sabbatical (n): a break from customary work to acquire new skills or knowledge, traditionally occurring every seventh year

Breaks Away: Sabbatical Stories of Hope

Each academic year, a number of Hope faculty take sabbatical leaves away from the college, submersing themselves for extended periods of time into their favored fields of inquiry. If viewed from above and all together, those fields would look like a calico landscape, so varied and colorful is the topography of their collective research, writing, and creative pursuits. Offering restoration and adventure both, sabbaticals are a bit like information and imagination transfusions. These breaks away from normal classroom and committee work give Hope academicians a boost to reinforce and revitalize their teaching and scholarship.

If not for her grandmother, Linda Dykstra, associate professor of music specializing in voice, may have never considered vocology as a field of inquiry in her academic life and thus for her sabbatical leaves from Hope in 2007 and 2015.

Though she had no way of knowing it as a child, Dykstra would eventually become fascinated with vocology — the science and practice of voice habilitation — in part due to her grandmother, whose voice was sacrificed as the result of an emergency tracheotomy performed by a country doctor at the site of an automobile accident in the 1930s. Her grandmother lived with a throat stoma for the rest of her life, and Dykstra’s compassion toward her grandma led to her curiosity about vocal folds (“They’re really not cords,” Dykstra clarifies) and how they work… and don’t work when mistreated by overuse or disease or disorder.

Because when one knows how something works, that’s when one knows how it can be fixed.

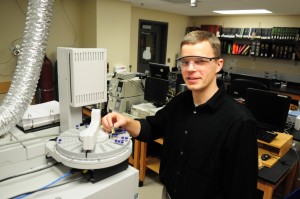

So Dykstra — a lyric soprano classically trained — spent much of her sabbatical “looking down throats at the office of ENT specialist Dr. Richard Strabbing (of Holland, Michigan), observing vocal disorders that resulted from laryngeal, tongue and thyroid cancers, vocal fold paralysis, and other considerably more benign disorders,” she says, in order to better understand the anatomy and function of these body parts essential to her teaching and voice therapy professions. This knowledge will help her better prescribe vocal singing techniques and therapies for Hope voice students who might, say, strain their voices over the summer as camp counselors or as Pull participants, both scenarios that she has worked with in the past.

Vocal fold knowledge will help Linda Dykstra better prescribe vocal singing techniques and therapies for Hope voice students who might, say, strain their voices over the summer as camp counselors or as Pull participants, both scenarios that she has worked with in the past.

“After the vocal folds sustain injury, and sometimes post-surgery, I provide habilitation techniques that can release muscle tension, aid in healing, and improve capacities to use the voice correctly,” says Dykstra whose post-graduate work in vocology has been cooperatively and collaboratively attained at the Keidar Voice Institute in New York City and the Bastian Voice Institute of Downers Grove, Illinois.

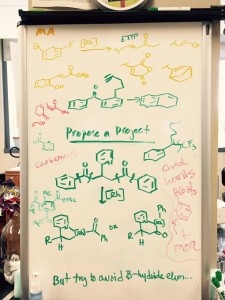

Also on her last two breaks away from the college, Dykstra invented and then “preached the gospel of SonoVu,” an audio-visual technology she pioneered (and for which she has a provisional patent) with the help from a Hope ACAT (Academic Computing Advisory Team) grant in 2006. SonoVu links video with an already-invented audio display software called VoceVista. Dykstra put the two mediums together in order to teach voice students both visually and aurally since SonoVu allows them to see acoustic feedback, mouth formation and posture all at the same time. Dykstra records the two outputs through SonoVu and then hands her voice students DVDs of their visual and audio selves for corrective or affirmative reference.

“Before SonoVu, I could not even program our VCR,” Dykstra laughs. “Now I’m working with other institutions to bring SonoVu to their voice studios.”

Working daily with her invention in her homey office inside the new Jack H. Miller Center for the Musical Arts, Dykstra always has plenty of company. Voice students not only fill her office most of the day for lessons, but she is also surrounded by numerous neatly-hung, black-and-white head shots of Hope graduates whom she has taught over the years and who now perform professionally across the country. Due to the flexible time sabbaticals provide, Dykstra took the opportunity to see two of those accomplished professionals perform in full color off-Broadway in New York City and in a Puccini opera in Des Moines, Iowa. Watching each perform on stage was a culminating joy, and it made Dykstra’s heart do what it knows best — sing.

—

Linda Dykstra is an associate professor of music in the Hope College Music Department.