sabbatical (n): a break from customary work to acquire new skills or knowledge, traditionally occurring every seventh year

Breaks Away: Sabbatical Stories of Hope

Each academic year, a number of Hope faculty take sabbatical leaves away from the college, submersing themselves for extended periods of time into their favored fields of inquiry. If viewed from above and all together, those fields would look like a calico landscape, so varied and colorful is the topography of their collective research, writing, and creative pursuits. Offering both restoration and adventure, sabbaticals are a bit like information and imagination transfusions. These breaks away from normal classroom and committee work give Hope academicians a boost to reinforce and revitalize their teaching and scholarship.

The U.S. folk singer/songwriter movement of the 1960s and 1970s gave us Arlo Guthrie, Bob Dylan and Judy Collins. A decade or two later, Latin Americans saw the rise of their own folk heroes Mercedes Sosa, Victor Jara, Maria Elena Walsh and Ruben Blades.

Each singer/songwriter/activist — a half a world away from each other — was using music to accomplish the same goals for their countries: to artistically and poignantly express the current social realities of injustice in order to move nations of people to protest but ultimately, to love.

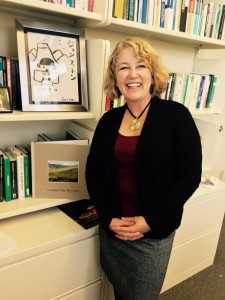

The New Song Movement, born out of struggle, political repression and sometimes civil wars in Central and South America, was the break-away focus of Professor Sylvia Kallemeyn, associate professor of Spanish, during her sabbatical leave from Hope in 2014-15. Kallemeyn’s goal was to make these songs more accessible to students in her Spanish language classes through the study of the folk-inspired and socially-committed music of this era, first in Ecuador and then in the States.

“I want my students to listen to these enduring songs in Spanish, hear the message and get to know these singers’ cause and the history of why they wrote and sang what they wrote and sang. By using culturally authentic words and rhythms students learn these musical revolutionaries’ lessons in context. At the same time, the songs increase students’ vocabularies and help illuminate Spanish grammatical concepts.”

One good example of such a song was written by Ruben Blades, called the “poet of the people.” A native of Panama, Blades wrote a ballad to memorialize Father Antonio Romero, an archbishop who had been assassinated while conducting a Catholic mass in El Salvador. Romero had been critical of the right-wing government’s atrocities in the civil war there, and he publicly championed the rights of the poor. In “Suenan las campanas otra vez” (“The bells toll again”), Blades sang of the archbishop’s sacrifice, a harbinger to Pope Francis’ recent actions to declare Romero a martyr, almost 35 years later.

Here a few lines from Blades’ song:

Suenan las campanas uno, dos tres (The bells toll one, two three)

Por el Padre Antonio y su monaguillo Andrés… (For Father Antonio and his altar boy Andrés)

El Padre condena la violencia (The Father condemns the violence)

Sabe por experiencia que no es la solución. (He knows from experience that it is not the answer.)

Les habla de amor y de justicia… (He speaks of love and of justice…)

Antonio cayó, hostia en mano y sin saber por qué (Antonio fell, the host in hand, and not knowing why)

Andrés se murió a su lado sin conocer a Pelé… (Andrés died at his side without meeting Pelé…)

Vamos, que nos llaman (Let’s go, they’re calling us)

Para celebrar (to celebrate)

Nuestra Identidad (our identity)

Porque un pueblo unido (Because a united people)

No, no, jamás será vencido… (Will never, ever be defeated…)

Suena las campanas (The bells toll)

El mundo va a cambiar. (The world is going to change.)

Blades ends with his musical message with hope. It echoes across time and cultural boundaries.

In class, “this song can be approached in a variety of ways,” explains Kallemeyn. “The cultural and historical setting can be explored through student research and discussion as well as the background and life of Archbishop Romero and Ruben Blades… Vocabulary related to themes of love and justice, as well as religious terms, run throughout the song. Verb tenses vary as well,” making the song a well-rounded lesson on Latin American culture, history and language.

“Learning goes deeper when you are out of your own world and in another.”

This method of teaching language through lyrical and musical messaging has been a hit and an inspiration for Kallemeyn. After all, what college student would not want to listen to somewhat contemporary music in class?

“I discovered poets I was not acquainted with and found new singer/songwriters from all over Latin America, too. I have a better understanding of, and appreciation for, the New Song Movement and the cantautores who tell their unofficial story of struggle… Learning goes deeper when you are out of your own world and in another. And that is a benefit of a sabbatical, not just for me but for my students, too.”

—

Sylvia Kallemeyn is an associate professor of Spanish in the Department of Modern and Classical Languages at Hope College.