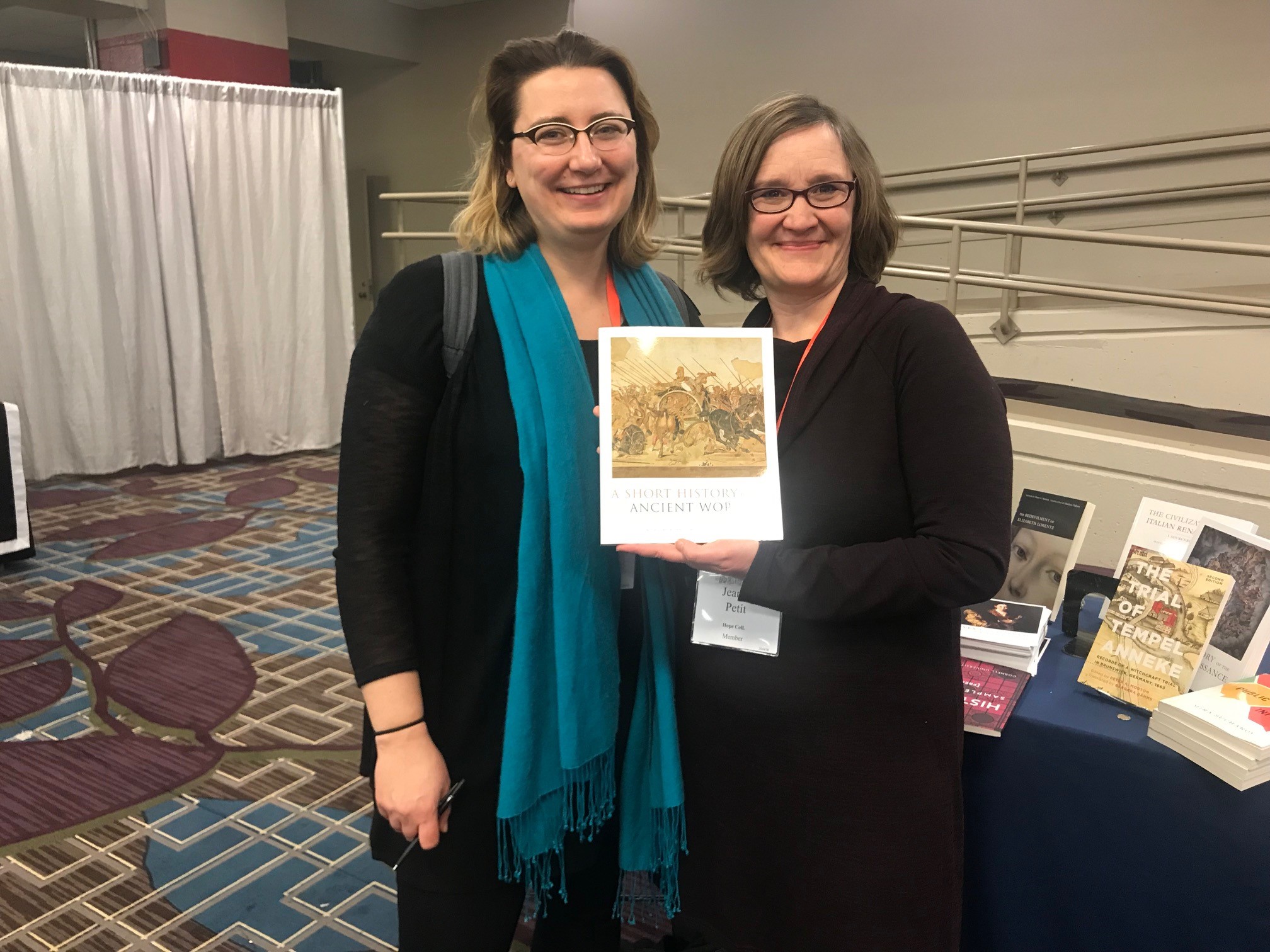

Not sure which History classes to take in the Spring? Our upper-level courses are available below for your perusing! If you have questions about them, please contact Dr. Jeanne Petit (petit@hope.edu).

