Since the summer of 2018, 42 Hope faculty members have ventured away from the college to do what they encourage many of their students to do — study abroad. Each professor took part in a unique, faculty-only Hope College program that instills the same benefits as students who study abroad receive: empathy, education, personal development, and cultural introductions, interactions and understanding.

The Hope Portal to the World program was created by Dr. Deirdre Johnston, Hope’s interim associate dean for global education and professor of communication, as was the GLCA Global Crossroads Innovations Grant she wrote to secure funding from the Mellon Foundation. Dr. Annie Dandavati served as co-director to help implement the grant in 2018.

Johnston says the program’s purpose is to increase cultural competencies and inform teaching and scholarship for Hope faculty members, and she believes it’s been working.

“Through the Portal to the World program, faculty teams bring back compelling stories that connect Hope College’s mission with people and institutions in 10 different countries, on three continents.” — Dr. Dede Johnston

“I see Hope College’s global strategy as cultivating compassionate action, grounded in ethical, community-based relationships, and authentic understanding,” explains Johnston. “Our mission is tied to our realization that our ‘neighborhood,’ that Christ commands us to love, extends well beyond our family, our community, or our nation. For students and faculty alike to live into that mission, it helps to have a compelling story to share – a story promoting dignity, justice, equity, and compassion for all God’s people. Through the Portal to the World program, faculty teams bring back compelling stories that connect Hope College’s mission with people and institutions in 10 different countries, on three continents.”

As for some of the faculty members, they say their two-to-three week Hope Portal to the World experience has helped them. Here’s how:

“Chinese hospitality and their attention to detail were impressive. Most of us were strangers to our hosts, yet they showed us the utmost kindness and received us as friends. In addition, every detail was coordinated, and this helped us focus on developing relationships with our counterparts at the various universities and finding common interests for scholarship. I am hopeful that these relationships will lead to future student exchanges between Hope College and Chinese colleges/universities as well as educational research that compares learning and affective outcomes between countries.” – Dr. Stephen Scogin, on the “Hope Faculty in China” study tour

“I appreciated hearing from a variety of different people about their experience with Christian faith and Kenyan and African culture. Several students told of how sometimes too rigid a Christianity can interfere with African culture, and a faculty colleague who was a Catholic nun related how often a too-relaxed attitude toward African traditions on the part of some African and Church authorities can interfere with development efforts inspired by the Gospel that protect human rights. Overall, I was just impressed with how vibrant the experience of the Christian faith was there.” – Dr. Jack Mulder, on the “Engaging History, Politics, Health, Religion and Ecumenical Higher Education in the Kenyan Context” study tour

“Focusing on the ancient worlds of Greece and Rome while traveling with a classicist — what could be better? And that classicist, (Hope professor) Stephen Maiullo, is a wonderful teacher. On top of that, at every meal all of us on the trip had engaging and stimulating conversations — about the day’s events, pedagogy, politics, religion, you name it. It was a great way to get to better know my colleagues away from Hope. – Daina Robins, on “The Body through Sport, Art and Theatre in Ancient Greece and Rome” study tour

“Food provided one foundation for my learning on this trip. Kimchi on fried rice plus miso soup for breakfast. Three courses of fresh fish at the fish market for lunch, including squid that squirted its ink as the skilled vendor prepared it for the table. Rice crackled and vegetables steamed as the bibimbap arrived, still sizzling, at our table for dinner. Shared meals provided opportunities for cultural immersion and deep conversation with my colleagues.” — Dr. Marla Lunderberg, on “Demystifying Complexities: Exploration into South Korean History, Culture and Sociopolitics study tour

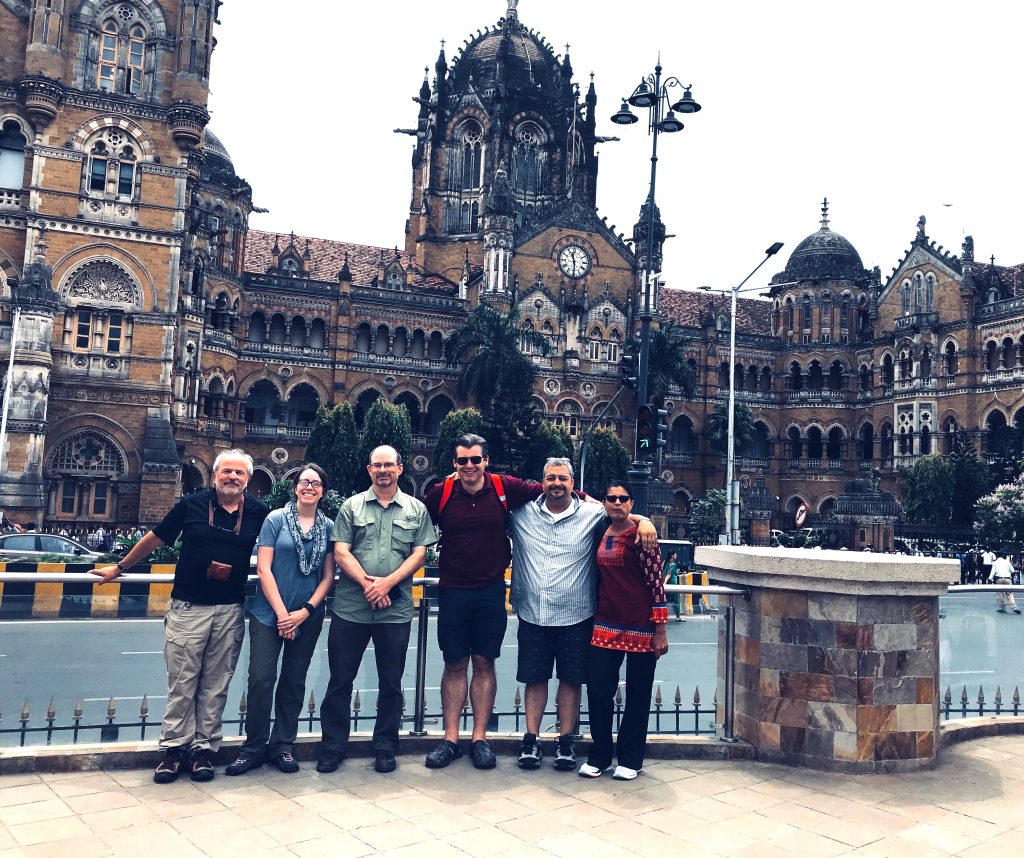

“Originally being from India and having spent a great deal of time there, it was interesting seeing India through the eyes of colleagues. And the more I see India through the eyes of my colleagues, the more questions I have myself. They raised so many good questions that I sometimes just did not have the answers. So, through this, I’ve learned that maybe we live in this stage of adaptability and flexibility. Not knowing with conviction what we know yet being convinced about it requires both flexibility and adaptability. I mean, I’m not a pushover but at the same time, giving room for intellectual expansion and enrichment is very important. It was lovely just to be able to take this trip and learn even more about myself and India in this way.” — Dr. Annie Dandavati, on leading the “Hope College/Flame University Liberal Arts Collaborative” in Delhi, India