Faculty Feature: Pliny was the Answer

Coming out of a class one evening I got a text from my wife: “Guess what the answer was on Final Jeopardy.” I replied, “Since I don’t know what the question was, I can’t know the answer.” She couldn’t remember the exact wording but it had to do with letters written by a Roman and it mentioned the death of his uncle, so the answer had to be Pliny the Younger.

She knew this because she’s heard me talk about Pliny for years. He wrote almost 250 letters, including two famous ones that describe the eruption of Mt. Vesuvius in 79 AD, which covered Pompeii and Herculaneum. Pliny’s uncle, Pliny the Elder, died in that eruption. A later letter tells the emperor Trajan how Pliny dealt with Christians in the province of Bithynia (part of modern Turkey) in the year 112. It’s the earliest non-Christian source we have about the Christians.

I became interested in Pliny in seminary and graduate school, more years ago than I care to recall. I have used his letters extensively in my research and academic writing, especially in my book, Exploring the New Testament World. Somewhere along the way, I began playing with the idea of writing a historical mystery set in ancient Rome. The main question was who would be my detective. Several writers—Lindsey Davis, Steven Saylor, John Maddox Roberts and others—write Roman mystery series that use fictional characters as their investigators. The more I read Pliny, though, the more I realized he had the skeptical, analytical mind that would make a good detective.

So, just as in Final Jeopardy, Pliny was the answer for me.

I like punny titles. The phrase “All Roads Lead to Murder” struck me as appropriate for a Roman mystery novel. That meant I would need to set my first novel at a time in Pliny’s life when he was traveling. In the spring of 81 AD he was returning from a year of government service in Syria. I found a small publisher that was interested, and off we went. That publisher put out three Pliny novels before the owner died. I was fortunate to find another small publisher right away, and the series now runs to six books, with a seventh due out this year.

I’ve been gratified by critical comments about the books. Library Journal said the second in the series, The Blood of Caesar, was one of the 5 Best Mysteries of 2008, “a masterpiece of the historical mystery genre.” One reviewer of the sixth book, Fortune’s Fool, said, “Bell reinforces his place among those who are pushing the mystery beyond genre, toward the literary.” I thought I was just telling stories.

I’ve been gratified by critical comments about the books. Library Journal said the second in the series, The Blood of Caesar, was one of the 5 Best Mysteries of 2008, “a masterpiece of the historical mystery genre.” One reviewer of the sixth book, Fortune’s Fool, said, “Bell reinforces his place among those who are pushing the mystery beyond genre, toward the literary.” I thought I was just telling stories.

All of the Pliny books are available online, along with my contemporary fiction and a couple of non-fiction books.

Student Feature – Noah Switalski

When I decided to pursue a history degree, I never expected to be able to experience history firsthand; however, I proved myself wrong by traveling abroad to Seville, Spain in the fall of 2017. There, and throughout my European travels, I visited museums and historic sites and greatly deepened my understanding of history and how it has impacted the world in ways that are not immediately obvious.

Seville is a city of around 750,000 people and is located in the south-eastern part of Spain, in the autonomous community of Andalusia, of which it is the capital. The city has experienced a tremendous amount of history, and all of it is evident in the structure of the streets and the buildings that remain. The city traded hands between the Romans, the Frankish Christian kings, the Omeya dynasty, and the Arabic kingdom of Al-Andalus and then the reconquering of the Catholic Kings in 1492. All of this rich history is on full display in the varied and fascinating architecture of the buildings and art museums. My experience as a history major allowed me to ask important questions when visiting such sites and to analyze the historical material offered, which was often biased in one way or another.

I was lucky enough to visit Rome while I was abroad, which was the crown jewel of my travels, as it contained many of the historical sites that I had been reading about since my childhood. The Coliseum, the Roman Forum, and the many museums and buildings all captured my attention in a way that I could never have anticipated. My historical knowledge greatly improved my visits to these sights, as I could allow myself to fully comprehend the significance of each location and to really enjoy the work of our ancestors.

History, both modern and ancient, has captivated me from a young age, and experiencing the sights of history textbooks was truly a marvel for me. The buildings I visited and streets I walked all served to deepen my appreciation for history. Furthermore, I took a history class at the University of Sevilla while I was abroad and therefore observed how history was taught in a foreign university. It was enlightening to see the differences between the American classroom and the Spanish classroom, as the treatment of subjects such as World War II and the social revolution of the 1960’s were handled in a vastly different manner. Even the small anecdotal information was different, as the common history assumed to be known was that of Spain, whose history stretches back much farther than American history – at least according to written textbooks.

I would recommend that all history majors travel abroad – the experience of living history by visiting famous and important sights of human heritage is invaluable, as is the experience of exploring a culture apart from that of the United States. Even if it is not possible to make the voyage as I did, visiting the historical locations in places that you travel to is a crucial and often underappreciated step in for historical understanding. History is everywhere, written or not, and to truly understand it, one must get out and explore it!

Alumni Feature: How to Answer “What are You Going to Do with That?”

