By Jonathan Hagood

One of the most important goals for all students who enroll in a college or university is to graduate—and the pomp and circumstance that make up the commencement ceremony. This is an august, solemn, and weighty occasion. It can also, for those of us who attend every year, be quite boring. I’ve seen colleagues grade papers, read journals and books, catch some screen time, nap… we also share stories about students (treasured and not) and cheer on those we knew well as their names are called and they walk across the stage. Still, the gap in time between students that I know can be long. What to do both to pass the time and to stay focused…?

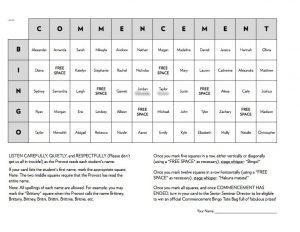

I started playing Commencement Bingo four years ago, and it’s now an expected and cherished tradition at my school. Here are the basics:

- An 8-1/2” x 11” sheet of cardstock has a grid of sixty squares: the five letters in BINGO multiplied by the twelve letters in COMMENCEMENT.

- Each square has a randomly selected first name, drawn from the most frequently occurring names in the graduating class.

- Six of the squares are marked as a FREE SPACE.

- I do all of this in Excel, and I randomize the squares, making 25 distinct versions of the card (it’s more fun if your neighbor’s card has a different arrangement of names).

- A sheet of 55 stars—Avery® Assorted Foil Star Labels 6007 (http://www.avery.com/avery/en_us/Products/Labels/Identification-Labels/Foil-Star-Labels_06007.htm)—accompanies each card.

- When a first name is read aloud, you mark the appropriate square with a star.

It’s relatively simple—and fun! My colleagues and I find that playing Commencement Bingo not only passes the time, but we also pay more attention to the names of students as they are called. In addition, I find myself reflecting on and remembering particular students whose first names I have on my sheet. For example, in the Class of 2017 one of the most frequent names is Elizabeth, and I thought about the many Elizabeths, Lizzes, Beths, etc. that I have taught both recently and over the years. Waiting for a relatively rare name can also lead to cheering from the faculty. For some reason this year it took a while for a Justin to walk across the stage, but when he did several faculty members who had been eagerly awaiting the opportunity to star a Justin-square on their cards cheered. Someone next to me said, “I bet Justin’s wondering why the faculty are so happy for him.”

Over the years I’ve learned some necessary tweaks. The card originally started as a 5×5 grid, but that was not enough to last through our 700+ students. Even expanded to 5×12, many faculty finished “too soon.” So, I added the feature of having two squares with the full names of students I knew would be at the end of the ceremony. At our school, those are students graduating with a Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN). That way, every player has to wait until the end of Commencement to finish. This year, I realized that there is still a gap between filling out the first-name squares and waiting for the nurses. So, next year I plan to add squares for full names of students that I know will be in the last third of the ceremony (for us, students receiving Bachelor of Music or Bachelor of Science degrees). I think I might also add some open-ended, but personal squares, like “One of Your Advisees” or “Student You Knew Well.”

I have also added an element of winning prizes. Players who write their names on their cards and turn them in to me are entered into a drawing for a tote bag with swag inside. The bag is labeled “Commencement Bingo,” and my hope is that over the years it becomes a hot commodity.

I have also added an element of winning prizes. Players who write their names on their cards and turn them in to me are entered into a drawing for a tote bag with swag inside. The bag is labeled “Commencement Bingo,” and my hope is that over the years it becomes a hot commodity.

Because I am a history professor, on the back of the card I provide some interesting data. I list the top 50 names for the graduating class (Class of 2017), the top 15 baby names for the years in which they were born (1994-96), the top 15 baby names for 100 years before (1884-86)—I don’t see a lot of Franks or Ethels in my classrooms these days, and the top 15 baby names for last year (the Class of 2038?). I also included an article from our student newspaper re: the graduating class of 1917: “Seniors on Wild Rampage of Festivities: Celebrate With Two Parties In Last Week of School” (http://digitalcommons.hope.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1021&context=anchor_1917). I’m not sure as many of my colleagues enjoy this side of the card as much I do, and so next year I think I might add a Commencement Crossword Puzzle. Lots of opportunities there.

Does playing bingo take away from the augustness, solemnity, and weight of the commencement ceremony? I don’t think so. I hope not. There are certainly folks who decline to play, but I’ve yet to hear anything negative from administrators above my pay grade—in fact, more than one of them have given me positive feedback. One of my colleagues told me that she shared knowledge of this faculty “tradition” with her students and reported that they all thought it was great fun. That said, I am sensitive to folks who might think otherwise. I know of at least one colleague who has told me that she doesn’t think it is appropriate and therefore does not participate. Returning to where I started, I’d like to think that it helps me to focus and think about the students. I would also argue that playing bingo honors the students and the occasion more than does grading papers, reading, checking social media, or napping. If anything, Commencement Bingo contributes to the merriment and celebration that should rightly accompany the gravity of the situation. Yes, our students have accomplished much, and this is a serious moment. It is also a time to smile, laugh, clap, and cheer.