History 141-01 A The Historian’s Vocation (2 Credits)

MWF 12:00 -12:50 PM | Janis Gibbs

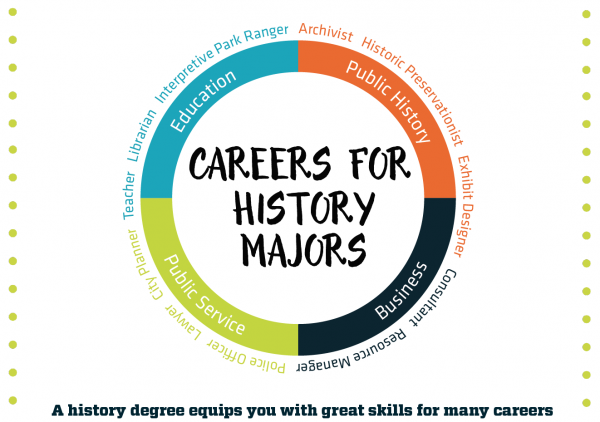

Do you love history, but struggle to answer when people ask you, “What are you going to do with that history major (or minor)?” In this course, we will examine the ways the study of history can become the foundation of your larger vocations in life, whether in a career or as a civically-engaged member of your community. We will consider how the skills you will develop as a historian (reading critically, researching widely, writing effectively) provide a foundation for a variety of careers, as well as for a life of meaning and purpose. As part of this course, students will work with the Boerigter Center for Calling and Career, learn practical skills, such as how to write a resume, and develop a plan for pursuing experiential learning opportunities that will aid in vocational exploration and discernment.

This course is required for all history majors and minors who entered Hope College in the Fall of 2018 and later.

Pre-requisite: HIST 140 (can be taken in the same semester)

History 200 01A: Ovid’s Metamorphoses (2 Credits)

R 6:30 – 9:20 PM |Albert Bell

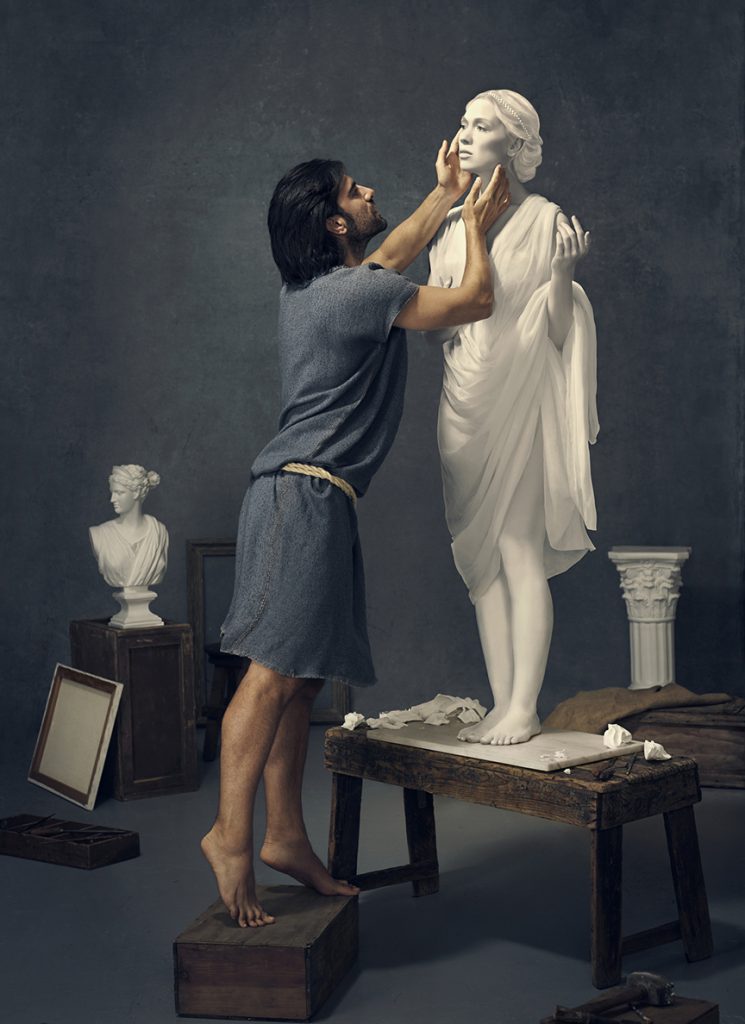

Ovid’s Metamorphoses are the source for many of the myths familiar to us from antiquity, such as Pyramis and Thisbe (the inspiration for Romeo and Juliet) and Pygmalion and Galatea (the inspiration for My Fair Lady). But Ovid ran into trouble. The emperor Augustus disliked the tone of his poetry so much he sent him into exile. This course will read selections from the poem and examine Ovid’s troubled life.

