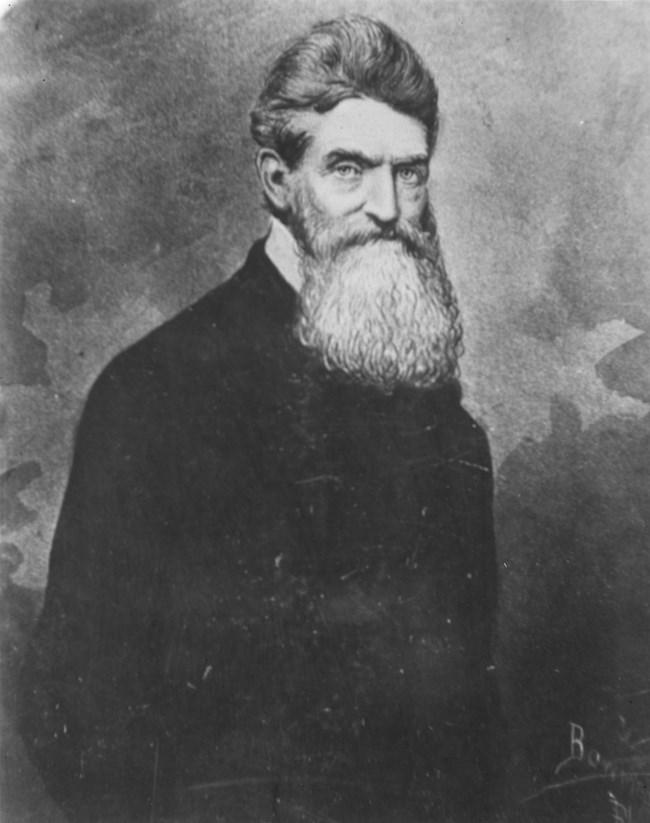

Hearing about the man who’d dedicated his life to eliminating the cancer of slavery from the United States was okay, but Hope College scholars Madison Coers, Kylie Sneller, and Katherine Dirkse wanted more. During their spring 2023 course Civil War America: Disruption & Destiny, winter weather forced the cancellation of a class trip to Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia. Madison, Kylie, and Kate had been excited to see where abolitionist John Brown had raided the federal arsenal on October 16, 1859, seeking to get free Blacks, Black slaves, and anti-slavery Whites to join him in a crusade to crush America’s brutal system of human bondage. Faced with not being able to make the trip, the scholars were disappointed but undaunted.

Madison, Kylie, and Kate moved forward, learning all they could about the life and legacy of John Brown who award-winning documentarian, Ken Burns, in his 1990 epic production “The Civil War,” described as “The Meteor” foreshadowing America’s prolonged, bloody civil conflict.

When the spring 2023 semester ended, the three scholars continued their examination to gain deeper insight into Brown’s attack on Harper’s Ferry which, along with enraging Southerners, caused a direct confrontation with the United States military.

Each new revelation convinced these determined researchers that the life and times of John Brown weren’t just history. They contained lessons and warnings for 21st-century Americans. Fortified by that motivation, Madison, Kylie, and Kate dissected the unraveling of Brown’s plan, starting from the moment he launched his attack, and continuing as circumstances steadily worsened for him and his raiders.

The townspeople of Harper’s Ferry proved more resilient and ferocious than Brown and his men had anticipated, and they put up a stiff resistance. Area Blacks, free and slave, stayed away, knowing that a mere raid would never be enough to eliminate the slavery which they knew to be not only oppressive but evil. Slavery had been making North America spectacularly wealthy since 1619 when a Dutch warship had delivered a cargo of twenty Africans to the English colony of Jamestown, Virginia.

After generations of being the target of slavery’s relentless violence, Blacks collectively understood that its beneficiaries would never relinquish that vile system without a fight of cataclysmic proportions. Still, a few African Americans like free Black, Dangerfield Newby, joined the raiders, and they were swiftly killed. The dead body of Newby, who’d participated in hopes of freeing his enslaved wife who was about to be sold, was mutilated and left out in the open on a Harper’s Ferry side street to rot for days.

