I have long excelled at doing nothing. One of my favorite childhood pastimes was sitting on a riverside rock for hours upon end, whiling away the summer just watching the fish, frogs, and water voles cavort in the current.

Then adulthood came and I was expected to actually do things with my time, so that childhood habit fell by the wayside.

…Or at least, it did for a few years. Now it’s assigned for class.

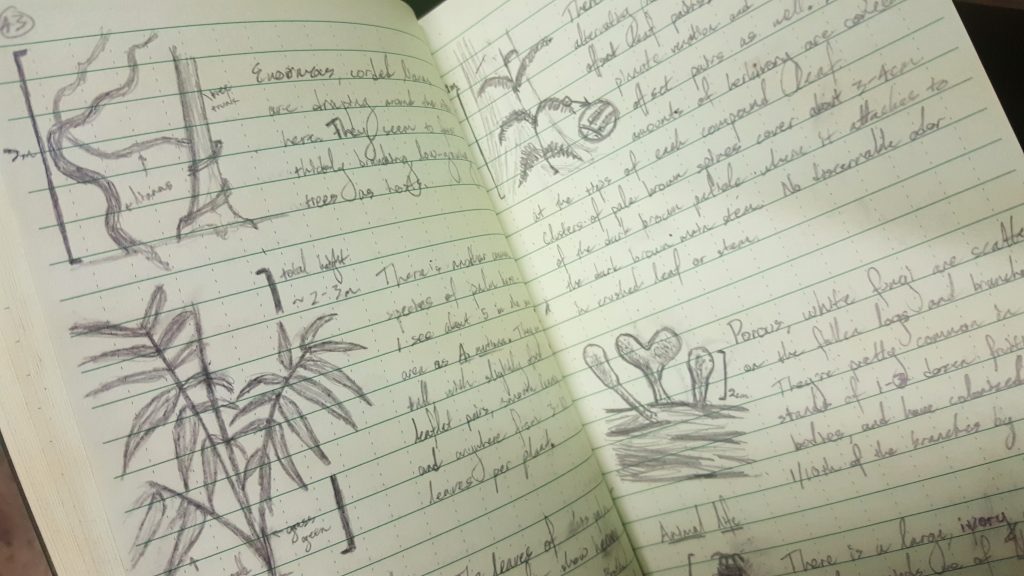

As part of our homework for the Fundamentals of Tropical Biology class, we students need to wade into the underbrush, have a seat for an hour, and catalogue everything we see, smell, and hear in that area. The exercise trains us to quickly notice the most important aspects of a local habitat and often prompts questions about the ecological interactions we perceive. That latter part reveals the other purpose of this exercise; it provides a sort of brainstorming process for the independent ecological research projects that will be our magnum opera of this semester.

I’ve thoroughly enjoyed completing these exercises in every major biome we visit, but our current location has provided the most interesting wilderness for exploration. We’re now staying at La Selva (“The Jungle”) Biological Station in northeast Costa Rica. There are nearly 4,000 acres of tropical rainforest held by this station, and there’s no lack of activity as the rainy season is just beginning to start in earnest. Life is everywhere you look!

For starters, these little guys—about the size of my last pinky joint—are perpetually underfoot! This is the aptly-named strawberry dart frog.

For starters, these little guys—about the size of my last pinky joint—are perpetually underfoot! This is the aptly-named strawberry dart frog.

If you’ll allow me to really get nerdy for a second: their scientific name is Oophaga pumilio, which is Latin for “dwarf egg eater” (pūmilio, oon, phagos). They won this moniker because the female carts the tadpoles up into the trees soon after hatching so that they can develop in the isolated, safe puddles of rainwater trapped by bromeliads and other tree-dwelling plants.1

The devoted strawberry dart frog mother then cares for her growing children by periodically stopping by these puddles and laying unfertilized eggs for them to eat. If she leaves them alone for too long, they’ll start splashing at the puddles’ surface to communicate their desire to feed on the proteins of their unfathered siblings.

Neat, huh?

I realize that the saga of Oophaga might not be appealing to everyone, so let’s move right along and check out this glasswing butterfly. Butterflies and moths have tiny scales on their wings which give them pattern and color, which you might have already found out if you ever tried touching one and a fine colorful dust rubbed off on your fingers. But the glasswing butterflies are special; their wing scales are modified into translucent hairs, so you can see straight through the wing frame! Their Spanish name is espejitos, or “little mirrors,” which is just plain adorable.

There are all sorts of amphibious critters to be found in the forest. This tree frog is cozied up with some thick epiphyll cover—that mossy growth on the leaf surface. He’s a nocturnal species, and is more than a little grumpy at being woken. I feel a special kinship.

This is the biggest damselfly I’ve ever seen, with an abdomen about four inches long. I think it’s Megaloprepus caerulatus, which boasts the largest wingspan of all damselflies (and even dragonflies) worldwide! They, like the dart frogs, raise their young in arboreal puddles called phytotelmata. Unlike the dart frogs, they lay all their eggs in one puddle and let the carnivorous young naiads murder and cannibalize each other until a few satisfied winners emerge and develop to adulthood. It’s lonely at the top.

The roots of the trees here seem as old and broad as the earth, and sport so much moss that they appear to be growing small forests of their own. The biodiversity here at every level is stunning, and I’m excited to spend the last weeks of this program surrounded by so much pure life.

A uniquely popular phrase here in Costa Rica is “pura vida!” or “pure life!” It can be used as a greeting, a farewell, or a philosophy. I think I’m finally beginning to understand.

So until next time,

¡Pura vida!