Ah, spring break in the Bahamas. Sun. Sand. Palm trees. Snorkeling in coral reefs. Exploring limestone formations. Visiting the town dump.

What? Wait. The town dump?

Yes, Deep Creek Town Dump to be precise.

For more than 20 years, Dr. Brian Bodenbender has had a penchant for teaching and researching coastal geology in the Bahamas, and the weather there has nothing to do with it. It’s all about the rocks, the sea and sustainability for Bodenbender, who has led more than 70 students to the Caribbean nation over the years.

On his most recent trip during Hope’s spring break in March, the geology and environmental sciences professor took seven more geology and biology students to, and through, a Bahamian island for a course called “Geology, Biology, and Sustainability on Eleuthera Island, The Bahamas.”

Along with showing off the geological and biological features of Eleuthera Island, Bodenbender also teaches about how sustainability efforts are, or are not, successful in a remote place where dependence upon natural resources is obvious every minute of every day. Eleuthera’s main industry is tourism, but many of its residents also rely on fishing and some agriculture, mostly mixed crops on small plots, for their living.

On an island that is long (approximately 100 miles) and thin (six miles at its widest part), all 8,000 Eleutherans depend on having 90 percent of their food imported which results in 100 percent of the waste remaining on the island. Thus the stop at the town dump. What Eleutherans do with that waste is one of Bodenbender’s lessons. He feels it’s worth teaching in a place that is both a tropical paradise for tourists and also a permanent residence for thousands.

“One of the aspects of being on an island is that it is expensive to ship stuff onto it and it doesn’t pay at all to ship stuff off,” explains Bodenbender. “So the ways that they handle household waste is to take it to the dump, which is maybe an acre or so with signs saying, ‘Please dump at the back.’ So whatever trash is taken there is thrown in a pile and then about once a week, they come by and light a match to it.”

Open-air incineration in paradise is an issue in and of itself, but the students also learn that the composition of Eleuthera’s bedrock creates another problem when it comes to burning trash. Since the island is mostly composed of limestone with little topsoil, the porous nature of the ground means that rainwater percolates through the dump’s ashen toxins right down into the groundwater and that toxic tea eventually reaches the ocean.

“So it’s quite obvious that this is not a great way to handle waste,” says Bodenbender, “and it’s not sustainable in the least. It’s an eye-opener for students and I hope it gives them a new regard for regulations. In this case there is a regulation, but that regulation is ‘Move this stuff to the back of the dump.’ That’s not a regulation that is going to protect the potential drinking water or protect the reefs that are offshore that may have toxins washing out into them. So it’s just a really, really stark contrast between life on an island nation and life in the U.S.”

Junior geology major Jacob Stid agrees and actually sees a connection between what he now knows of waste disposal on Eleuthera and waste disposal in the U.S. It’s not a favorable connection, though, for his home country.

“Here in the U.S, we think that because of our size and power that we are exempt from these problems. We are not as different as we perceive.”

“Over the course of this trip I came to the realization that, in a way, we live on our own island here in the United States,” says Stid, whose hometown is Mason, Michigan. “Let me break that down. On Eleuthera, resources are limited and care must be taken in every use of every resource including the disposal. Without such care, not only would resources deplete but also what remained would lie in ruin and contamination. Here in the U.S, we think that because of our size and power that we are exempt from these problems. We are not as different as we perceive. Although the effects occur more slowly, our neglect for how we use and dispose of our resources may even put us below Eleuthera from a sustainability standpoint.”

Bodenbender says Eleuthera is not without good sustainability efforts. And, he does show his students their successes, such as the making of biodiesel fuel from used cooking oil retrieved from cruise ships, as well as producing excess wind and solar energy that goes right back to the Bahamian government’s power grid. Those sustainability priorities are potential money-savers for the tiny island; waste disposal is anything but.

Prior to departing for their intensive spring break lessons on Eleuthera, students meet once a week with Bodenbender for this semester-long course to learn how to identify certain invertebrates and geological features they’d encounter on the island while there for eight days. Besides their sustainability excursions, the class also took day hikes in the island’s tropical forests and along its rocky coast, and went snorkeling to investigate coral reef degradation and rebirth.

“They were going to be seeing so much that is new, I wanted to teach them about these things (at Hope) before we entered the environment,” he says. “And it’s an environment that can be pretty harsh — with sharp rocks, even sharp plants and bugs if you’re not on a groomed beach. And we are not laying on the beach.”

Bodenbender headquartered his class at the Island School in Deep Creek — a private secondary school on the island that also is home to graduate-level research — for both living and teaching accommodations. After each exhausting day out learning on the island, class members would debrief at the school and write in journals. Now back at Hope, each student is turning their journal into a field guide of Eleuthera as well as writing a reflective paper on sustainability.

“It deepened my knowledge of the complex factors involved in ecosystems anywhere and how one can be better understood by looking at the other.”

For senior biology major Kristin Godwin, this course was an opportunity of a lifetime, and it deepened her understanding of the interdisciplinary scientific nature of the Bahamas. While she believes she’ll forever remember the indescribable, show-off-blue water and sky on Eleuthera, and that small fish that swam under her for protection as she snorkeled reef to reef, Godwin was also impressed by the complexities and challenges of sustainability in the Bahamas and at home.

“For me, the most important thing I learned was the relationship between biology and geology and their necessary balance within sustainability efforts,” says Godwin. “I was the only biology major on the trip, so I learned a lot about geology. And as I learned, I began to see the relationship between the two. It deepened my knowledge of the complex factors involved in ecosystems anywhere and how one can be better understood by looking at the other.”

The possible solution?

The possible solution?

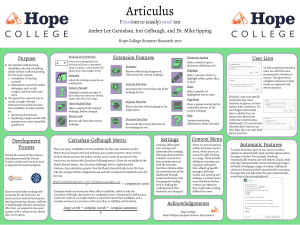

Besides working with closely with Dr. Jipping and Dr. Pardo, Carnahan and Gelbaugh also meet with their Black River clients every two weeks to discuss the app’s progress. From prototype to the (mostly) finished project, the feedback has been positive, says Jipping. And not only from Black River. The 2017 Consortium for Computing Sciences in Colleges (CCSC) Midwest was also impressed. At their recent 2017 conference, CCCS honored Carnahan, Gelbaugh, and Jipping with the best poster award.

Besides working with closely with Dr. Jipping and Dr. Pardo, Carnahan and Gelbaugh also meet with their Black River clients every two weeks to discuss the app’s progress. From prototype to the (mostly) finished project, the feedback has been positive, says Jipping. And not only from Black River. The 2017 Consortium for Computing Sciences in Colleges (CCSC) Midwest was also impressed. At their recent 2017 conference, CCCS honored Carnahan, Gelbaugh, and Jipping with the best poster award.