History 200 01B: Cosimo, The Renaissance Man (2 Credits)

R 6:30 – 9:20 PM | Albert Bell

Cosimo de Medici dominated the city of Florence for the first half of the 15th century without ever being elected or appointed to an office. Using wealth acquired from his bank, he hand-picked people who were chosen for office. He also hired artists to decorate the city and his home. But he lived in the terror of going to hell when he died because he was so rich and, according to Jesus, rich men could not get into heaven. Cosimo’s efforts to buy his way out of hell created the Italian Renaissance.

History 255 01: World War I America (GLD)

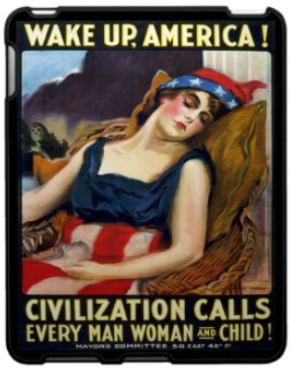

MWF 9:30 – 10:20 AM |Jeanne Petit

This course will examine how World War I changed the United States politically, socially, culturally, and economically. We will focus on the war’s impact in many areas, including industrialization, unionization, urbanization, the environmental movement, progressive politics, the freedom struggle of African Americans, women’s suffrage, immigration, the Red Scare, and the cultural transformations of “the Roaring Twenties.”

Flagged for domestic global learning.

History 268 01: Glory & Decadence: Russian History from Peter the Great to the USSR (GLI)

