At a time when the humanities appear to be in a crisis mode, with declining enrollment numbers across campuses, I want to share my thoughts about how, from a faculty’s perspective, the work I do in history relates back to the core issue of what it means to be in touch with my humanistic outlook. As a historian, it is my job to think critically, articulate my thoughts clearly, and write cogently. This was what I was taught in school and also a lesson that is dear to my heart. Herein lies a question that I had only recently started to reflect on: Can the process of doing history be one that is also rooted in emotions? That is to say, a process that doesn’t pit mind against heart, but instead, one that marries mind with heart? For the longest time, haunting every analytical turn of mind is the fear (stoked gently by conventional wisdom) that emotions cloud judgment. Analysis at its best, we are told, should be clinical, exacting, and stripped of emotional biases in order to present an objective truth. But does it have to be this way—for a historian, fully absorbed as is to be expected in his/her task, to maintain an emotional distance from the object of analysis? After all, is not analysis itself also a subjective experience that is intended to produce a personal interpretive result?

Perhaps owing to my research background in disability history, I am partial to methodological approaches that scour the pages of history to seek out traces of unrepresented and underrepresented communities in our societies. The point of my work, summarized here at the risk of sounding hackneyed, is to give a voice to these communities—communities that have historically struggled for the right to exist despite as well as because of their disabilities and for the opportunities for a better quality of life. This research has also led me down a different yet parallel path of personal growth: I feel deeply for the human subjects who are at the center of the narratives I construct. To disclaim the power of emotions would be disingenuous. I could not ignore the anguished pain I felt upon first reading the case of Carrie Buck (institutionalized and sterilized against her will) in early 20th-century America and her uphill fight against a social system bent on condemning any sign of feeble-mindedness. She was forever ensconced in a legacy of martyrdom because of the inhumanity she had suffered. Nor can I suppress the upwelling current (and sometimes sinking weight) of grief and distress each time I bury myself in victims’ harrowing stories about radiation sickness in the wake of the 1945 atomic bombings of Japan and more recent local and state media reports of residents’ concerns about PFAS contamination and lead exposures from the alleged industrial pollution of drinking water. If these feelings fall under the broad lexical reach of the word “empathy”, then I am proud to identify with an empathetic audience.

There is a reason why I turn to writing. If I could reinvent the metaphor of giving a voice to the voiceless, I see a new significance in restoring emotions to my stories and perspectives—not the formulaic types that evoke sympathy as the be-all and end-all of writing, but the kinds that provide a well-considered context that would frame the writer’s emotional response. The stories I write shape the narratives I tell inside and outside the classroom, in the repertoire of courses I teach here at Hope College and also the everyday conversations I have. Words themselves are a historian’s consummate instruments to disclose thoughtfully an emotional inner self that is inseparable from the context. The singular act of writing, in all its complexity, weaves together the dense substance of words, which impart an emotional complexion to prose. To say this differently, words reveal as much about the emotional state of the writer as they do about the emotional profiles of the characters portrayed and described. That is why when I write, I own my words and take ownership of my emotions. When I speak, I do likewise. This is the emotional responsibility of a historian to himself/herself and to the subjects at hand and my personal response to why history and, more broadly, humanities matter to us. Now more than before.

So I’m in a social setting, mingling with a new acquaintance. I’m asked what I do.

So I’m in a social setting, mingling with a new acquaintance. I’m asked what I do. Chad Carlson is Associate Professor of Kinesiology and Assistant Men’s Basketball Coach at Hope College. He will be leading a History Colloquium titled “Why March Madness Matters: Reflections on a Popular Sporting Event’s Forgotten History. The talk will take place on

Chad Carlson is Associate Professor of Kinesiology and Assistant Men’s Basketball Coach at Hope College. He will be leading a History Colloquium titled “Why March Madness Matters: Reflections on a Popular Sporting Event’s Forgotten History. The talk will take place on