If you are a student of history or simply the humanities in general, you get asked the following question A LOT: “So, what are you going to do with that? Teach?”

I’m pretty sure if I had a dollar for every time I was asked that about my studies in English and history, I would be wealthy by the grace of compound interest. I’m sure you would too.

I’m here to tell you that I’m a living, breathing case study of a humanities major who succeeded in heading straight into the corporate world and did not make a stop to graduate school (yet). I have a house and a dog and a retirement account. I’m doing just fine, without a “practical” college degree.

The condescension of that terrible “what-are-you-going-to-do-with-that” question plagued me all through college, and now when I think back, I could have spared myself anxiety over thoughts of myself as a starving artist, or worse — gasp — back working in retail forever if I had met people who had indeed skipped the graduate school route, made a way for themselves in the working world, and also fit my standard of a functioning adult.

So, what will you do with that history major or minor? Or any humanities major or minor for that matter?

You will write well.

Do not underestimate the power of good writing. Seriously. Most of what happens in the work world is now done through the written word. No, it’s not 50-page research papers. It’s email or instant message or blog posts. Being able to clearly communicate is an invaluable skill and you’ll have it.

You will be able to persuade.

Back to writing. I work in marketing so persuading is an important part of my job function. However, it doesn’t matter where you are in the work world, if you can persuade and influence others to take an action, to help you, to not make a terrible business decision, you are winning. Persuasion is part of constructing a thesis, and guess what? Those pesky emails or presentations are thesis statements!

You will be able to speak in front of others.

Maybe I’m biased, but I truly believe that communication is key to success in most jobs. No matter where you work or what job you do, you’ll probably have to speak in a meeting or present a case to your boss. Your training as a historian has included presentations and discussions. Now–thanks to your professors–you can walk in a little more confidently and contribute in a meaningful way.

You will have an understanding of the ramifications of an action.

History majors have amazing critical thinking skills. Critical thinking is scarcer than you realize in the workplace. And you’ll not only use it there, but also, more importantly, in your personal life. You’ll see the big picture while still understanding how everything all fits together. Being able to look to the past for clues and insight regarding the present and future is what historians are trained to do. This skill will help you reflect on your own journey and help you make decisions about where to go next. In that way, I think historians are some of the most resilient people in the world, granted they translate their academic skills to their personal and professional life.

So you may not know all the business jargon or how to write a marketing plan or how to schedule an Outlook meeting. But you’re a liberal art student, so you can learn.

In a world where everything is becoming more interdisciplinary, where everything continues to becoming more connected, we need people who can see beyond the code or beyond the robot. And that’s where you come in. Don’t think that because you aren’t training for a job right now that you can’t or shouldn’t end up working at one. We need the historians in the archive and in the classroom, of course. But we also need them to bring a set of unique perspectives and skills to other professional fields.

If anything, remember that the greatest gift of your liberal arts education is that of being a lifelong learner. Necessary professional nonsense aside, your ability to ask good questions, to seek truth, to solve problems, and to come to your own conclusions will continue to serve you well. I’m grateful for my education being just that, an education, not training for a job. For that, my life is all the richer, and yours will be too.

A Bittersweet Goodbye

Happy New Year, and welcome back to Hope students, faculty, and staff!

Happy New Year, and welcome back to Hope students, faculty, and staff!

The history department is gearing up for our semester, including offering new courses on Russian history and the history of peacemakers in the 20th-century United States. All of our faculty are looking forward to meeting new students and working with them on a great variety of research projects.

