By Hannah Lever

Getting students and people of all ages engaged in books is not simply about a mastery of the mechanics of letters, words, and sentences. Reading is a valuable skill and a fulfilling hobby because human beings are created to create, to understand the world around us, and tell stories. We don’t read books only to improve our language processing skills or familiarize ourselves with grammar, we read to connect with our people, but to step outside of ourselves and to understand ourselves more completely.

When selecting literature to read, one aspect to consider is the idea of windows, mirrors, and sliding glass doors. What this metaphor means is that some texts will be windows for readers to understand experiences different than their own, some texts will reflect the experiences of readers and provide insight into themselves, and others will invite readers to step outside their understanding of the world and expand it. Often this metaphor is used to explain how including books with a wide range of subjects is beneficial for all students. What texts are windows or mirrors will differ between readers, but ideally every book will invite readers into their world and so should be sliding glass doors. The trouble comes when we realize that some readers have more mirrors than others.

Often the fiction taught in schools and the majority of books in school libraries tends to feature the experiences of white people, men, and abled bodied people. This is inequitable to readers who don’t fight into these majority categories because they are denied works that reflect them, but also unfair to readers who do fall into these categories because they have few texts that can be windows and are denied the development of skills that come with reading to empathize and open their minds. A promising solution to this problem may be graphic novels.

Graphic Novels as a Tool for Inclusion

For a variety of reasons, graphic novels tend to showcase more diversity—both in terms of identities and experiences but also subject matters—than traditional novels, especially what’s dominating the best sellers lists for middle and high school readers. This may be because as a newer media, there are less traditions and standards to follow, so the graphic novel has so much room to grow and show all that the media can represent. Or it might be because the publishing industry is prioritizing graphic novels as it becomes more intentional about including diversity both in terms of what’s on the page and who’s writing the pages. Or maybe this media that has been dismissed and pushed to the fringes of literature for decades, attracts writers and artists who feel like outcasts in society. Either way, graphic novels are a valuable tool for showing that all students are welcomed in the class not just because of the quantity of windows and mirrors available but the quality.

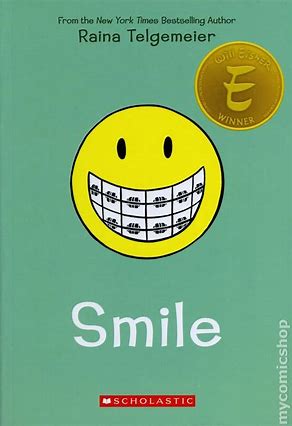

My little sister was absolutely devastated when she got braces, crying in the car on the way home because she was terrified that the kids in her class would make fun of her. My stories about how I had braces too and the teasing at school really wasn’t that bad did nothing to make her feel better. A few days later she came home from the school library with Smile by Raina Telgemeier, finally grinning and showing off her teeth and braces as she showed me the main character doing the same.

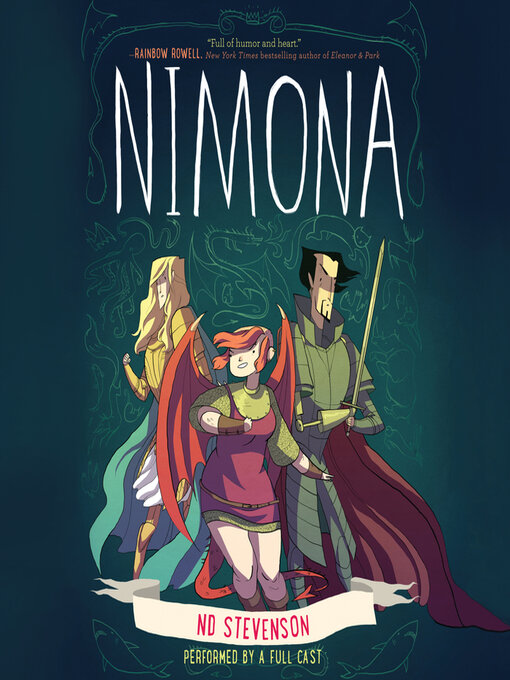

When I was a teenager, I was no different than other kids my age. I was trying to find my sense of self, but it felt shifting, always slipping through my fingers the minute I felt like I had a hold of it. I read countless books, looking for a character that felt like I did, but it wasn’t until I read Nimona by ND Stevenson that I felt seen. Something about seeing the main character shift between wolf to girl to dragon to countless other things, all in bright pink, made me feel understood in a way that no other book could. A picture is worth a thousand words, but sometimes pictures say things that words could never.

