The story of my first day in art class

My first day at l’Ecole de Beaux-Arts de Nantes, I got lost. After three levels of gray cement floors, catwalks, and metal railings, the only things that reassured me I was still in the right place were the eccentrically-dressed students and a mass at the entrance that slightly resembled a globe made out of tissue paper and a yoga ball. I was definitely in a Fine Arts building.

Finally, I pushed through a heavy white door into a gray room as balmy as a summer day. At the center sat an elderly man in nothing but a robe. Around him roughly ten men and women, the youngest at least 40 years my senior, unfolded easels and wagged around sheets of paper the size of cookie sheets.

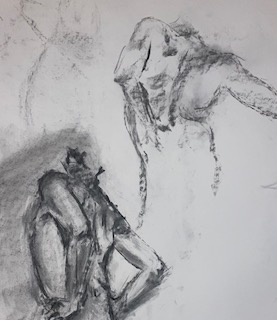

As the student next to me began arranging his sticks of chalk onto a tray beside us, meticulous as a surgeon preparing for operation, I suddenly felt as naked as the man in the robe. My humble sketchbook and mechanical pencil, the only tools that I had thought to bring, sat meekly before me. I was entirely unprepared. In a stroke of inspiration (desperation) I snatched a discarded scrap of charcoal off the coal-powdered floor. Thankfully the professor took notice of my lack of preparation and out of kindness (pity) donated a few sheets of paper to my easel. Thus began my first live-model sketching class at the Beaux-Arts school of Nantes.

When I tell people about my drawing class, one of the first questions they ask is, “Is it awkward?” The answer? At first. After all, it’s not everyday that I spend 30 minutes painstakingly analyzing a naked stranger. Only Tuesdays.

That first day, I saw a human. I saw wrinkles and lumps and caves. Most of my worry the first day didn’t even concern my sketching abilities, but rather if I would offend him by drawing an insecurity. Would I expose a wrinkle? Bring attention to his nose, his stomach? Soon, however, the person faded. What started as a human body, something judged and critiqued and compared, became shapes and light. A line, curved at the start. A square. An edge. A half moon. His body was the art, and became neutral and abstract as such. There was no good or bad, too big or too small. Just shapes and light.

By the time the professor stopped us all to turn our easels and view the works of our classmates, I felt calm. I did what I could with what I had. There is no right or wrong in art, I assured myself. And it was true. Walking among the other students, I was in awe of their skill. Each board presented the softness of a gray arm, streaks of muscle through leg, shadows cut into a stomach. I felt like yelling. Why aren’t these in a museum! But I don’t think they would have understood me.

I ended that first day exhausted. I trudged out of the studio into the night, fingertips dusted black with charcoal. But this exhaustion wasn’t the ‘go cry in the nearest bathroom’ type. I searched myself. My shoulders ached as I tramped across the bridge. My stomach was empty with reverence and hunger. It wasn’t until I took note of the strain in my eyes, still searching for residual shapes and shadows to scratch on a page, that I identified it. I felt eager. I felt enthusiastic. I felt proud.

Mostly, though, I noticed what I did not feel. Not once throughout the entire night did I feel self-consciousness. There was no room for judgment in a space of creativity. Only shapes and lines, shadows and art. I couldn’t wait to go back again.