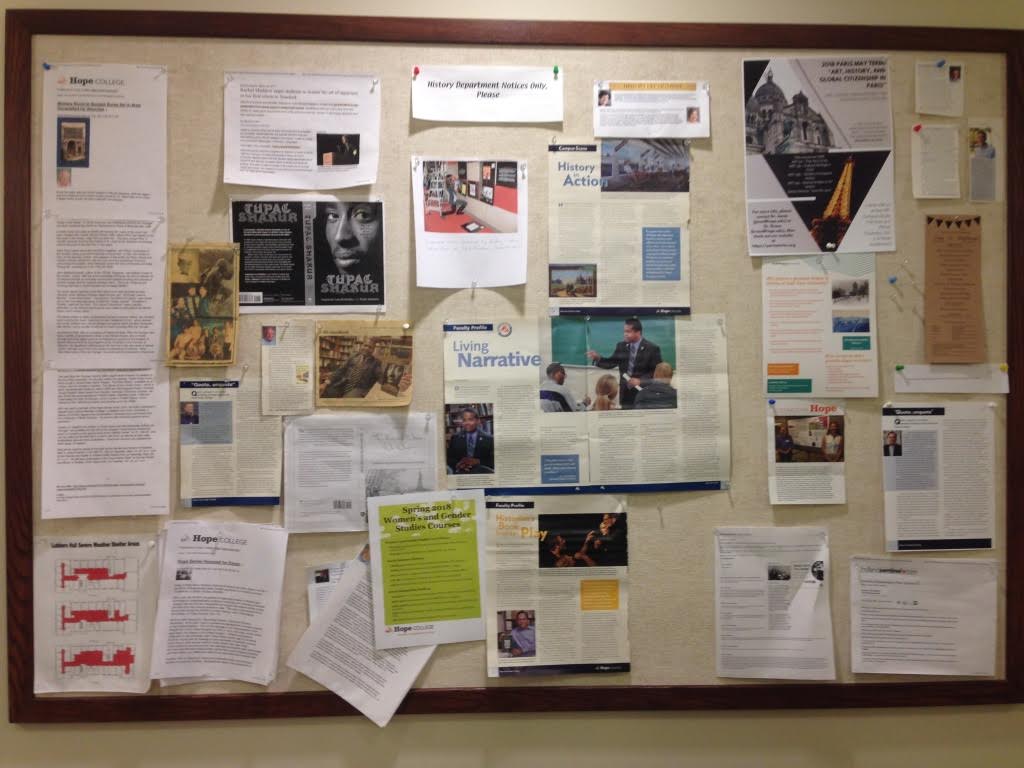

But this semester we are also saying goodbye. The hodge-podge bulletin board in the history department area on third-floor Lubbers is going away in a few weeks.

All the faculty in our department have a soft spot for this bulletin board. Over the years, we’ve put up random pictures, articles, and notices, and we’ve rarely taken things down. It has become a kind of primary source–a visual and documentary history of chance events from the last eight years or so. In the interest of archival preservation, here are a few of my favorite things on it:

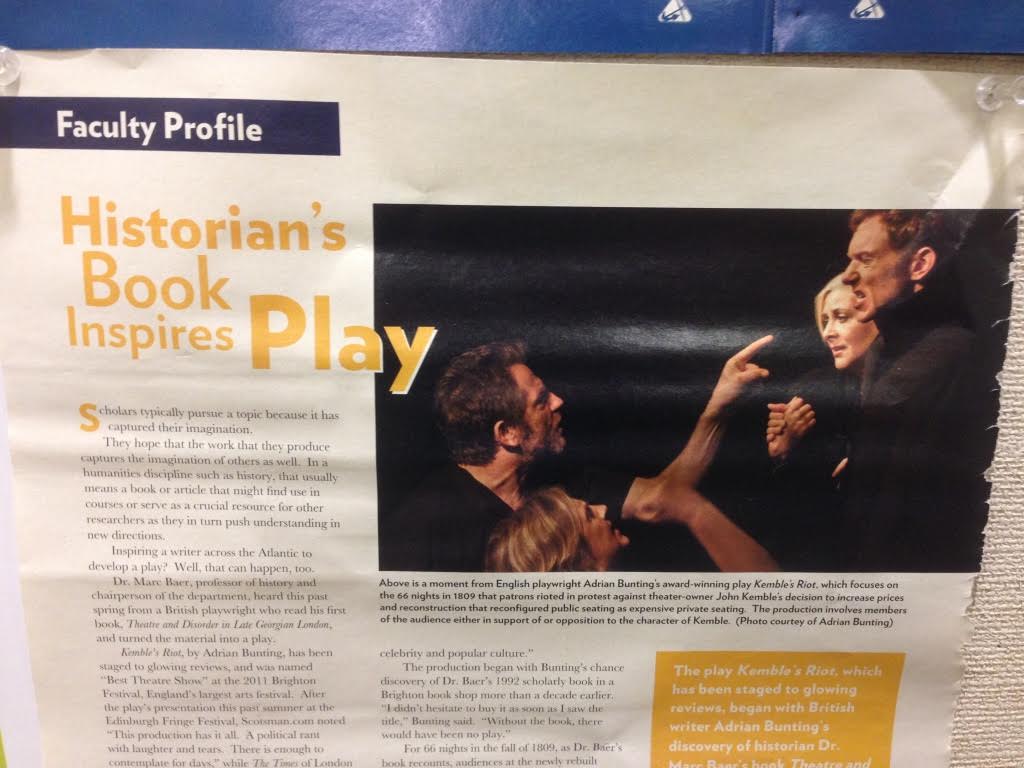

A News from Hope article about how a playwright based his Scottish Fringe Festival play on a chapter in Dr. Marc Baer’s book dealing with a London theater riot.

