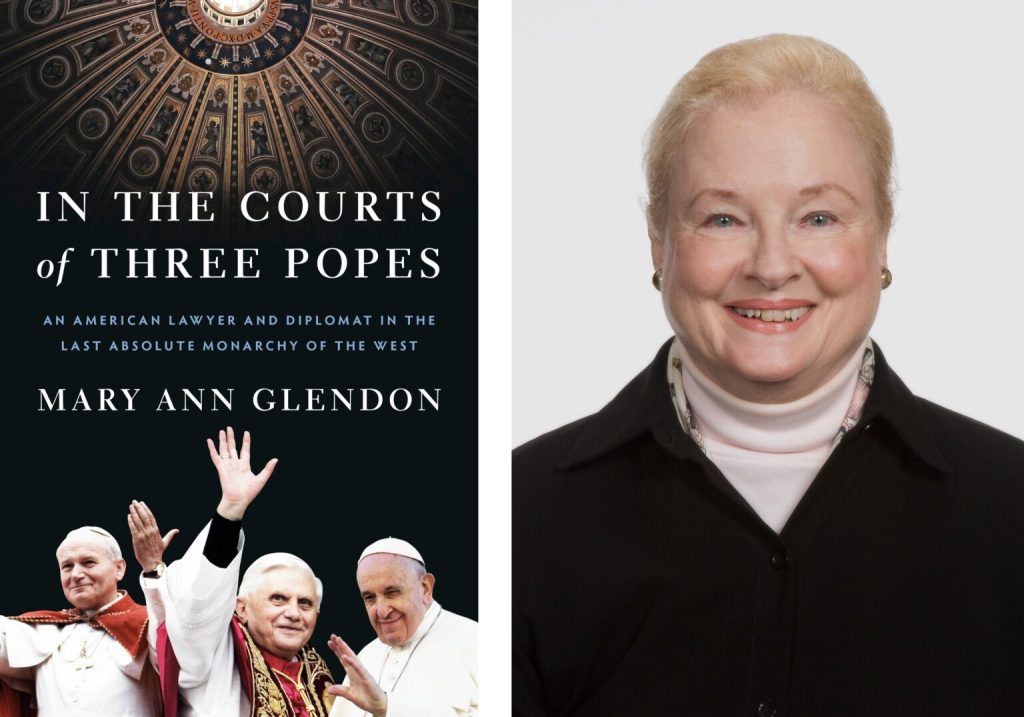

The Catholic Church and the leadership of the Pope on important social issues has gained more global attention in the last decade than ever before, especially in light of the astounding claims of clerical abuse against minors. Amidst this history, the Church has nevertheless stood the test of time. In a divisive society that is quick to draw boundaries based on race, gender, sexual orientation, religious beliefs, political alignments, and more, the Church has only strengthened its stance as a “global moral witness,”1 advocating for universal human rights, women’s rights, and religious freedom.2 Mary Ann Glendon, esteemed legal scholar, international lawyer, and diplomat, has dedicated years of service to the Roman papacy and the Catholic Church.3 As a Christian intent on pursuing a legal career, I found Glendon’s recent autobiography appealing. As I prepare to graduate and leave the familiarity of the Hope College community, I fear navigating how my faith will inform my work in the legal profession. Glendon’s story fascinated me as she directly incorporates her faith into her career in international law, exemplifying that the two need not exist independently. In In the Court of Three Popes: An American Lawyer and Diplomat in the Last Absolute Monarchy of the West, an autobiographical memoir, Glendon details her service in the courts of John Paul II, Benedict XVI, and Pope Francis. All three popes strived to modernize the Catholic Church in light of social issues and evangelize on an international scale. Glendon’s candor and vulnerability as she explores her triumphs and shortcomings during her service to the popes sheds light on the mysterious inner workings of the Catholic Church’s governing body while also highlighting the importance of carrying one’s faith into all spheres of life.

Glendon structures her memoir in three parts, describing her service in each court. John Paul II prioritized female empowerment4 and the responsibility of the laity during his papacy.5 There, Glendon served as a leader of the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences and leader of the Holy See delegation to the UN World Conference on Women. She received ample criticism about her qualifications as neither a man nor a prelate (a bishop or other high-ranking member of the Church). In the court of Pope Benedict, Glendon was appointed by President George W. Bush to serve as the U.S. ambassador to the Holy See and President of the Pontifical Academy. Many of the Pope’s speeches, texts, and initiatives centered around “human rights, religious freedom, and the synergy between faith and reason.”6 Finally, Pope Francis devoted significant energy to investigating the “scandal-ridden” Vatican Bank, which was assessed by a five-person committee on which Glendon served.7 Glendon examines her triumphs and shortcomings working alongside each pope. She played a role in crucial historical events for the Catholic Church, ultimately encouraging readers that one need not bear the title of a prelate to serve the body of Christ effectively and wholeheartedly.