Bingo!

I’ve also had some really unique opportunities as a teacher. While spending a semester at the University of Aberdeen my junior year, I was bit hard by the travel bug and a few years after graduation I was hit with a desperate need to get out of the country. Unfortunately, the downside to teaching is that it’s not the most lucrative field and travel is expensive. Luckily I discovered a company that did tours for students and decided to give it a try. It’s fantastic! Traveling with students is amazing- getting to watch them experience firsthand what they learned in school is the ultimate teacher/history nerd high. I’ve done four tours with students- one to Greece and China and two to Italy (and I’m taking another group back to Italy this summer).

I’ve also had some really unique opportunities as a teacher. While spending a semester at the University of Aberdeen my junior year, I was bit hard by the travel bug and a few years after graduation I was hit with a desperate need to get out of the country. Unfortunately, the downside to teaching is that it’s not the most lucrative field and travel is expensive. Luckily I discovered a company that did tours for students and decided to give it a try. It’s fantastic! Traveling with students is amazing- getting to watch them experience firsthand what they learned in school is the ultimate teacher/history nerd high. I’ve done four tours with students- one to Greece and China and two to Italy (and I’m taking another group back to Italy this summer).

Seeing his work in person gave me a newfound appreciation of Ai as an artist. His versatility—mastery of both traditional art forms and digital media, as well as many genres in between—is even greater than what I previously read about him. Seeing the actual artworks, and not merely pictures of them, brought the man’s creative gifts to the fore. The visual arts “speak” eloquently where words fail.

Seeing his work in person gave me a newfound appreciation of Ai as an artist. His versatility—mastery of both traditional art forms and digital media, as well as many genres in between—is even greater than what I previously read about him. Seeing the actual artworks, and not merely pictures of them, brought the man’s creative gifts to the fore. The visual arts “speak” eloquently where words fail. One of my favorite installations at the exhibit was a pile of ceramic river crabs—each one skillfully crafted, inviting the viewer to a feast of sorts. River crabs are a treat in Chinese cuisine. Ai invited his fans in November 2010 to a party featuring river crabs upon learning that the authorities of Shanghai were going to demolish his newly built studio in a village near Shanghai. The destruction of the studio occurred in January 2011. The crabs, long digested by now, were an “eat-and-tell” commentary on the Chinese government’s motto of promoting social “harmony”—héxié—which sounds almost the same as river crabs—héxiè. The ceramic ones, of course, continue to “speak” in protest against the arbitrary powers of the Chinese state wherever they are exhibited.

One of my favorite installations at the exhibit was a pile of ceramic river crabs—each one skillfully crafted, inviting the viewer to a feast of sorts. River crabs are a treat in Chinese cuisine. Ai invited his fans in November 2010 to a party featuring river crabs upon learning that the authorities of Shanghai were going to demolish his newly built studio in a village near Shanghai. The destruction of the studio occurred in January 2011. The crabs, long digested by now, were an “eat-and-tell” commentary on the Chinese government’s motto of promoting social “harmony”—héxié—which sounds almost the same as river crabs—héxiè. The ceramic ones, of course, continue to “speak” in protest against the arbitrary powers of the Chinese state wherever they are exhibited.

you think your college prepared you to succeed in law school?” It seemed pretty clear the interviewer from my top choice law school did not believe Hope College prepared me for a competitive environment.

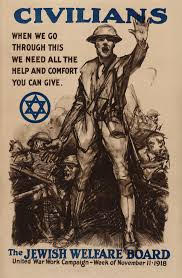

you think your college prepared you to succeed in law school?” It seemed pretty clear the interviewer from my top choice law school did not believe Hope College prepared me for a competitive environment. For one, the war forced Americans to face how diverse their society had become. Since the Civil War, over 20 million immigrants had come to the United States, making up 15% of the population. Native-born troops found themselves fighting alongside immigrants from 46 nations. Officials also had to confront the greater religious diversity as they built the army. At first, the War Department asked the Protestant Young Men’s Christian Association to provide recreation services to the troops, but they received complaints from Catholics and Jews, who argued that large percentages of the soldiers, particularly the nearly 20% who were immigrants, were not Protestant. To accommodate this religious diversity, the military allowed the Knights of Columbus, and the Jewish Welfare Board to also have recreational facilities.

