By Jeanne Petit

One hundred years ago, on April 2, 1917, President Woodrow Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany, and on April 4, Congress declared war against Germany. As we reflect on the impact of this war on our nation, we first turn to the loss of over 100,000 American soldiers in combat or from disease. In the larger picture, however, the United States losses pale in comparison to the millions of Europeans who perished. The American Expeditionary Force only participated in a major way during the last seven months, although their contribution was decisive in many battles. Yet when we look beyond the U.S. military role, we can see the many ways that World War I impacted American society.

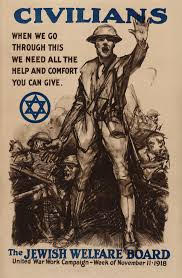

For one, the war forced Americans to face how diverse their society had become. Since the Civil War, over 20 million immigrants had come to the United States, making up 15% of the population. Native-born troops found themselves fighting alongside immigrants from 46 nations. Officials also had to confront the greater religious diversity as they built the army. At first, the War Department asked the Protestant Young Men’s Christian Association to provide recreation services to the troops, but they received complaints from Catholics and Jews, who argued that large percentages of the soldiers, particularly the nearly 20% who were immigrants, were not Protestant. To accommodate this religious diversity, the military allowed the Knights of Columbus, and the Jewish Welfare Board to also have recreational facilities.

For one, the war forced Americans to face how diverse their society had become. Since the Civil War, over 20 million immigrants had come to the United States, making up 15% of the population. Native-born troops found themselves fighting alongside immigrants from 46 nations. Officials also had to confront the greater religious diversity as they built the army. At first, the War Department asked the Protestant Young Men’s Christian Association to provide recreation services to the troops, but they received complaints from Catholics and Jews, who argued that large percentages of the soldiers, particularly the nearly 20% who were immigrants, were not Protestant. To accommodate this religious diversity, the military allowed the Knights of Columbus, and the Jewish Welfare Board to also have recreational facilities.

The War Department did a less impressive job of dealing with African-American soldiers. The Army was still segregated, and African Americans faced continual abuse and violence and were relegated to the worst jobs, like digging latrines and removing the dead. Those who had the opportunity to engage in battle proved their worth as soldiers, such as the infantry regiment known as the Harlem Hellfighters. They fought for 190 days and ceded no ground to the Germans. They received the French Croix de Guerre and returned as heroes.

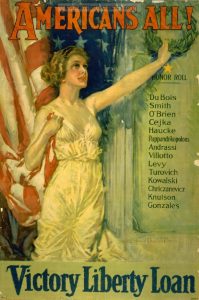

The nation’s growing diversity also became an issue at home. Some leaders, like Theodore Roosevelt, argued that immigrants had to reject “the hyphen” and prove themselves to be “100% American.” German Americans felt the brunt of suspicion as native-born Americans went to far as to purge German words from their vocabularies. For instance, sauerkraut became known as “freedom cabbage.” Yet the Wilson administration knew that they could not alienate immigrants, and they used propaganda to promote their inclusion into American civic life. One poster, titled “Americans All.” had an image of Lady Liberty and an “honor roll” of Irish, Italian, Slavic, Scandinavian and other ethnic names (although not German). Many immigrants embraced the opportunity to prove their love of the nation by enlisting in the Army, participating in Liberty Loan campaigns, and volunteering for the Red Cross.

The nation’s growing diversity also became an issue at home. Some leaders, like Theodore Roosevelt, argued that immigrants had to reject “the hyphen” and prove themselves to be “100% American.” German Americans felt the brunt of suspicion as native-born Americans went to far as to purge German words from their vocabularies. For instance, sauerkraut became known as “freedom cabbage.” Yet the Wilson administration knew that they could not alienate immigrants, and they used propaganda to promote their inclusion into American civic life. One poster, titled “Americans All.” had an image of Lady Liberty and an “honor roll” of Irish, Italian, Slavic, Scandinavian and other ethnic names (although not German). Many immigrants embraced the opportunity to prove their love of the nation by enlisting in the Army, participating in Liberty Loan campaigns, and volunteering for the Red Cross.

World War I also made apparent to Americans how central women had become to their society. Over 20,000 women served as nurses during the war, and for the first time, active duty women served in other capacities, mostly clerical duties that freed men to fight. Thousands of women also went to France and worked for the YMCA and Red Cross. The women known as “Hello Girls” served as bilingual telephone operators and the Salvation Army’s “doughnut girls,” named after the treat they made for soldiers, became the most popular sight on the front. Beyond service to the military, American women on the home front took up industrial jobs in munitions factories and other areas as men volunteered or were drafted.

During this time, the decades-long fight for women’s suffrage reached a crescendo. Some women took militant action, such as when Alice Paul chained herself to the White House gates and compared Wilson’s anti-suffrage stance to the oppression of the German Kaiser. Other activists, like Elizabeth Cady Stanton, argued that wartime service proved that women deserved full civil rights. Woodrow Wilson became convinced, and on September 30, 1918, he backed women’s suffrage, declaring, “we have made partners of the women in this war…Shall we admit them only to a partnership of suffering and sacrifice and toil and not to a partnership of privilege and right?” Congress passed the 19th Amendment a year later, and on August 18, 1920, it was finally ratified.