Glendon used her unique position as an American laywoman in the papal courts to highlight the Catholic Church’s stance on equality and female leadership. Without demeaning the Church, she humbly acknowledges that, though the Catholic Church has made strides in terms of gender equality, more is needed. Glendon defines her career as one spent as a “stranger in a rather strange land,” where she served as “a layperson in a culture dominated by clergy, an American woman in an environment that was largely male and Italian, and a citizen of a constitutional republic in one of the world’s last absolute monarchies.”8 While societal breakdowns in traditional norms in the 1960s caused significant turmoil within the Catholic Church for clergy and laity, it also forced leaders to reconsider their stance on female leadership, opening the door for female diplomats like Glendon and clergywomen internationally. However, Glendon bravely intimates that the Catholic Church does not always treat women fairly behind closed doors. On one occasion, Glendon watched as a male consultant for the Vatican Bank was sworn to “pontifical secrecy,” a “time-honored ritual” she had never been privy to as a woman, even after serving three popes for nearly two decades at that point.9 This oversight was a microcosm of the inequitable treatment afforded to women “in a court with many lords and few ladies.”10 On another occasion, Glendon was excluded from an intimate dinner party with Pope John Paul II after her invite had been “forgotten” by one of her male peers, an archbishop serving in the Pope’s court.11 It was later revealed that many prelates at the time “were still in shock at the demise of the Italian papacy and resented the presence of foreigners in the Vatican,” especially women.12 Despite such humbling frustrations and setbacks, Glendon discourages readers from feeling disinclined if they wish to serve the Church.13 She articulates that the Church is not perfect but, in the words of Flannery O’Connor, has still “done more than any other force in history to free women.”14

Glendon does not shy away from the critical social issues the popes encountered, the most troubling being the “clerical sex abuse crisis and emerging financial scandals.”15 She neither glosses over the issue nor beats around the bush but faces it directly, as did her superiors. The most remarkable characteristic of the pontificate of the popes in their handling of these and other critical social issues is their commitment to allowing their faith and reason to inform each other rather than isolating social policies from faith. In 2000, as the Catholic Church prepared to enter the turn of the “third Christian millennium,” Pope John Paul II called for a “broad examination of conscience,” acknowledging the “mistakes and sins of Christians” in the past, remembering that the Church is “holy. . . but always in need of being purified.”16 In the midst of the “emerging sex abuse crisis” in 2001, John Paul II insisted that the Church “[approach] the twenty-first century on her knees,” taking “full, unequivocal responsibility for grave evils while continuing to affirm its own existence.”17 John Paul II also supported women’s rights through a lens of faith, claiming “the Christian faith gives no room for oppression based on sex.”18 Similarly, Glendon emphasized Pope Benedict’s exhortation to incorporate faith into the public square. Though the Pope and his court greatly opposed U.S. military action in Iraq, he praised American allegiance for “positive secularism.”19 He applauded American society for being the first to successfully establish and maintain a secular state “not out of antagonism toward religion but out of respect for it.” Through the pontificates, Glendon affirms that different views need not always give way to division. She suggests faith and reason can not only coexist but inform one another.

As a non-Catholic, I struggled with Glendon’s tendency to direct her writing towards a Catholic audience. She encourages “young Catholic women and men” concerned about the challenges facing the Church, to serve according to their skills and calling.21 Admittedly, as someone raised in the Baptist church, I possess only a general understanding of the beliefs and structure of the Catholic Church. Glendon writes under the assumption that her readers are well-acquainted with the intricacies of the Catholic faith. For example, though she explains that the “Holy See” is the governmental structure of the Catholic Church, she provides minimal definitions. Without a background in the Catholic Church, I found myself researching terms like encyclical and pontificate, the hierarchical structure of the global Catholic Church, and the history of Vatican City and the Vatican Council. Readers with limited knowledge of the Catholic Church may want to be aware of this angle.