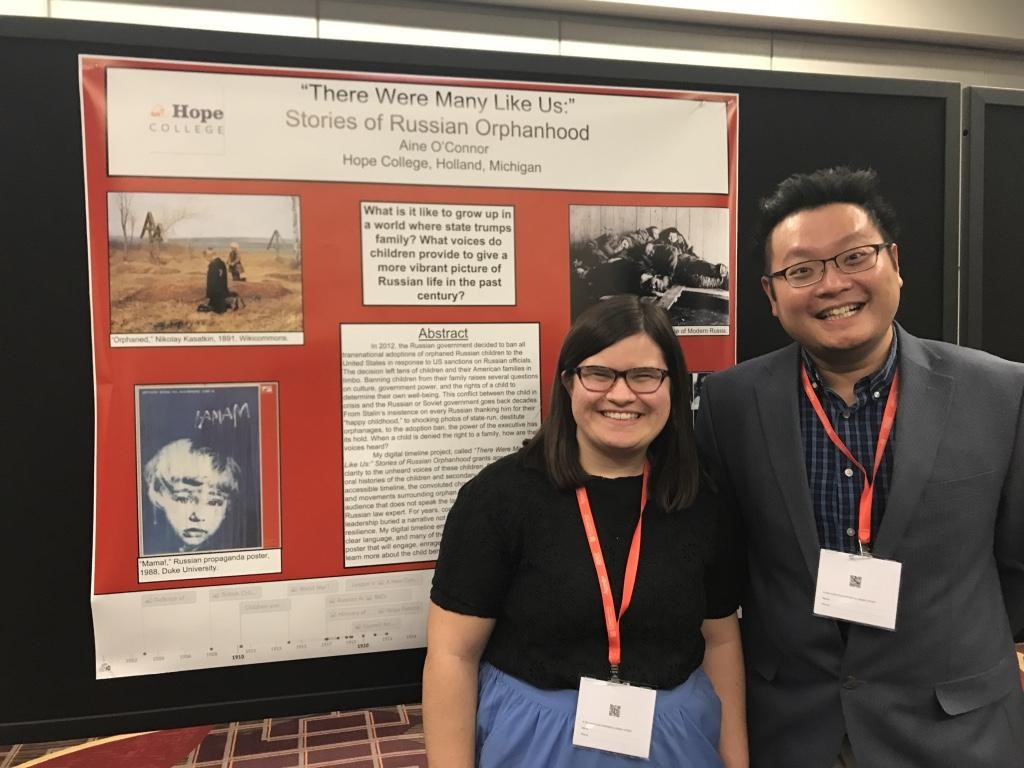

MW 1:00-1:50 PM |Wayne Tan

Russia is, arguably, one of the most influential nations today on the global stage. With humble beginnings as fragmented principalities, it grew into a vast empire spanning Asia and Europe by the 19th century and, as the core of the Soviet Union, dominated world politics for much of the 20th century. A land of untold riches, it was also a land of enigmas and contradictions. What is Russia’s identity today? What are the origins of Russian imperial traditions and institutions? How did its literature convey the political anxieties of the centuries? How did the 1917 Revolution affect the rest of the world? Why did the Soviet Union emerge and then slowly unravel? What lessons does the story of Russia hold for the future of global diplomacy and conflict resolution? This course explores these questions by surveying Russian history from the time of Peter the Great to the dissolution of the Soviet Union and recent developments in the 21st century.

This course is flagged for global learning international & fufills the regional requirement of the History major.

History 341 01: World War II: Collaboration and Resistance (GLI)

MWF 11:00-11:50 PM | Gloria Tseng

This course aims to explore one specific dimension of twentieth-century history, namely, how societies and individuals faced the moral ambiguities caused by the Second World War. Our goal is to learn about the significant events of the Second World War as it unfolded in different parts of the world. But more importantly, we will examine several noteworthy individuals and the specific circumstance in which they made significant moral choices and acted for good or for ill. It is the instructor’s hope that each person in the course will be challenged to consider what it means to act ethically in situations that require discernment and courage.

History 351 01: Slavery and Race in American (GLI)

MWF 3:00 – 4:20 PM | Fred Johnson

From its origins as a British colonial society to its dominance as a global superpower, the United States has struggled to resolve conflicts arising from issues of race, ethnicity, and immigration. This course examines how such factors have influenced the overall development of the United States while exploring strategies for reconciling those and related challenges confronting Americans in the 21st century.

History 370 01: Modern Middle East (GLI)

MWF 2:00-2:50 PM | Janis Gibbs

To understand what is going on in the Middle East today, it is crucial that we understand its history. In this course, we will survey the social, political, religious, geographic, and economic history of the Middle East, broadly defined to include the regions of North Africa and Iran, as well as the core lands of the Middle East, from Turkey through the eastern Mediterranean to the Arabian Peninsula and Egypt. Most of our attention will be devoted to the modern period—that is, the period between the 19th century and the present. To understand the context of the history of the modern Middle East, we’ll spend the first few weeks considering the rise of Islam and some of the facets of the history of the earlier Middle East that influence the region today.

Flagged for Global Learning.

Don’t forget! Dr. Lauren Janes is leading the 2020 Paris May Term: Art, History, & Global Citizenship.

This is a Grand Challenges Initiative Pathways course. This qualifies as HIST 131 (CHII), HIST295 (Europe Since 1500), Art 111 (FA1), or Senior Seminar. Contact Dr. Janes at janes@hope.edu to apply.

Hope Day of Giving starts this Thursday, April 11. This year it’s all about “Give to What you Love,” and for 36 hours you can give directly to support the Hope History Department as we work to teach historical thinking skills, expand students’ global engagement, and engage students in original research. You can help us keep making a difference by heading to

Hope Day of Giving starts this Thursday, April 11. This year it’s all about “Give to What you Love,” and for 36 hours you can give directly to support the Hope History Department as we work to teach historical thinking skills, expand students’ global engagement, and engage students in original research. You can help us keep making a difference by heading to

their communist party regimes during the Cold War. The course will explore how people were mobilized for and also spontaneously participated in the “national socialist revolution” of 1950s. We will also examine the changes in later decades as those in civil society contested their regimes in the 1960s and then shifted to conformity and retreat into private life in 1970s. Special emphasis will be placed on the compatibility between social justice and civil liberty.