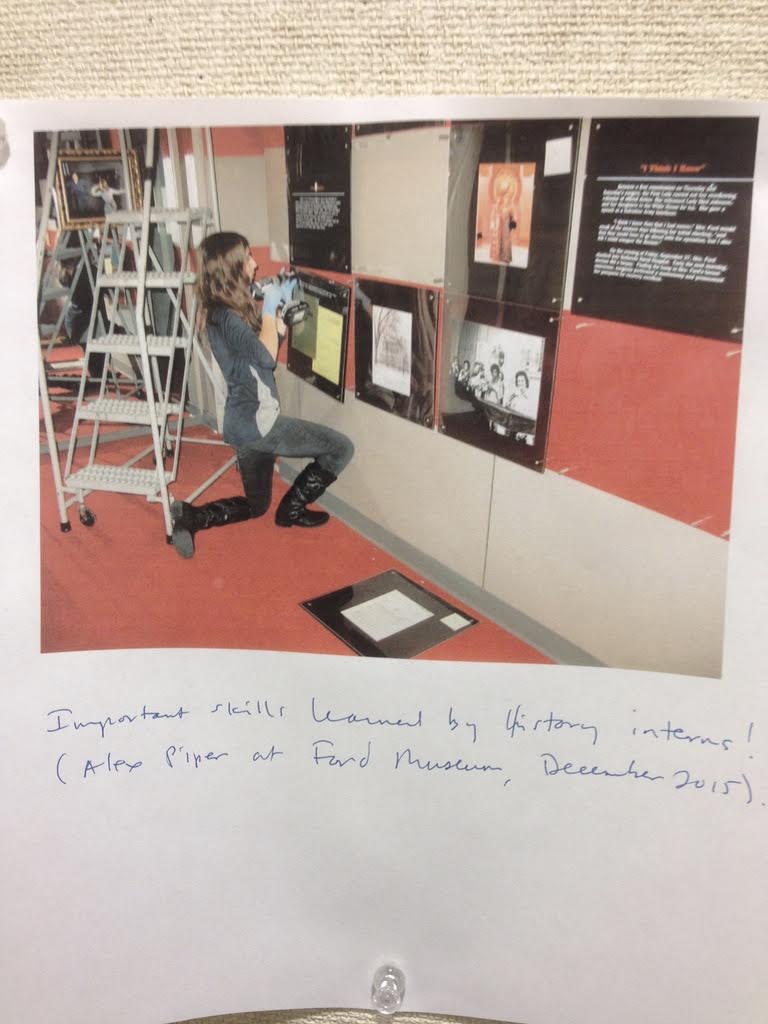

A picture of alumna Alex Piper installing an exhibit at the Ford Museum, with a hand-written description in Dr. Baer’s almost-impossible-to-read handwriting.

A press release about Dr. Albert Bell’s 2013 book about Pliny the Younger solving a murder mystery in the ashes of Mt. Vesuvius.

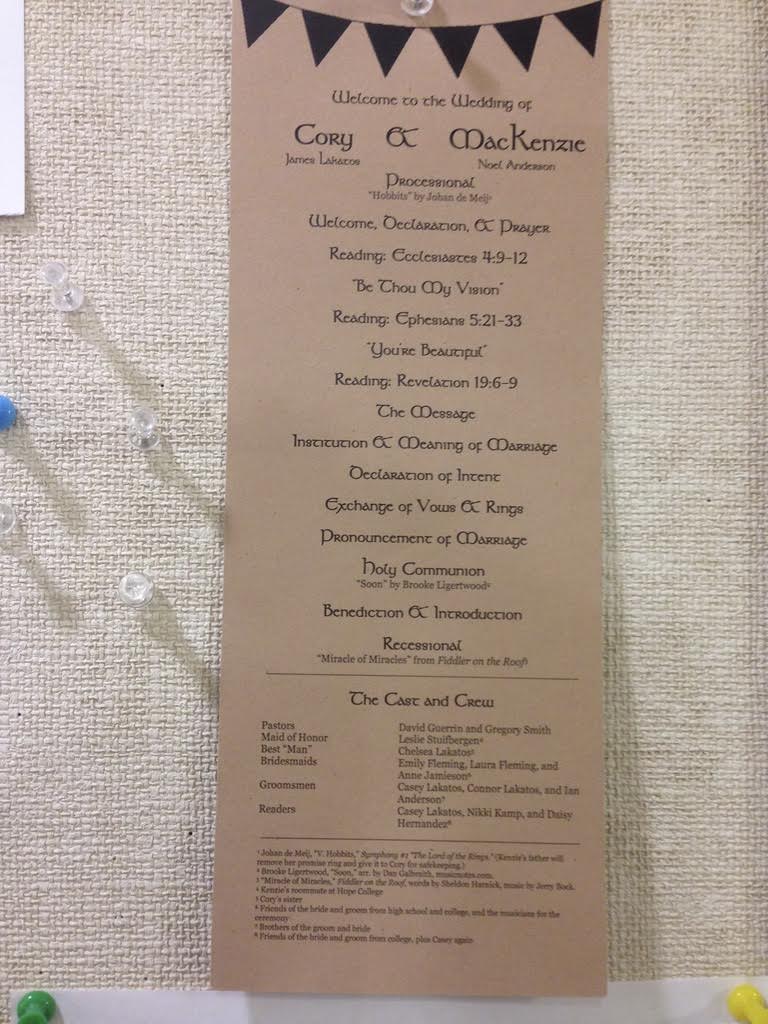

The 2014 wedding program of alums Cory Lakatos and MacKenzie Anderson(complete with footnotes! Turabian rules!)

An advertisement for the Utah State history department. Why?

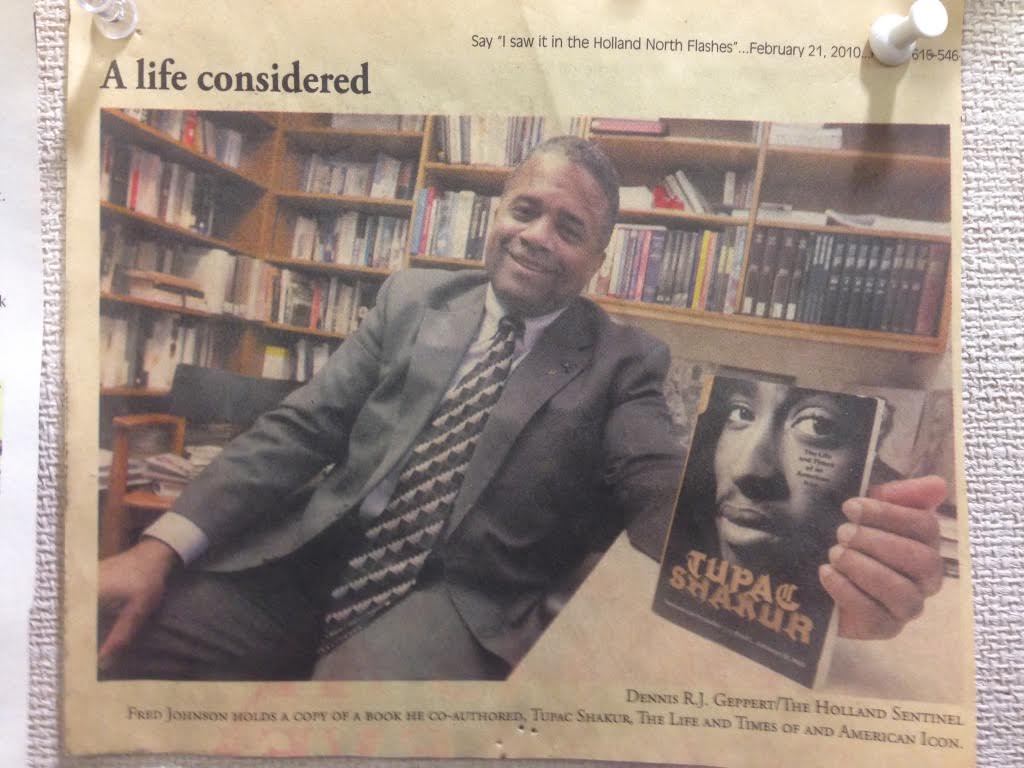

A Holland Sentinel picture of Dr. Fred Johnson when he was being interviewed about his 2010 book on Tupac Shakur.

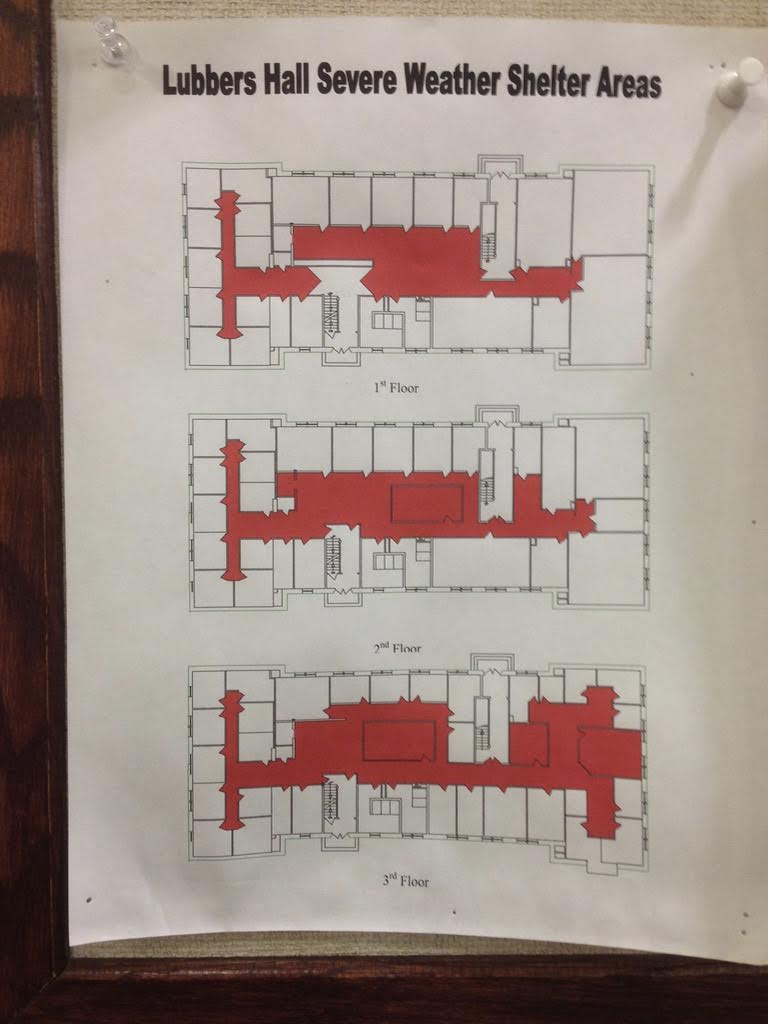

A map of Lubbers Hall severe weather shelter areas. Fortunately, we’ve never had to use this.