Whether I’m in a school, library, or bookstore, I see this same thing happening in readers of all ages. You can’t truly understand the power of graphic novels until you see children pick up a book and see their eyes light up as they open the pages and point to a character inside and whisper to themselves, “they look like me.” And suddenly they are invited to step through a sliding glass door into the world of literature.

Not only do graphic novels offer an opportunity for readers to see themselves in a way completely unique to the media, I am also seeing the start of a shift in how graphic novels can be a vital tool to make readers feel heard as well as seen. Schools in Michigan and throughout the United States are seeing an increase in students who don’t speak English as their first language, often referred to as multilingual learners or English language learners (ELLs).

Many teachers struggle to engage these students in the classroom, especially when it comes to reading. One strategy some us is to provide translated materials—this is certainly an effective way to communicate to students the material as well as show they are welcomed in the classroom—but one drawback is that it creates a barrier between the main language used in the classroom and the primary language of the student. Most students get English texts and the ELL gets the text in their native language and the two languages don’t mix, the native language being slowly phased out in favor of English.

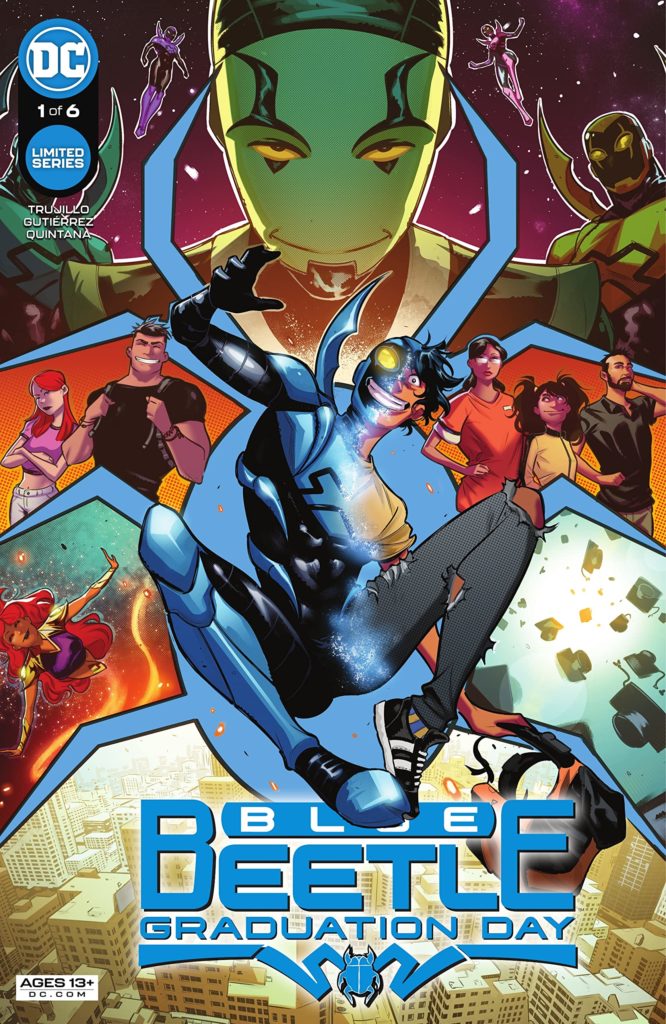

I recently read a comic book (and if all the issues of the comic were bound in a traditional book it would be called a graphic novel) called Blue Beetle: Graduation Day by Josh Trujilloand and was fascinated by its use of language. Typically, in comics and graphic novels, to show that a character is speaking a different language, their speech bubbles will be put in brackets with a little note at the bottom of the page that their language has been translated into English for the reader’s convenience. Blue Beetle made the bold choice not to do this, instead keeping the Spanish that the main character, Jaime Reyes, and his family speak untranslated.

This shows the power of graphic novels as a tool for developing reading skills because what the characters are saying can be inferred from the illustrations if the reader isn’t familiar with Spanish. But the opposite is true as well, if the reader only knows Spanish, they can infer the meaning of the English words through illustrations. If this work was used in a classroom with a Spanish ELL student, they can feel a sense of mastery because they have the precise meaning of the Spanish text as well as feel more comfortable in their understanding of the English text. In addition to this, students whose primary language is English are learning just as much language skills as the ELL students.

I’d argue that the most important impact of a text like this is showing ELL students that they belong in the classroom and that the language they speak and read is valuable. Not only do Jaime and his family, the Mexican American Immigrants, speak Spanish in this comic, but so does Superman, a symbol of American identity. Symbols have power and now more than ever are students plugged into pop culture, so graphic novels present an invaluable opportunity to engage readers, connect with them through pictures and language that reflects them, and tell them they belong.

Hannah Lever is a senior at Hope College studying English secondary education and has been an avid reader of all things, especially comics and graphic novels, for as long as she could read.