their communist party regimes during the Cold War. The course will explore how people were mobilized for and also spontaneously participated in the “national socialist revolution” of 1950s. We will also examine the changes in later decades as those in civil society contested their regimes in the 1960s and then shifted to conformity and retreat into private life in 1970s. Special emphasis will be placed on the compatibility between social justice and civil liberty. everyday life? In this course, we will find answers to these questions through a survey of historical sources written since the 1800s about travels in foreign lands, the violent clash of empires, and the possibilities and limits of cultural exchanges. We will learn how to read texts and images—how English-speaking and non-English-speaking writers encountered the Other, how knowledge was disseminated across cultural borders, and how we, as contemporary readers, have inherited some of these assumptions. In other words, we use Asia as a space for questioning how we render the foreign vaguely familiar, and produce (and reproduce) what we thought we always knew.

everyday life? In this course, we will find answers to these questions through a survey of historical sources written since the 1800s about travels in foreign lands, the violent clash of empires, and the possibilities and limits of cultural exchanges. We will learn how to read texts and images—how English-speaking and non-English-speaking writers encountered the Other, how knowledge was disseminated across cultural borders, and how we, as contemporary readers, have inherited some of these assumptions. In other words, we use Asia as a space for questioning how we render the foreign vaguely familiar, and produce (and reproduce) what we thought we always knew. literature and architecture are still the basis for western culture. Sometimes they seem like modern people, except for those funny togas, but when we look at them more closely we see that their culture might have been a thin veneer over the barbarism of gladiator games, slavery, and vast inequality between social classes. Through the study of written documents and archaeological remains we will try to understand who the Romans were and why we are still so fascinated by them.

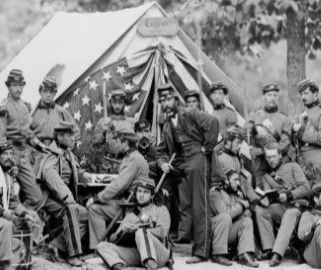

literature and architecture are still the basis for western culture. Sometimes they seem like modern people, except for those funny togas, but when we look at them more closely we see that their culture might have been a thin veneer over the barbarism of gladiator games, slavery, and vast inequality between social classes. Through the study of written documents and archaeological remains we will try to understand who the Romans were and why we are still so fascinated by them. Compromise and progressing through the Civil War and Reconstruction. During this period, as the United States expanded its territorial boundaries, forged a political identity, and further achieved a sense of national unity, sectional rivalries, industrialization, reform movements, and increasingly hostile confrontations over the language and interpretation of the Constitution led to crisis. This course will examine how those factors contributed toward the 1861-1865 Civil War, with subsequent special emphasis being placed upon how the conflict and post-war Reconstruction influenced America’s social, political, cultural, and economic development as it prepared to enter the 20th

Compromise and progressing through the Civil War and Reconstruction. During this period, as the United States expanded its territorial boundaries, forged a political identity, and further achieved a sense of national unity, sectional rivalries, industrialization, reform movements, and increasingly hostile confrontations over the language and interpretation of the Constitution led to crisis. This course will examine how those factors contributed toward the 1861-1865 Civil War, with subsequent special emphasis being placed upon how the conflict and post-war Reconstruction influenced America’s social, political, cultural, and economic development as it prepared to enter the 20th Roman ethnic perceptions that influenced the formation of Nazi ideology. We start by looking at Tacitus’ Germania, an ethnographic account of the peoples, geography, resources, and customs of the Germani, the Germanic tribes that eventually overthrew the Western Roman Empire. We will then analyze how this text, and the Roman perceptions of the Germanic peoples expressed in it, were appropriated by the leaders of the Third Reich to support their vision of racial superiority. This course will train students to recognize the dangers in using ancient documents to justify modern beliefs and practices.

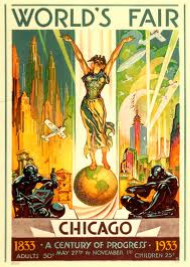

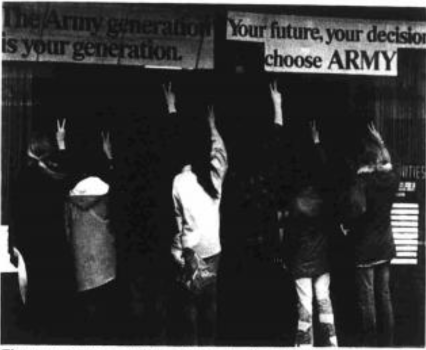

Roman ethnic perceptions that influenced the formation of Nazi ideology. We start by looking at Tacitus’ Germania, an ethnographic account of the peoples, geography, resources, and customs of the Germani, the Germanic tribes that eventually overthrew the Western Roman Empire. We will then analyze how this text, and the Roman perceptions of the Germanic peoples expressed in it, were appropriated by the leaders of the Third Reich to support their vision of racial superiority. This course will train students to recognize the dangers in using ancient documents to justify modern beliefs and practices. examines the ways both ordinary people and elites created, challenged and shaped American culture. Students will consider cultural history on two levels. First, we will explore changes in the ways American men and women of different classes, races, and regions expressed themselves through popular and high culture—including forms like vaudeville, world’s fairs, movies, and literary movements like the Harlem Renaissance. Second, we will analyze the influence of cultural ideas on political, economic and social changes, such as fights for African-American and women’s rights, the emergence of consumer culture, class struggles during the Great Depression, participation in World War II, protesting in the 1960s, and the rise of conservatism in the 1980s. Students will learn the various ways historians interpret cultural phenomena and then do their own interpretations in an extensive research paper. Flagged for global learning domestic.

examines the ways both ordinary people and elites created, challenged and shaped American culture. Students will consider cultural history on two levels. First, we will explore changes in the ways American men and women of different classes, races, and regions expressed themselves through popular and high culture—including forms like vaudeville, world’s fairs, movies, and literary movements like the Harlem Renaissance. Second, we will analyze the influence of cultural ideas on political, economic and social changes, such as fights for African-American and women’s rights, the emergence of consumer culture, class struggles during the Great Depression, participation in World War II, protesting in the 1960s, and the rise of conservatism in the 1980s. Students will learn the various ways historians interpret cultural phenomena and then do their own interpretations in an extensive research paper. Flagged for global learning domestic. in a multifaceted relationship that began in the eighteenth century. The US was a young nation; China was a declining empire. Yankee merchants were eager to make a fortune in the China trade, and missionaries were eager to take the Gospel to “China’s millions.” As the young nation became the leader of the free world, and revolutionaries turned China into a Communist state, the two countries have been both allies and enemies, and their citizens have regarded “the other” with curiosity, benevolence, suspicion, admiration, contempt, or hostility at different points in the two countries’ relationship. This course offers a historical overview of this evolving relationship.

in a multifaceted relationship that began in the eighteenth century. The US was a young nation; China was a declining empire. Yankee merchants were eager to make a fortune in the China trade, and missionaries were eager to take the Gospel to “China’s millions.” As the young nation became the leader of the free world, and revolutionaries turned China into a Communist state, the two countries have been both allies and enemies, and their citizens have regarded “the other” with curiosity, benevolence, suspicion, admiration, contempt, or hostility at different points in the two countries’ relationship. This course offers a historical overview of this evolving relationship.

