Books are not just stories—they are windows into different cultures, times, and experiences. While it’s easy to reach for familiar titles from your own country, reading classic books from other countries offers unique and rewarding insights. If you are interested in traveling or even just to know more about a country, choosing a classic or popular book from that country can be a great way to immerse yourself in the culture and history a bit more. If you are unsure where to start, here are some great books from various countries around the world that could be your next read!

North America:

Pedro Páramo by Juan Rulfo (Mexico)

A young man returns to his father’s village to fulfill his mother’s dying wish, only to find it eerily populated by ghosts and memories. The haunting narrative explores themes of loss, regret, and the intertwining of life and death.

Anne of Green Gables by L.M. Montgomery (Canada)

Anne Shirley, an imaginative and spirited orphan, unexpectedly finds a home with Marilla and Matthew Cuthbert in the picturesque setting of Prince Edward Island. The book follows Anne’s adventures and her journey of growth, acceptance, and friendship.

South America:

The House of the Spirits by Isabel Allende (Chile)

Spanning multiple generations, this magical realist novel chronicles the tumultuous history of the Trueba family and explores themes of love, power, and political upheaval. The story blends personal drama with social and political changes in Chile.

The Posthumous Memoirs of Bras Cubas by Machado de Assis (Brazil)

Brás Cubas, recently deceased, narrates his life story from the afterlife, presenting a whimsical and satirical view of 19th-century Brazilian society. His posthumous memoir is filled with dark humor and biting social commentary, examining themes of ambition, love, and mortality with a uniquely irreverent style.

Ficciones by Jorge Luis Borges (Argentina)

A collection of surreal and thought-provoking stories that explore the boundaries of reality, identity, and the nature of fiction itself. Borges’s work is known for its complex themes and innovative narrative structures.

One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez (Colombia)

This epic novel follows the Buendía family over several generations in the fictional town of Macondo, blending magical realism with political and historical commentary. It explores themes of love, solitude, and the cyclical nature of history.

Europe:

The Trial by Franz Kafka (Czech Republic)

Josef K. is arrested and prosecuted by a faceless bureaucracy for an unspecified crime, plunging him into a nightmarish world of absurdity and existential dread. The novel is a profound exploration of justice, guilt, and the human condition.

Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes (Spain)

A man influenced by chivalric tales sets out on a misguided quest to revive knight-errantry, accompanied by his faithful squire, Sancho Panza. This satirical story explores themes of reality, illusion, and the power of imagination.

Faust by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (Germany)

Dr. Faust, a learned scholar, makes a pact with Mephistopheles, trading his soul for unlimited knowledge and worldly pleasures. The story examines themes of ambition, redemption, and the struggle between good and evil.