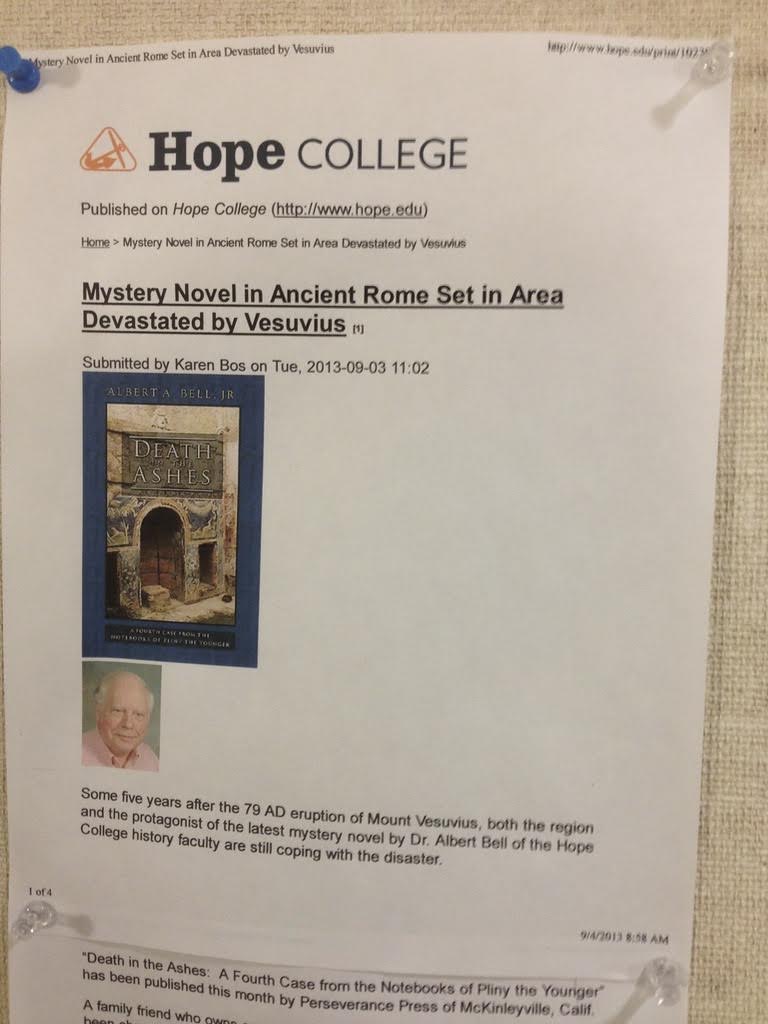

I’ve been gratified by critical comments about the books. Library Journal said the second in the series, The Blood of Caesar, was one of the 5 Best Mysteries of 2008, “a masterpiece of the historical mystery genre.” One reviewer of the sixth book, Fortune’s Fool, said, “Bell reinforces his place among those who are pushing the mystery beyond genre, toward the literary.” I thought I was just telling stories.

I’ve been gratified by critical comments about the books. Library Journal said the second in the series, The Blood of Caesar, was one of the 5 Best Mysteries of 2008, “a masterpiece of the historical mystery genre.” One reviewer of the sixth book, Fortune’s Fool, said, “Bell reinforces his place among those who are pushing the mystery beyond genre, toward the literary.” I thought I was just telling stories.

Happy New Year, and welcome back to Hope students, faculty, and staff!

Happy New Year, and welcome back to Hope students, faculty, and staff!