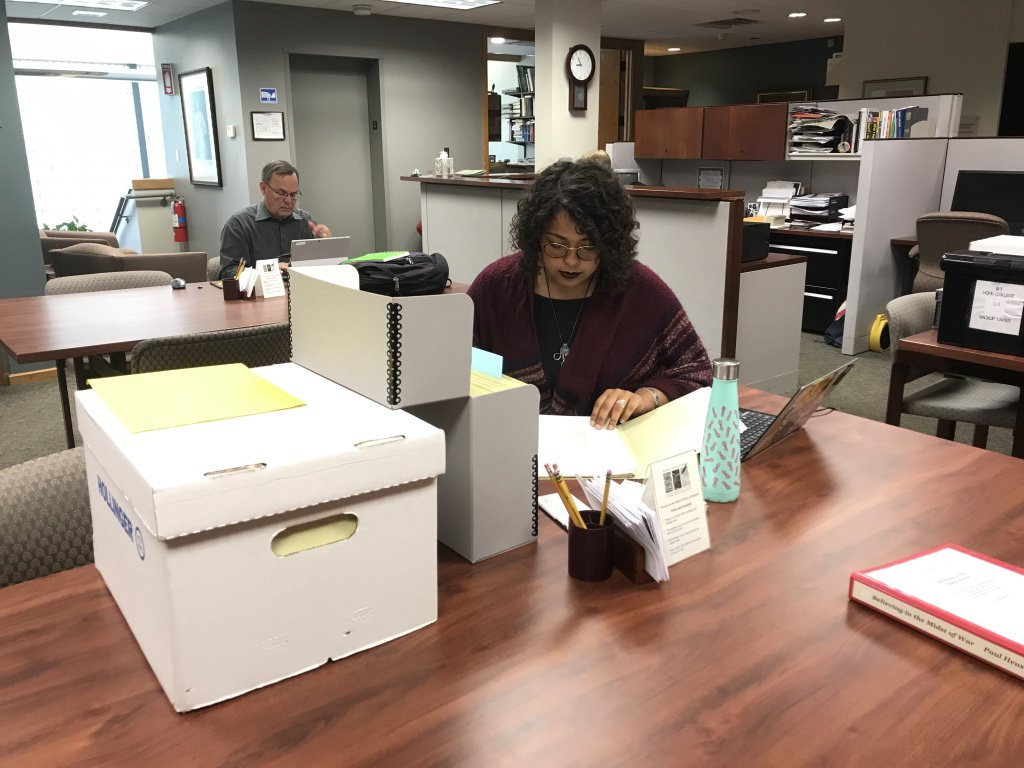

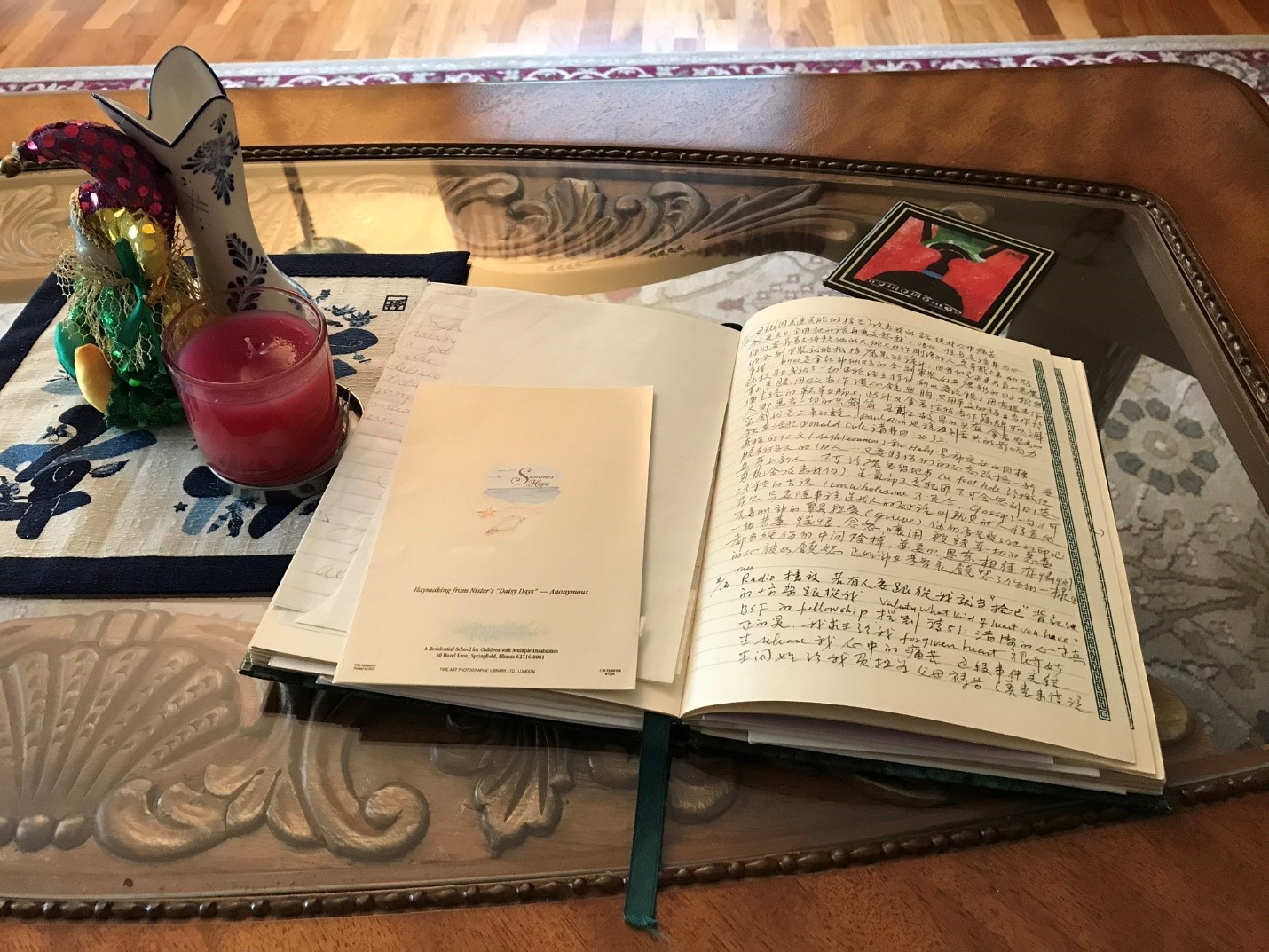

The Historian’s Craft

The Historian’s Craft As students of history invariably find out by experience, research proposals often need to be modified in the course of a project. I had several surprises once we started going through the first notebook. First, I had envisioned neat, print-like handwriting that I could skim quickly to get the gist of each journal entry. The reality was far different, and especially challenging for a non-alphabetical language such as Chinese. Second, I had approached it as a project, but it was much more personal for my cousin. I wanted to be systematic; my cousin wanted to have an entire entry translated when we came upon an entry that mentioned him or his two sisters. My “research proposal” had to be modified: we made bullet points of most entries and translated the entries for which my cousin wanted translations. In the end, we got through only one notebook. Third, I had to give up my perfectionism; finding the best expression in English for a certain Chinese term really didn’t matter as long as I got the meaning across. Fourth, and the greatest surprise, was the various effects the translation of the first notebook had on the family. A flurry of emails ensued after my cousin sent off the translation to his sisters and father. My uncle, who had wanted to throw away the journals, thanked me for my labors. Each person in the family remembered different details in the journal entries, and the same material evoked varied reactions. Should I have been surprised? Haven’t I always known that history is about people, who always have different perspectives, emotions, and responses to circumstances and events? I was humbled by the reminder that when we write history, we’re dealing with people and telling their stories. We owe it to our subjects to be truthful, not only to events and sources, but also to their perspectives. It was an “Annales” moment for me.

