“I’m interested in business and finance, so why should I major in history?” or, more bluntly, “Business is about buying and selling things, not writing term papers, so why should I study history?” I asked myself these same questions before I became a history major, and, today I am an in-house lawyer for a private equity and hedge fund firm.

Answering these questions requires looking at their two parts: first, understanding what it means to be a business person, and second, understanding what it means to study history at Hope–and then seeing the strong relationship between them. At its core, business is about human interaction: the art of buying and selling goods and services. Of course, numeracy is quite important. The art of business, however, is not merely about numbers on an Excel spreadsheet (no disrespect to Excel). Rather, it is about marshaling a team of people to achieve profit in buying from or selling to other people. Human relationships and communication about ideas, solutions (products and services) and the value proposition of those solutions are key. There are also whole ecosystems that support the sales organs of business: research and development, marketing, accounting, law, treasury, information technology, and human resources, just to name a few. History is a gateway to success in business because it focuses one’s thinking and communication and, most importantly, will teach you how to teach yourself new things so that new situations present opportunities and not obstacles. Let’s take a closer look at business and see the connections between it and the study of history.

First, a successful business career requires the ability to communicate clearly. Email is the common carrier of written business ideas, and communicating concepts like product value, pricing, quantity, delivery date, and charges, etc. demands clarity of communication. More than one million dollar deal has been fouled up because the salespeople were talking past each other and the email traffic was unclear as to what the parties really agreed to. Studying history at Hope College will demand discipline in thought and precision in communication. With your professors as your guides and classmates as co-venturers, you will learn to refine your ideas in presentations and writing and will learn to engage your colleagues’ ideas with care and candor. This is exactly the skill set you will need to employ to engage and persuade your colleagues and customers in business, each of whom will have their own ideas about strategy (in the case of colleagues) and value (in the case of customers).

Successful businesses also require leaders who are critical thinkers and can develop a sound strategy and express their ideas in the spoken word. Developing sound strategy requires clarity of thought while absorbing information from many sources–from colleagues, the media, the Intranet, trade publications and macroeconomic forces–to draw your own conclusions that may make or break your business. The study of history will give you a framework to sift the wheat from the chaff in the marketplace of ideas. You will learn which ideas have staying power and which do not. You will learn to persuade with your speaking in the classroom setting, and you will engage with the ideas of the past that have persuaded others (and perhaps you). Employing these skills with customers will give you an edge in today’s sales environment where selling a product requires persuading your customer of the value of your product, not just its price. You may be selling a product, a service, or your idea about how to solve a problem. Or, you may be evaluating someone else’s pitch to a solution. By studying history, you will also learn to see the mistakes and failures of others by reading about actions and words and their consequences–without having to make them yourself. Understanding your customers and your product’s value will permit you to see possible solutions and chart the right strategic course amid the challenges that will face you daily in business.

Lastly, a history degree will reward you with the confidence to make sound decisions for yourself, and the skepticism not to fall in love with your own ideas. The critical thinking skills of analysis will also permit you to teach yourself how to engage and learn new ideas, a crucial skill in today’s fast-paced, changing workforce.

history of World War I in Holland Michigan. Three students–Natalie Fulk, Avery Lowe, and Aine O’Connor–spent eight weeks digging into local archives and reading old newspapers, and put together a web exhibit that explores how this major global event transformed this small community on the shores of Lake Michigan. You can see it here:

history of World War I in Holland Michigan. Three students–Natalie Fulk, Avery Lowe, and Aine O’Connor–spent eight weeks digging into local archives and reading old newspapers, and put together a web exhibit that explores how this major global event transformed this small community on the shores of Lake Michigan. You can see it here:

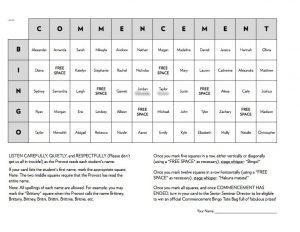

I have also added an element of winning prizes. Players who write their names on their cards and turn them in to me are entered into a drawing for a tote bag with swag inside. The bag is labeled “Commencement Bingo,” and my hope is that over the years it becomes a hot commodity.

I have also added an element of winning prizes. Players who write their names on their cards and turn them in to me are entered into a drawing for a tote bag with swag inside. The bag is labeled “Commencement Bingo,” and my hope is that over the years it becomes a hot commodity.