And finally, the printout of the cover of my book, The Men and Women We Want. I still remember my excitement when my publisher sent it to me, and I immediately printed it out and slapped it up there.

And finally, the printout of the cover of my book, The Men and Women We Want. I still remember my excitement when my publisher sent it to me, and I immediately printed it out and slapped it up there.

We will definitely miss our bulletin board full of random moments from our past. But we are excited that our awesome office manager, Raquel Niles, will be creating a new display that shares stories from our blog on the theme “What Can You Do with a History Major?” In the meantime, you have a few more weeks to come take a final look before it all goes away.

The Gifts of the Season

It’s the end of the semester. This is one of those good news, bad news stories. The holidays are coming. We are about to get a break. For some people, the holidays mean a chance to see friends and family. For others, the holidays can be a challenging time, with loneliness and depression always a danger. As a teacher, I am (like my students, I think) a little tired after the rigors of the semester. August seems a long time ago. Final deadlines for classwork loom on the horizon, and my students have begun to look a little bit tense and weary. And it gets dark so early!

It’s the end of the semester. This is one of those good news, bad news stories. The holidays are coming. We are about to get a break. For some people, the holidays mean a chance to see friends and family. For others, the holidays can be a challenging time, with loneliness and depression always a danger. As a teacher, I am (like my students, I think) a little tired after the rigors of the semester. August seems a long time ago. Final deadlines for classwork loom on the horizon, and my students have begun to look a little bit tense and weary. And it gets dark so early!

For me, the bad news is that the work my students and I did to become a community in each class will be over. We won’t see each other weekly, or talk about ideas together. The shared interest, the trust, and (for my students) solidarity in the face of adversity (that’s me, sometimes) won’t be the same next semester. New semesters are new beginnings, and for that I’m grateful, but I will miss the old semester and the relationships we built during the past months.

The good news is that I can see what my students have accomplished. This fall, I am teaching the history capstone seminar, an advanced history course requiring a research paper, and a first year seminar. I also advised nine candidates (students and alumni) who submitted Fulbright applications in October. In both the Fulbright process and all of my classes, the joy of the end of the semester is seeing my students accomplish what they set out to do. Some of them will write brilliant papers. Some of them will write longer, more complex papers than they have ever attempted before. Some of them are writing in new genres—personal statements; grant proposals; analytical papers instead of reaction papers; history papers, when their majors are not history; arguments supported by evidence instead of simple opinions. They are challenging themselves, and it is a privilege to be a part of their efforts.

I will read all the papers with care and with excitement. I celebrate when a student finds a primary source that makes her argument come to life. I admire the breakthrough when a student who has been summarizing other historians’ arguments makes a clear argument of his own. When a student writes a clear argument supported by evidence for the first time, I cheer. I am in awe of the work my students have done in my classes, when I know they have other classes, co-curricular activities, jobs, and lives beyond the classroom. I look with admiration at my first-year students, who have made the transition to college, and who are moving on to learn more about themselves, their talents, and their goals. I have my fingers crossed for my Fulbright students, who will find out in January if they are semi-finalists. There is a lot to celebrate at the end of the semester. I want to thank all my students, without whom my days would lack purpose. Thank you for your work, your trust, your good will, your persistence, and your cheerful attendance and participation. I think I had record good attendance this semester, and I take it as a sign that you were with me, and we were accomplishing something worthwhile.  I wish you all a very Merry Christmas, or Happy Holidays if you celebrate something else. I hope the end of the semester is a good one for all of you, and I hope the New Year brings you all manner of new joys and new adventures.

I wish you all a very Merry Christmas, or Happy Holidays if you celebrate something else. I hope the end of the semester is a good one for all of you, and I hope the New Year brings you all manner of new joys and new adventures.

Alumni Feature: Claire Barrett, ’15: “Do What You Love”

I grew up in a family that loved history. As a child I would attempt, in vain, to keep up with my father and older sister at dinner as they jumped from topic to topic, war to war. Tired of not contributing, I began to read. What began as an earnest desire to be part of my family’s dinner conversations became a lifelong passion. History has been and is a central point within my family. My first real conversation with my grandfather was on the topic of William Manchester’s semi-autobiographical book, Goodbye, Darkness. History not only influences the way I view the world, it is also a very real link to my family. Because of this, I grew up loving and respecting history, and in particular, military history. It enthralled me like no other subject could, and so, despite many well-meaning “what are you going to do with a history degree?” questions, I pursued a history major.

Thus, I graduated from Hope with a degree in history and then a MA in the History of War from King’s College, London. In college, I had no real clue what I wanted to do with my degree, and to be honest, I had no real idea in graduate school either. I just knew that I wanted to work in some capacity in or around the subject of history. My introverted self-delighted in the hours spent in the stacks, and in the British National Archives. Yet despite the welcome solitude, my degree path also gave me countless opportunities, from interning with the U.S. State Department in London during my time at Hope, to working with a NY Times bestselling author while at graduate school in London. A history degree can seem niche if you let it. However, as I found out, there are always places in the work force for curious, critical thinkers who know how to do serious research. My current job is a product of that.