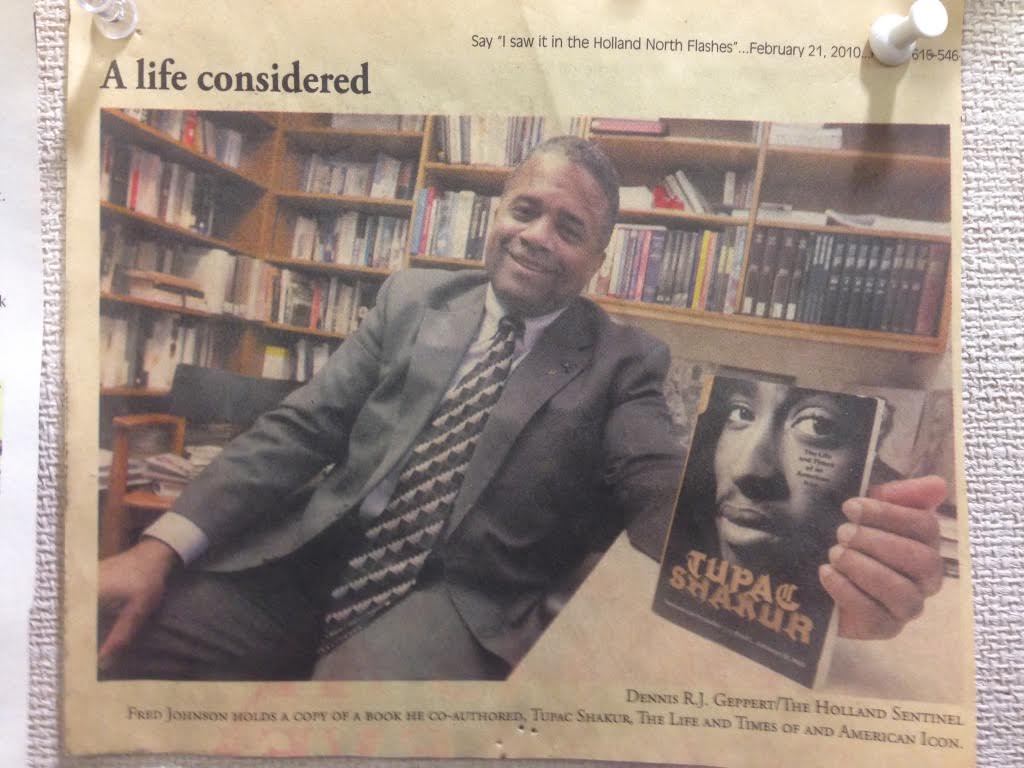

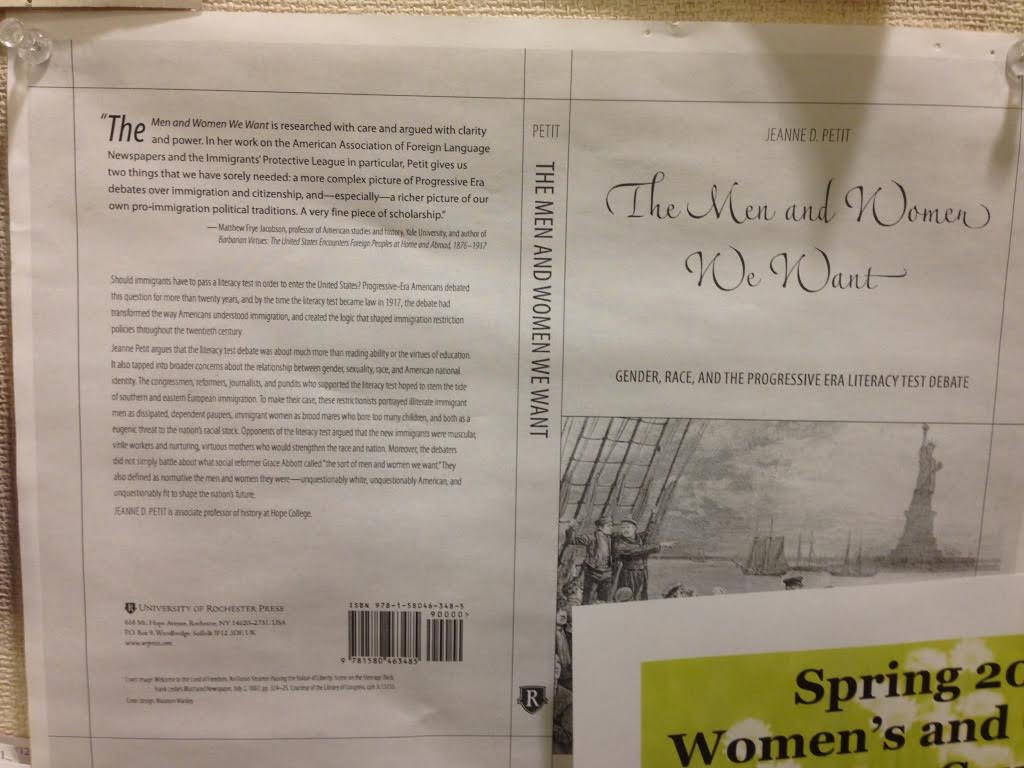

And finally, the printout of the cover of my book,

And finally, the printout of the cover of my book,