The desire to know what had caused the United States, “conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal,” to, by 1859, be so economically dependent upon a system of human bondage reinforced for Madison, Kylie, and Kate the need to see Harper’s Ferry with their own eyes.

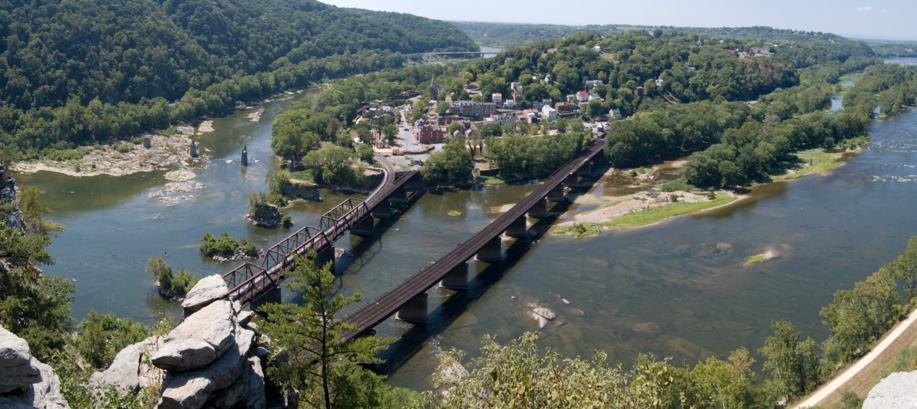

Professors get energized when encountering students who possess such impassioned intellectual curiosity like the kind displayed by Madison, Kylie, and Kate. Their enthusiasm was irresistible, so on Friday, August 11, 2023, we all set out for Harper’s Ferry, West Virginia. Early Saturday we took the short trip from our hotel in Maryland to Harper’s Ferry, crossing a bridge over the Potomac River.

(Shenandoah River on the left joins with Potomac River on the right and flows toward Washington, D.C.)

There, Madison, Kylie, and Kate saw the dangerous geography that had challenged both John Brown and his raiders in 1859, and the Union and Confederate forces who’d battled for the town during the Civil War (April 12, 1861 – April 9, 1865).

Surrounded by steep, craggy, mountains strewn with mammoth, forbidding boulders, we went from Maryland, into Virginia, and into West Virginia in less than five minutes. Once in Harper’s Ferry we drove to the Bolivar Heights battlefield, overlooking the town and walked the ground. Although not well-known like Antietam or Gettysburg, the Bolivar Heights battlefield was the scene of significant struggle during the Civil War, because Harper’s Ferry was a strategic location for both the North and the South.

Hundreds of tourists were visiting Harper’s Ferry that weekend, but they didn’t get to experience the historic site like Madison, Kylie, and Kate. On the banks of the Shenandoah River, the scholars stood mere inches from the flowing waters of that mighty river which had once turned the water wheels of cotton and grain mills on Virginius Island, adjacent to Harper’s Ferry.

Supports at Harper’s Ferry

They walked alongside the tracks of a railroad which, during the Civil War, had been a magnet for destruction by Confederate raiders like General Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson. They looked out across the Potomac at stone supports, the only remains of a Baltimore & Ohio railroad bridge that Jackson had destroyed so often that the B&O finally stopped attempting repairs.

Madison, Kylie, and Kate walked through the town’s Provost Marshal’s (military police) office and noticed the narrow doorways, lower room ceilings, and smaller furniture, gaining a good idea of the smaller stature of 19th-century Americans.

The three scholar-researchers were silent and reflective when they stepped into the firehouse, known as John Brown’s Fort, where he and his raiders made their last stand. Outnumbered and outgunned by a military detachment sent by train from Washington, D.C., Brown had run out of options. Detachment commanders Colonel Robert E. Lee and his subordinate, James Ewell Brown (Jeb) Stuart, then members of the United States Army, ordered Brown to surrender. He refused. The military detachment stormed the firehouse, ending the raid. Ten of Brown’s men had been killed, including two of his sons.