I landed my job as the associate editor for MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History and Military History magazine because of my work while in London. I am lucky that I get to engage in the material that excites me the most every single day.

My sister Esther Barrett Wloch (’12), another Hope College history major alum, went in the opposite path of me. She worked for several years at the University of Michigan Musical Society and now currently works for Duo, a cybersecurity firm. She is thriving, despite having no background, I mean literally zero background, in the tech world due to her strong analytical and communication skills that she sharpened from her studies of history.

To be a historian, one engages with current events with a critical eye and a deeper understanding of that history, whether it be political, social, or military. The somewhat tired and oft-repeated line by George Santayana “those who do not remember the past are condemned to repeat it” still rings true today. For, as Churchill’s biographer Manchester wrote, “history is more than a time line, more than the sequencing and parsing of collective memory.”

My father, a musician (someone who has followed his own somewhat unique path), always said to me, “Honestly Claire, do what you love, work hard at it, and it will come together.” So that is my advice, and it is simple: Do what you love, for a degree in history means to have a thorough knowledge of the past, which cultivates one’s intellect, teaching one to know how to think, not what to think. The nurturing of one’s mind is invaluable, and trust me, imminently transferable to the world of work.

Student Feature: Jennifer Cimmarusti

The application deadline for the Paris May Term is Nov. 29. As that date approaches, Professor Janes asked senior history major Jennifer Cimmarusti to share some of her experiences and insights about the trip.

Professor Janes: What was your favorite place that you visited or activity you did?

Jennifer: The first was the beautiful town of Versailles, which we visited together as a class. While most people are interested in the main palace where the kings lived, I was personally more fascinated by the smaller mansions and the lush gardens that surrounded each building. To see the incredibly detailed designs of the buildings and extravagant furniture was a once in a lifetime opportunity. Along with that the places were full of fascinating history. As someone who absolutely loves the French Revolution, it was a dream come true to see the Jeu de Paume, or tennis courts, where the National Assembly met and planned their revolt. Overall, Versailles was my favorite place that we visited as a group.

Professor Janes: What surprised you about Paris?

Jennifer: I was surprised at how well I was able to communicate with Parisians. As someone who does not speak a lick of French, I was quite nervous about how I was going to get by. However, I found out that most French people do speak English, and I was able to pick up some French phrases. When all else failed, hand gestures worked as well. So what I thought was going to be a major issue was actually one of the easier parts of the trip. It also taught me that it is okay to travel somewhere and not completely understand the language, though a few words or phrases can’t hurt.

Professor Janes: Can you describe an example of how history shapes the city?

Jennifer: One of the aspects of Paris I found most intriguing were the subtle hints of history located just about everywhere. It was hard to go anywhere in the city and not be surrounded by centuries of history. Even the streets themselves had a story to tell. In the mid-19th Century under the rule of Napoleon III, Baron Georges-Eugéne Haussmann was instructed to carry out a massive urban renewal plan. Not only did this modernize the city, but it also helped with sanitation and overall cleanliness. One of his most important projects was widening the streets of Paris and to create new apartment buildings. A prime example of his work can be found on the famous Avenue de l’Opéra, the street leading up to the Garnier Opera House. Here one can see the simple architectural style that was used by Haussmann and the wide streets to allow both pedestrians and cars through. So when I say that every aspect of the city is covered in History, I literally mean every part of it.

Professor Janes: Any advice for students considering traveling on May or June terms abroad?

Jennifer: My best advice for those considering studying abroad is do not put it off. While you may be hesitant for one reason or another about traveling abroad, it is also good to consider the reasons you should go. For instance, while I love to travel I was incredibly nervous about going to a foreign country by myself with no friends or family to accompany me. It was not until I talked to you, Dr. Janes, that I began to realize the importance of studying abroad. I remember you told me that not only is it vital to my own education, but also when else in my lifetime will I be able to do something like this? So I want to encourage those students out there who were scared like me to have a little faith and take that step forward. Traveling abroad has been one of my best experiences and I would do it again tomorrow if I could.

Faculty Feature: Marc Baer

Historians don’t create information: they read what’s handed to them, or rather what they can discover that was created by people in the past. Often, one bit of information contradicts another, and the historian is forced to compare and then choose between them, or ascertain which data are the truest, or construct a narrative from the disparate, contradictory bits. Beginning with our undergraduate years, we do this over and over until what begins as a method of analysis becomes second nature to us. We use it when we engage in scholarship, but also in our lives as citizens when we read newspapers, listen to speeches or watch television news reports. The world calls it critical thinking; historians call it being a thoughtful historian.

Historians don’t create information: they read what’s handed to them, or rather what they can discover that was created by people in the past. Often, one bit of information contradicts another, and the historian is forced to compare and then choose between them, or ascertain which data are the truest, or construct a narrative from the disparate, contradictory bits. Beginning with our undergraduate years, we do this over and over until what begins as a method of analysis becomes second nature to us. We use it when we engage in scholarship, but also in our lives as citizens when we read newspapers, listen to speeches or watch television news reports. The world calls it critical thinking; historians call it being a thoughtful historian.

