean water. “This program is a good fit for us. It ‘s a way for Hope engineering students to use their God-given talents to help people,” she says, “and in the process they discover they have so much impact not just mechanically but in local relationships.”

“My favorite memory of the entire trip was interacting with the community members because they showed me how to appreciate the little things in life,” concurs sophomore mechanical engineering major Kaytlyn Ihara from South Lyon, Michigan. “Compared to what we have in the United States, they have very little. Even though they don’t have the luxuries that we Americans have, they always had a smile on their face. They always were thanking us, but I can never thank them all enough for all that they showed me. Now being back in the States, it has really taught me to take nothing for granted.”

Now that clean, safe, reliable, living water flows in Bondo maintaining relationships is as important as maintaining systems.

EWB-Hope will continue to get updates from O’lango about once a week and then they’ll return to Kenya within the year, this time for a monitoring trip to check on the status of the wells and catchment system as well as the lives of their new friends. “We aren’t a group that comes in and installs an engineering system and then leaves without any future contact,” says Courtney. “We are in this for long-term solutions for people.”

Now clean, living water flows in Bondo. And so do beautiful, cross-cultural relationships. Both, it turns out, are necessities of life.

For one Hope College professor though, acknowledgment of the sacrificial nature and special identity of mothers goes far beyond matriarchal tchotchkes and trinkets. Influenced by her own spirited maternal role models, and after becoming a mother herself, Dr. Deb Swanson, professor of sociology, delved into how women define good mothering practices in their roles as either

For one Hope College professor though, acknowledgment of the sacrificial nature and special identity of mothers goes far beyond matriarchal tchotchkes and trinkets. Influenced by her own spirited maternal role models, and after becoming a mother herself, Dr. Deb Swanson, professor of sociology, delved into how women define good mothering practices in their roles as either