Standing in the location of the violent incident that sent John Brown, first, to prison in nearby Charlestown and, finally, to the hangman’s noose, Madison, Kylie, and Kate saw with their own eyes the landscape, historical explanations, and images of people who, in their own time, fought to make their nation a more just society. Their legacy joins with the struggle of people seeking to achieve justice for all in 21st-century America.

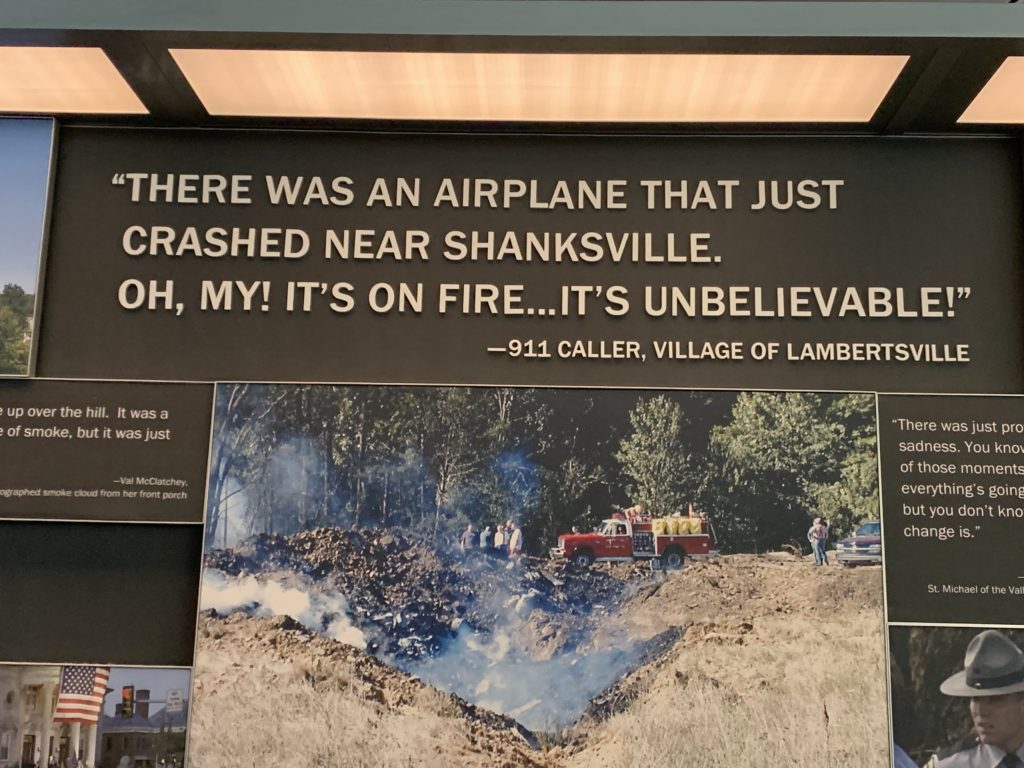

On Sunday, August 13, having explored as much of Harper’s Ferry as we could, we headed back to Michigan, making a detour to Shanksville, Pennsylvania, to honor heroes who gave their lives to save others on September 11, 2001.