Now, imagine yourself as head of HR in a company, or the owner of a small business, or perhaps a dean employed at a prestigious small college in the Midwest. When you’re not signing forms, most of your time is spent doing precisely what the historian does. Hence my thesis (which, by the way, probably should have appeared in the previous paragraph): the best training for someone who is an administrator is—trumpet flourish here—history!

My argument is rather simple. In any workplace setting where one is called upon to make decisions—involving two people whose stories challenge each other, or two options presented to you either of which, if implemented, will make someone angry—the historian’s method kicks in. It’s not so much that we’re perpetually skeptical—which I would argue is an unhelpful attitude—but perpetually curious, inquisitive and aware that most contexts are characterized by complexity rather than simplicity. Therefore, when we’re in this analytical moment, our minds go to, “Hmmm. I wonder.” We begin to turn things over, to step back from the context, to seek antecedents, and to compare the situation with others we have encountered in the past. Only then are we prepared to decide.

Complimenting curiosity is another attitude engendered by the historian’s habit of thinking—empathy. This can be understood as looking out at the world through the eyes of the other person. I like this, from Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird: “You never really understand a person until you consider things from his point of view … Until you climb inside of his skin and walk around in it.” As I recall, other than in the history seminar I never explicitly encouraged students to try to be empathetic. But in an exit interview a colleague and I did with a history major he stated that’s what the history major did for him, which made me realize we had encouraged empathy without ever naming it as such.

In the year I spent as Dean for the Arts and Humanities I relied on my training as an historian almost every day on the job. I had to apply curiosity and empathy to make wise decisions. I had to read documents against each other, likewise with colleagues’ narratives. Being an historian doesn’t guarantee that you’ll get all those decisions right, but I don’t know how administrators without the training historians receive engage the problem-solving process well.

One final takeaway: I hope I’ve exploded the myth that there’s any tight linkage between major and career. Majors such as history that emphasize strong communications skills which follow on strong analytical skills which follow on strong research skills provide the best preparation for solving problems.

Majoring in history is not for the weak of heart. But neither is the world of work, or for that matter, life.

Marc Baer taught in Hope’s History department for 33 years, serving as chair for the last 6. He then served as the college’s interim Dean for Arts and Humanities for 13 months, retiring for good in June 2017.

Alumni Feature: Samantha L. Miller, Ph.D.

After Jeff Tyler’s History of Christianity class, the two courses I am most grateful for in all of my education are Janis Gibbs’s HIST 140 and Marc Baer’s HIST 400, the history major’s introductory and capstone classes, respectively. It was in these classes that I learned the art of research, which served as a foundation for all of the work to come. The classes in between the those two and all the varied experiences and opportunities I had as a history major together formed me as a historian.

I went on from Hope to get my M.Div. at Duke Divinity School and then my Ph.D. in historical theology from Marquette University. Now I teach church history and spiritual formation at Anderson University in Indiana. At every stage, I have been grateful for the formation I received as a Hope College history major.

The classes I took taught me how to research, to write, and to think. All of these skills were essential in graduate school, but the one that graduate school spent little time teaching was research. I was expected to know how to find sources and decide which were worth using. Professors assumed that I knew primary sources from secondary and the purpose of each. Assignments often had few instructions beyond, “15-20 pages, due on December 1.” I was expected to know how to take a paper from idea to final draft. Thanks to the work of Hope’s history faculty, I did.

Beyond research as the fundamental skill for papers—then a dissertation, and now conference presentations, articles, and books—the way Hope faculty taught me to research was empowering. They gave me steps to follow but trusted that I would do them and had high expectations. They taught me to do for myself and to try solving problems on my own. I was learning to think and work out the issues in my arguments; professors encouraged me to follow my curiosity. Now I use those same methods and stages of the intro and capstone classes (the annotated bibliographies, outlines, drafts, etc.) as I teach my own students to research in a History of Biblical Interpretation course.

In classes, I learned to speak up and have a voice because the history faculty knew how important discussion was for learning. I tested my ideas and learned to disagree respectfully with classmates. I learned that I was not always going to be the smartest person in the room; that formed humility as well as opened me to learn from classmates. In graduate school, I understood the value of listening to those with whom I disagreed, and now I require such discussions of my own students. (It’s also a skill and a posture much required in faculty meetings).

More than any class or any particular assignment or set of academic skills, however, I am grateful to my professors. They did the most work in preparing me to be a professor myself, and they did it by example. As they invited me into their offices and often their homes, as they worked alongside me on a research project, as they listened to my life and even prayed for me, I thought, “That’s the kind of professor I want to be.” And now as I sit across from students in my own office or as I make decisions about how to be fair in the classroom, I think about what Marc Baer or Janis Gibbs or Jeanine Petit would have done with me. I didn’t just come out of the Hope history department with a degree or with better research skills. I came out a well-rounded human being ready to serve.