Despite Glendon’s Catholic focus, her message highlighting the importance of the laity within the Church body resonated with me. Glendon suggests that the laities bear the primary responsibility for carrying out the Church’s mission of evangelization in the secular spheres where they live and work. Her hope is that “lay Catholics will find [her] account. . . helpful in their own struggles to be ‘salt, light, and leaven’ during a time of turbulence.”22 Her narrative further reinforces the significance of the laity. John Paul II admonished Glendon to rely on the Holy Spirit to be a “voice for the voiceless” wherever she traveled.23 The Catholic laity are encouraged to defend the Church even as its sins are revealed, aspiring to share the Gospel with “renewed vigor” rather than despairing.24 In the same way that Glendon relied on the Holy Spirit to advocate for women and children during the UN World Conference on Women, she encourages laypeople to demonstrate courage in their respective workplaces and communities. Glendon commends the Second Vatican Council’s call for the “hour of the laity” to spearhead the “evangelization of the modern world.”25 Glendon asserts that the challenge for the laity, not the clergy, has remained the same since Christ’s resurrection: to rise as the primary missionaries of the Church. While “the environment in which the mission must be carried out,” has evolved in response to “moral and religious ideas about sex, marriage, honor, and personal responsibility,” the call has not.26

I resonated with Glendon’s reminder that every member of the body of Christ, not just priests or bishops, have the responsibility to share the light of Christ. As a Christian, I believe that the Holy Spirit can inform me in any space, whether in the classroom, in lunch conversations, or in my future workplace as an attorney. This encouragement extends to all Christians, Catholic or Protestant, clergy or layperson, to share the light and love of Christ in word and deed. As Pope Benedict posits, the Catholic Church should act fraternally toward “every ecclesial community, and a sign of friendship for members of other religious traditions and all men and women of goodwill.”27 Believers ought to stand firm in their convictions while embracing every brother and sister made in the image of Christ.

As someone interested in exploring how faith informs law and policy, I appreciated Glendon’s efforts to reconcile the Catholic faith with her professional work in international law, feminism, and universal human rights. From the beginning of her career, Glendon has exemplified how to integrate faith and profession. During her interview at Harvard Law, Glendon presented the findings of her comparative study on abortion law, investigating how Western countries prioritized personhood, rights and responsibilities, and human flourishing through approaches to abortion, divorce, and economic dependency. Though she was aware “few people shared her interests and personal commitments,” she did not shy away from studying or sharing themes motivated by her faith convictions.28 During her service as the U.S. Ambassador to the Holy See, Glendon focused on resolving humanitarian issues, an area of common interest between the United States and the Holy See.29 With the support of Pope Benedict, she advocated that “intermediary institutions of civil society,” such as the Church, are more equipped to provide social services than the state since they are capable of “guaranteeing the very thing the suffering person. . . needs: namely love and personal concern.”30 Glendon’s convictions impacted her research and diplomacy, challenging the assertion that faith has no place in policy and law. Glendon’s work and influence serve as an example of how the church acts as a vessel for justice.

Glendon’s memoir is a thought-provoking read for those interested in the inner workings of the papal courts, how the Catholic Church advocates for social issues with principles rooted in Biblical teachings, or how faith informs the actions of believers within a secular space. Through her personal life and career, Glendon emboldens readers to become global, moral witnesses, “[investing] all our resources of intelligence and energy in serving the cause of the Kingdom,” knowing that “without Christ we can do nothing.”30

Maya Favor

Maya Favors ’26 is a political science and Spanish double major on the pre-law track. She is originally from Indianapolis, Indiana. She would like to thank Dr. David Ryden for his guidance on this review.

Footnotes

1 Mary Ann Glendon, In the Court of Three Popes: An American Lawyer and Diplomat in the Last Absolute Monarchy of the West (New York, Penguin Random House, 2024), 40.

2 Ibid. 40.

3 “Mary Ann Glendon,” Harvard Law School, accessed October 31, 2024, https://hls.harvard.edu/faculty/mary-ann-glendon/

4 Mary Ann Glendon, In the Court of Three Popes, 21, 25, 37.

5 Ibid. 40, 48.

6 Ibid. 121.

7 Ibid. 154.

8 Ibid. xii.

9 Ibid. xi.

10 Ibid. xi.

11 Ibid. 37.

12 Ibid. 38.

13 Ibid. 195.

14 Flannery O’Connor, qtd. Mary Ann Glendon, In the Court of Three Popes, 185.

15 Mary Ann Glendon, In the Court of Three Popes, 191.

16 Pope John Paul II, qtd. Mary Ann Glendon, In the Court of Three Popes, 46.

17 Ibid. 46, 49.

18 Ibid. 25.

19 Ibid. 110.

20 Ibid. 110.

21 Mary Ann Glendon, In the Court of Three Popes, 193.

22 Ibid. xii, xiv.

23 Pope John Paul II, qtd. Mary Ann Glendon, In the Court of Three Popes, 26.

24 Mary Ann Glendon, In the Court of Three Popes, 48, 50.

25 Ibid. 187.

26 Ibid. 188, 189.

27 Pope John Paul II, qtd. Mary Ann Glendon, In the Court of Three Popes, 109.

28 Mary Ann Glendon, In the Court of Three Popes, 17.

29 Ibid. 126.

30 Ibid. 126, 127.

31 Ibid. 197.