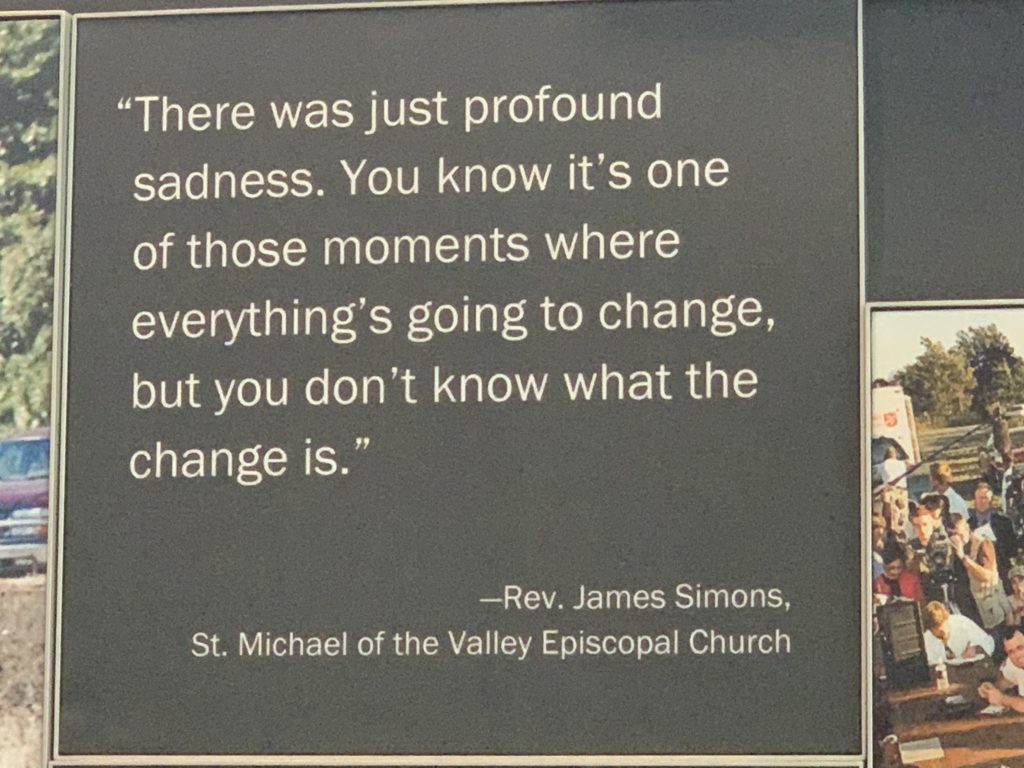

Madison, Kylie, and Kate were lost in deep reflection as they walked through the Flight 93 National Memorial, looking over exhibits of the unforgettable events of 9/11. They learned that the day had just started for the people of rural Shanksville when a hijacked commercial airliner, United 93, roared over their homes at treetop level. Windows shattered. Dishes vibrated off shelves. Car alarms blared. People dove for cover.

Passengers aboard United 93, learning that terrorists had used airliners to attack New York City’s World Trade Center and the Pentagon in Washington, D.C., deduced that the hijackers of their plane intended to also use it for attacking the nation’s capital.

While 9/11 happened before Madison, Kylie, and Kate were born, seeing the memorial with their own eyes helped them appreciate the shock of that day’s events. They were awestruck by the courage of passengers who’d fought back and seized control of their aircraft, refusing to let the terrorist cowards inflict more harm upon their country.

Moments before neutralizing the hijackers, one passenger, Todd Beamer, speaking with Chicago telephone operator Lisa Jefferson, asked her to recite the Lord’s Prayer with him. They prayed and then Lisa heard Todd say, “Are you guys ready?” They answered, and he said, “Let’s roll.”

When the passengers of United 93 took control of their airplane they’d been only twenty aerial minutes away from Washington, D. C. before crashing into the rolling hills of western Pennsylvania.

Madison, Kylie, and Kate have often heard me say that really knowing history requires going to where it happened and “walking the ground.” Be in the space where John Brown made his last stand. Hear the rushing Shenandoah River that once turned water wheels, making Virginius Island and Harper’s Ferry economic powerhouses. Stand on the side street where Dangerfield Newby’s body was left to rot. See the wounded earth, still healing from the crash of United 93.

Although separated by more than one hundred years from John Brown’s raid, Madison, Kylie, and Kate have no doubt that John Brown and his legacy remain relevant in 21st-century America. They know that the story of the passengers who prevented an atrocity on Nine-Eleven underscores the need for vigilance against national threats, foreign and domestic. They now know, understand, and feel history as scholars who’ve seen it with their own eyes.