As students of history invariably find out by experience, research proposals often need to be modified in the course of a project. I had several surprises once we started going through the first notebook. First, I had envisioned neat, print-like handwriting that I could skim quickly to get the gist of each journal entry. The reality was far different, and especially challenging for a non-alphabetical language such as Chinese. Second, I had approached it as a project, but it was much more personal for my cousin. I wanted to be systematic; my cousin wanted to have an entire entry translated when we came upon an entry that mentioned him or his two sisters. My “research proposal” had to be modified: we made bullet points of most entries and translated the entries for which my cousin wanted translations. In the end, we got through only one notebook. Third, I had to give up my perfectionism; finding the best expression in English for a certain Chinese term really didn’t matter as long as I got the meaning across. Fourth, and the greatest surprise, was the various effects the translation of the first notebook had on the family. A flurry of emails ensued after my cousin sent off the translation to his sisters and father. My uncle, who had wanted to throw away the journals, thanked me for my labors. Each person in the family remembered different details in the journal entries, and the same material evoked varied reactions. Should I have been surprised? Haven’t I always known that history is about people, who always have different perspectives, emotions, and responses to circumstances and events? I was humbled by the reminder that when we write history, we’re dealing with people and telling their stories. We owe it to our subjects to be truthful, not only to events and sources, but also to their perspectives. It was an “Annales” moment for me.