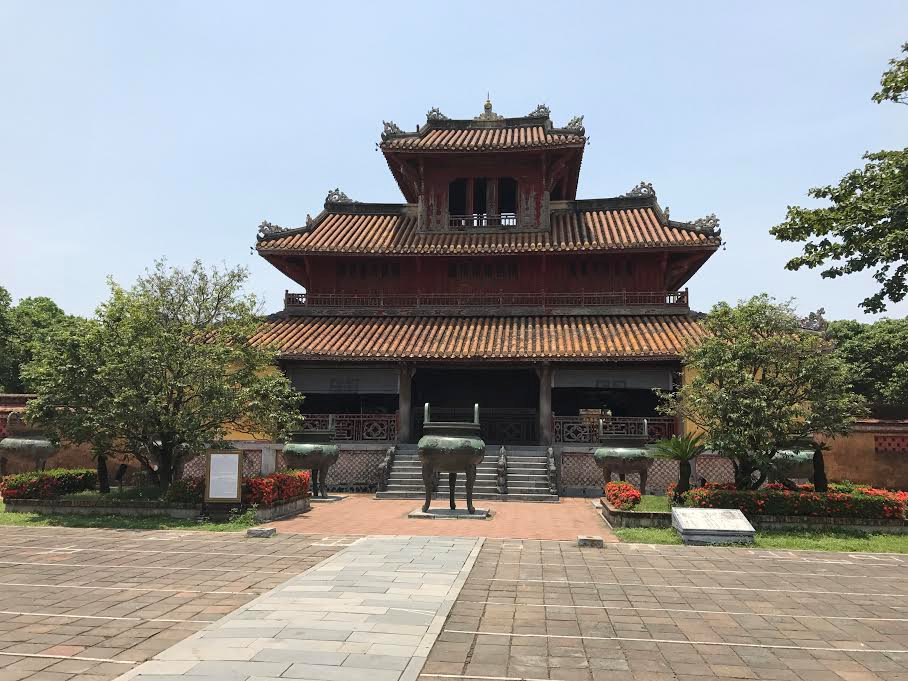

I’ve also had some really unique opportunities as a teacher. While spending a semester at the University of Aberdeen my junior year, I was bit hard by the travel bug and a few years after graduation I was hit with a desperate need to get out of the country. Unfortunately, the downside to teaching is that it’s not the most lucrative field and travel is expensive. Luckily I discovered a company that did tours for students and decided to give it a try. It’s fantastic! Traveling with students is amazing- getting to watch them experience firsthand what they learned in school is the ultimate teacher/history nerd high. I’ve done four tours with students- one to Greece and China and two to Italy (and I’m taking another group back to Italy this summer).

I’ve also had some really unique opportunities as a teacher. While spending a semester at the University of Aberdeen my junior year, I was bit hard by the travel bug and a few years after graduation I was hit with a desperate need to get out of the country. Unfortunately, the downside to teaching is that it’s not the most lucrative field and travel is expensive. Luckily I discovered a company that did tours for students and decided to give it a try. It’s fantastic! Traveling with students is amazing- getting to watch them experience firsthand what they learned in school is the ultimate teacher/history nerd high. I’ve done four tours with students- one to Greece and China and two to Italy (and I’m taking another group back to Italy this summer).

Seeing his work in person gave me a newfound appreciation of Ai as an artist. His versatility—mastery of both traditional art forms and digital media, as well as many genres in between—is even greater than what I previously read about him. Seeing the actual artworks, and not merely pictures of them, brought the man’s creative gifts to the fore. The visual arts “speak” eloquently where words fail.

Seeing his work in person gave me a newfound appreciation of Ai as an artist. His versatility—mastery of both traditional art forms and digital media, as well as many genres in between—is even greater than what I previously read about him. Seeing the actual artworks, and not merely pictures of them, brought the man’s creative gifts to the fore. The visual arts “speak” eloquently where words fail. One of my favorite installations at the exhibit was a pile of ceramic river crabs—each one skillfully crafted, inviting the viewer to a feast of sorts. River crabs are a treat in Chinese cuisine. Ai invited his fans in November 2010 to a party featuring river crabs upon learning that the authorities of Shanghai were going to demolish his newly built studio in a village near Shanghai. The destruction of the studio occurred in January 2011. The crabs, long digested by now, were an “eat-and-tell” commentary on the Chinese government’s motto of promoting social “harmony”—héxié—which sounds almost the same as river crabs—héxiè. The ceramic ones, of course, continue to “speak” in protest against the arbitrary powers of the Chinese state wherever they are exhibited.

One of my favorite installations at the exhibit was a pile of ceramic river crabs—each one skillfully crafted, inviting the viewer to a feast of sorts. River crabs are a treat in Chinese cuisine. Ai invited his fans in November 2010 to a party featuring river crabs upon learning that the authorities of Shanghai were going to demolish his newly built studio in a village near Shanghai. The destruction of the studio occurred in January 2011. The crabs, long digested by now, were an “eat-and-tell” commentary on the Chinese government’s motto of promoting social “harmony”—héxié—which sounds almost the same as river crabs—héxiè. The ceramic ones, of course, continue to “speak” in protest against the arbitrary powers of the Chinese state wherever they are exhibited.

you think your college prepared you to succeed in law school?” It seemed pretty clear the interviewer from my top choice law school did not believe Hope College prepared me for a competitive environment.

you think your college prepared you to succeed in law school?” It seemed pretty clear the interviewer from my top choice law school did not believe Hope College prepared me for a competitive environment.