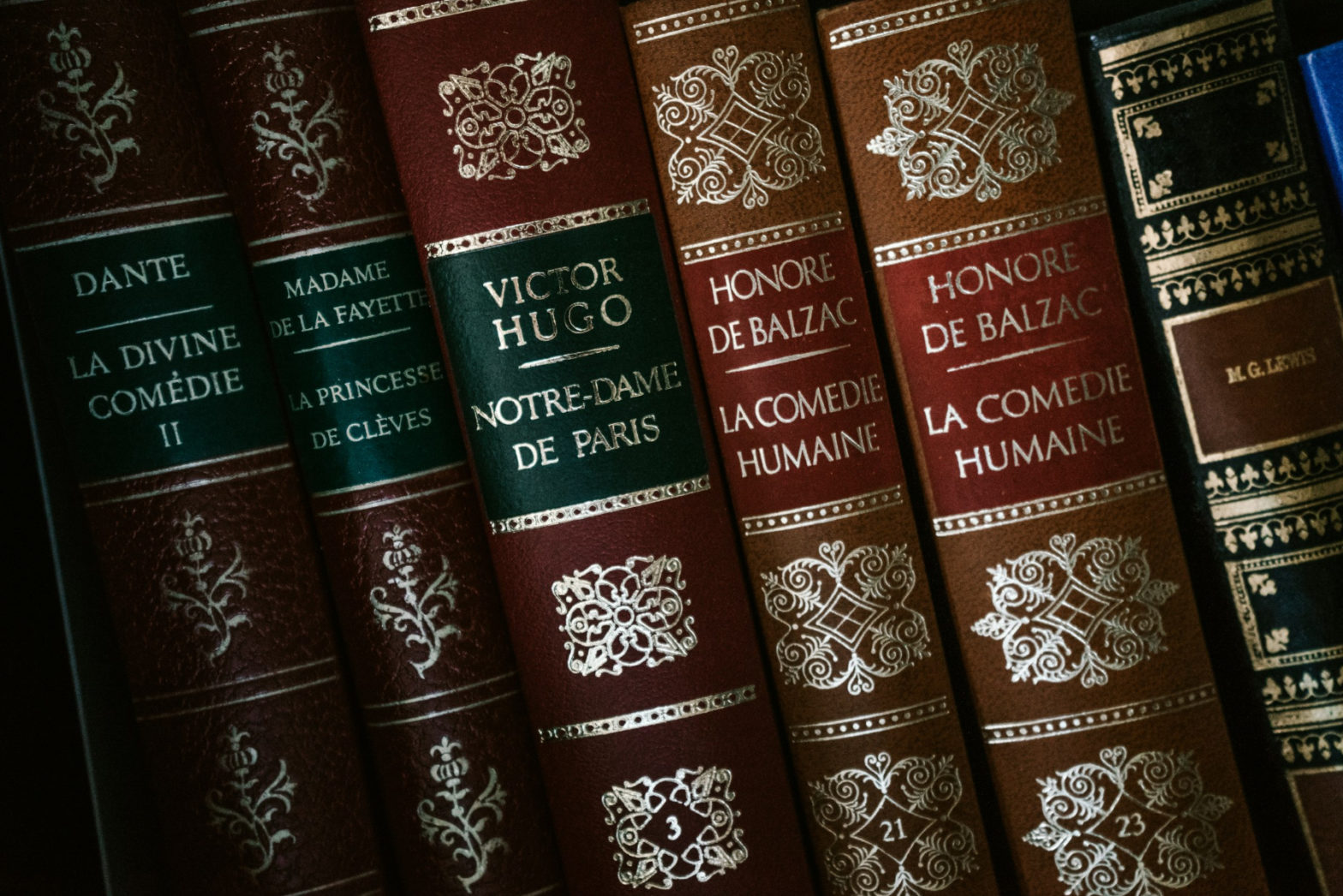

The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri (Italy)

Dante embarks on a journey through Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven, guided by Virgil and Beatrice, to understand the consequences of human actions. This epic poem is rich in symbolism, theology, and moral allegory.

Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen (United Kingdom)

Elizabeth Bennet navigates the societal pressures of Regency England while developing a complex relationship with the enigmatic Mr. Darcy. The novel humorously explores themes of love, marriage, and societal expectations.

Ulysses by James Joyce (Ireland)

Spanning a single day in Dublin, the novel follows Leopold Bloom and Stephen Dedalus in a modernist retelling of Homer’s Odyssey. Joyce’s groundbreaking narrative technique and dense references make it a challenging yet rewarding read.

The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas (France)

Edmond Dantès is wrongfully imprisoned and escapes to seek revenge against those who betrayed him, using a hidden treasure to change his fate. This epic tale explores themes of justice, vengeance, and redemption.

War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy (Russia)

Set during the Napoleonic Wars, the novel follows the intertwined lives of Russian aristocrats and examines the impact of war on society and individuals. Tolstoy’s sweeping narrative explores themes of history, power, and human relationships.

Africa:

So Long a Letter by Mariama Bâ (Senegal)

Written as a letter to a friend, the novel recounts the life of a Senegalese woman dealing with the aftermath of her husband’s death and his polygamous second marriage. It addresses themes of love, loss, tradition, and feminism.

Weep Not, Child by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o (Kenya)

In post-colonial Kenya, a young boy, Njoroge, struggles with the violence and upheaval caused by the Mau Mau Uprising. The novel explores themes of colonialism, identity, and the quest for education and liberation.

Nervous Conditions by Tsitsi Dangarembga (Zimbabwe)

Tambu, a young girl from a rural village, pursues education despite family and societal pressures. The book delves into issues of gender, race, and colonialism in Zimbabwe’s pre-independence era.

The Cairo Trilogy by Naguib Mahfouz (Egypt)

Following a Cairo family across three generations, the trilogy explores the evolving political, social, and religious landscape of 20th-century Egypt. Mahfouz captures the complexities of family dynamics and societal transformation.

Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe (Nigeria)

Set in pre-colonial Nigeria, the story follows Okonkwo, a powerful warrior, as European colonizers and Christian missionaries change his community. Achebe explores the clash between traditional African culture and colonial influence.

Cry, the Beloved Country by Alan Paton (South Africa)

In apartheid-era South Africa, Reverend Kumalo searches for his missing son in Johannesburg, discovering the racial injustices that divide his country. The novel is a poignant exploration of racial segregation and the quest for reconciliation.

Season of Migration to the North by Tayeb Salih (Sudan)

Returning to Sudan after studying in Europe, a young man encounters the enigmatic Mustafa Sa’eed, whose mysterious past reveals the dark consequences of colonialism and cultural assimilation. The story reflects themes of identity, power, and cultural conflict.

Asia:

The Tale of Genji by Murasaki Shikibu (Japan)

Considered one of the world’s first novels, it tells the story of Genji, a nobleman and his romantic escapades in the Heian court. The work offers rich insights into Japanese culture, courtly life, and human emotions.

The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini (Afghanistan)

Amir, a young boy from a privileged background in Afghanistan, befriends Hassan, the son of his father’s servant, but an event changes their lives forever. The novel explores themes of friendship, betrayal, redemption, and the impact of historical events on personal relationships.

The God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy (India)

In Kerala, India, twins Rahel and Estha navigate a childhood filled with family secrets, societal constraints, and the tragic consequences of forbidden love. Roy’s novel deftly explores complex themes of caste, love, and betrayal.

Dream of the Red Chamber by Cao Xueqin (China)

This classic Chinese novel captures the lives, loves, and tribulations of the Jia family, exploring themes of familial duty, romantic entanglements, and the complexities of social hierarchy. It is known for its rich detail and deep character exploration.

Australia/ Oceania:

My Brilliant Career by Miles Franklin (Australia)

Sybylla Melvyn, a young woman in rural Australia, dreams of becoming a writer and resists societal pressures to marry and conform to traditional roles. The novel is a strong feminist statement exploring themes of independence and ambition.

The Bone People by Keri Hulme (New Zealand)

A reclusive artist named Kerewin Holmes forms an unlikely bond with a mute boy, Simon, and his troubled foster father, Joe. The book explores themes of love, identity, and healing, set against the backdrop of New Zealand’s Maori culture