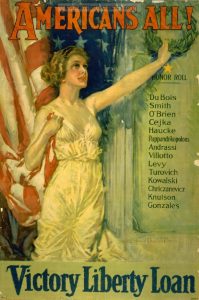

For one, the war forced Americans to face how diverse their society had become. Since the Civil War, over 20 million immigrants had come to the United States, making up 15% of the population. Native-born troops found themselves fighting alongside immigrants from 46 nations. Officials also had to confront the greater religious diversity as they built the army. At first, the War Department asked the Protestant Young Men’s Christian Association to provide recreation services to the troops, but they received complaints from Catholics and Jews, who argued that large percentages of the soldiers, particularly the nearly 20% who were immigrants, were not Protestant. To accommodate this religious diversity, the military allowed the Knights of Columbus, and the Jewish Welfare Board to also have recreational facilities. The nation’s growing diversity also became an issue at home. Some leaders, like Theodore Roosevelt, argued that immigrants had to reject “the hyphen” and prove themselves to be “100% American.” German Americans felt the brunt of suspicion as native-born Americans went to far as to purge German words from their vocabularies. For instance, sauerkraut became known as “freedom cabbage.” Yet the Wilson administration knew that they could not alienate immigrants, and they used propaganda to promote their inclusion into American civic life. One poster, titled “Americans All.” had an image of Lady Liberty and an “honor roll” of Irish, Italian, Slavic, Scandinavian and other ethnic names (although not German). Many immigrants embraced the opportunity to prove their love of the nation by enlisting in the Army, participating in Liberty Loan campaigns, and volunteering for the Red Cross.

The nation’s growing diversity also became an issue at home. Some leaders, like Theodore Roosevelt, argued that immigrants had to reject “the hyphen” and prove themselves to be “100% American.” German Americans felt the brunt of suspicion as native-born Americans went to far as to purge German words from their vocabularies. For instance, sauerkraut became known as “freedom cabbage.” Yet the Wilson administration knew that they could not alienate immigrants, and they used propaganda to promote their inclusion into American civic life. One poster, titled “Americans All.” had an image of Lady Liberty and an “honor roll” of Irish, Italian, Slavic, Scandinavian and other ethnic names (although not German). Many immigrants embraced the opportunity to prove their love of the nation by enlisting in the Army, participating in Liberty Loan campaigns, and volunteering for the Red Cross. During this time, the decades-long fight for women’s suffrage reached a crescendo. Some women took militant action, such as when Alice Paul chained herself to the White House gates and compared Wilson’s anti-suffrage stance to the oppression of the German Kaiser. Other activists, like Elizabeth Cady Stanton, argued that wartime service proved that women deserved full civil rights. Woodrow Wilson became convinced, and on September 30, 1918, he backed women’s suffrage, declaring, “we have made partners of the women in this war…Shall we admit them only to a partnership of suffering and sacrifice and toil and not to a partnership of privilege and right?” Congress passed the 19th Amendment a year later, and on August 18, 1920, it was finally ratified.

During this time, the decades-long fight for women’s suffrage reached a crescendo. Some women took militant action, such as when Alice Paul chained herself to the White House gates and compared Wilson’s anti-suffrage stance to the oppression of the German Kaiser. Other activists, like Elizabeth Cady Stanton, argued that wartime service proved that women deserved full civil rights. Woodrow Wilson became convinced, and on September 30, 1918, he backed women’s suffrage, declaring, “we have made partners of the women in this war…Shall we admit them only to a partnership of suffering and sacrifice and toil and not to a partnership of privilege and right?” Congress passed the 19th Amendment a year later, and on August 18, 1920, it was finally ratified.

Last summer, when I heard about the grand reopening of the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Museum and the new Devos Learning Center, I knew I had to learn more. I made a visit to the museum, and while there, I had the opportunity to meet with the museum’s education specialist, Barbara McGregor. I expressed interest in volunteering at the museum throughout the summer, but Barbara had a better idea. She was in need of support to prepare for the launch of the new learning center and offered me a special internship. As a student pursuing a degree in secondary education with a focus on history and political science, it was an incredible offer, and I asked how quickly I could start.

Last summer, when I heard about the grand reopening of the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Museum and the new Devos Learning Center, I knew I had to learn more. I made a visit to the museum, and while there, I had the opportunity to meet with the museum’s education specialist, Barbara McGregor. I expressed interest in volunteering at the museum throughout the summer, but Barbara had a better idea. She was in need of support to prepare for the launch of the new learning center and offered me a special internship. As a student pursuing a degree in secondary education with a focus on history and political science, it was an incredible offer, and I asked how quickly I could start.