During this time, the decades-long fight for women’s suffrage reached a crescendo. Some women took militant action, such as when Alice Paul chained herself to the White House gates and compared Wilson’s anti-suffrage stance to the oppression of the German Kaiser. Other activists, like Elizabeth Cady Stanton, argued that wartime service proved that women deserved full civil rights. Woodrow Wilson became convinced, and on September 30, 1918, he backed women’s suffrage, declaring, “we have made partners of the women in this war…Shall we admit them only to a partnership of suffering and sacrifice and toil and not to a partnership of privilege and right?” Congress passed the 19th Amendment a year later, and on August 18, 1920, it was finally ratified.

This summer, I will be working with a team of history majors to examine the impact of World War I on a very specific part of the U.S. home front: Holland, Michigan. We will do research in local and regional archives to find the perspectives of the soldiers who went to France to fight the Germans and Siberia to fight the Red Army. We will also read about the perspectives of the men and women who stayed in Holland and see how the war shaped their lives. One central question we will explore is: how did the war affect the ways the people in this community, largely made up of Dutch immigrants and their descendants, saw themselves as Americans? We will be creating a web exhibit that will present our findings–look for it in the fall of 2017!

Last summer, when I heard about the grand reopening of the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Museum and the new Devos Learning Center, I knew I had to learn more. I made a visit to the museum, and while there, I had the opportunity to meet with the museum’s education specialist, Barbara McGregor. I expressed interest in volunteering at the museum throughout the summer, but Barbara had a better idea. She was in need of support to prepare for the launch of the new learning center and offered me a special internship. As a student pursuing a degree in secondary education with a focus on history and political science, it was an incredible offer, and I asked how quickly I could start.

Last summer, when I heard about the grand reopening of the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Museum and the new Devos Learning Center, I knew I had to learn more. I made a visit to the museum, and while there, I had the opportunity to meet with the museum’s education specialist, Barbara McGregor. I expressed interest in volunteering at the museum throughout the summer, but Barbara had a better idea. She was in need of support to prepare for the launch of the new learning center and offered me a special internship. As a student pursuing a degree in secondary education with a focus on history and political science, it was an incredible offer, and I asked how quickly I could start.

Fulbright Scholarships are part of a program funded by the U.S. State Department. The program has many elements, but the one that matters to Hope students is the U.S. Student Program, which sends recent graduates abroad for a year, to teach English, or to conduct research or a program of study in their academic areas of interest. The program is national and competitive, but Hope students have a history of doing well in the competition. Most students start in the spring of their junior year, choosing their potential host country and figuring out whether they want to teach, research, or study. Seniors sometimes start the program in the spring, but need to wait a year after graduation before their grants are awarded. We also work with Hope alumni who want to apply after having been out of college for a few years.

Fulbright Scholarships are part of a program funded by the U.S. State Department. The program has many elements, but the one that matters to Hope students is the U.S. Student Program, which sends recent graduates abroad for a year, to teach English, or to conduct research or a program of study in their academic areas of interest. The program is national and competitive, but Hope students have a history of doing well in the competition. Most students start in the spring of their junior year, choosing their potential host country and figuring out whether they want to teach, research, or study. Seniors sometimes start the program in the spring, but need to wait a year after graduation before their grants are awarded. We also work with Hope alumni who want to apply after having been out of college for a few years.

I arrived in D.C. a couple of weeks ago as part of Hope’s Washington Honors Semester, excited to tackle the new challenges of living in a city. For those who don’t know me, or have not heard my ramble on about my interests, I am a History and Political Science double major with a focus in African American studies and public history. Museums have always been a passion of mine and I will find any excuse to spend all of my free time in them. Currently, I am an intern in the Office of Programs and Strategic Initiatives and the African Americans Studies program at the National Museum of American History. Much of my time has been spent exploring the museum and the city and I have loved the experience.

I arrived in D.C. a couple of weeks ago as part of Hope’s Washington Honors Semester, excited to tackle the new challenges of living in a city. For those who don’t know me, or have not heard my ramble on about my interests, I am a History and Political Science double major with a focus in African American studies and public history. Museums have always been a passion of mine and I will find any excuse to spend all of my free time in them. Currently, I am an intern in the Office of Programs and Strategic Initiatives and the African Americans Studies program at the National Museum of American History. Much of my time has been spent exploring the museum and the city and I have loved the experience.

easure of attending sessions about fashion history, Catholic thinkers of the 20th Century, and using history to write about current events. I also participated in a session about religious encounters during World War II and presented a paper titled “Demand for National Action: Protestant and Catholic Women in World War I America.” Someone even tweeted our session! You can read his tweets here:

easure of attending sessions about fashion history, Catholic thinkers of the 20th Century, and using history to write about current events. I also participated in a session about religious encounters during World War II and presented a paper titled “Demand for National Action: Protestant and Catholic Women in World War I America.” Someone even tweeted our session! You can read his tweets here: