Just to the east, just beyond the beach and into the dunes is a place that Suzanne DeVries-Zimmerman likes best about the Lake Michigan shore. Fewer footprints can be seen there, but life is actually more abundant. The terrain is less flat but just as sandy. And once she and the four Hope geology students with whom she conducts research step their feet off the shoreline’s beaten path, they find rolling sanctuaries of beauty and biodiversity. For it is there, in the interdunal wetlands along the big lake’s coast, that DeVries-Zimmerman and her students have plans to help conserve sands for time and life.

It’s not a bad gig if you can get it, working at a beach in the summer. DZ, as her students affectionately call her, is quick to admit that. The scenery and commute never get old even with three pounds of sand in their shoes, or when the temperatures climb into infernal degrees. Walking into the interdunal wetlands of the Saugatuck Harbor Natural Area — with permission from the local municipality and Land Conservancy of West Michigan — is quite a hike when laden down with research equipment, but “who wouldn’t want to spend a day here?” asks DeVries-Zimmerman, sweeping her right arm out over the landscape. “I covet this land,” she goes on to confess. But not as her own. DeVries-Zimmerman wants to maintain these areas for generations of plants and animals, insects and birds, as well as humans, to come.

“Our research aims to better understand how these interdunal systems work,” explains DeVries-Zimmerman, adjunct assistant professor of geological and environmental sciences. “They have not been well studied and they are ecosystems in danger in Michigan. Where these areas can develop and thrive along the lakeshore is somewhat limited. But we find huge biodiversity in them and that is very valuable to us all, not just the plants and creatures who live there.”

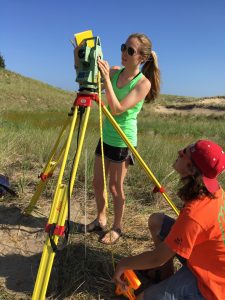

Put in peril by development and the drastically changing water levels of Lake Michigan, the interdunal wetlands are needed for migrating birds and butterflies, and for winter residents such as the predatory snowy owl. Western chorus frogs love to sing their songs in them and the yellow-flowered St. John’s wort favors the edge of the area’s low-lying pools to “keep their feet wet.” The wind-scoured depressions grow numerous wetland plant species such as beak rush, ferns, swamp rose, blue vervain, and steeplebush. Marram, horsemint, puccoon and Pitcher’s thistle, the latter a native plant that can only be found in Great Lakes dunes, grow in the sands away from too much water. By conducting topographical and ecological surveys, DeVries-Zimmerman, senior Jennifer Fuller, junior Dane Peterson, senior Benjamin VanGorp and senior Alexandria Watts are finding out more about the hydrology of the wetlands, how those areas are affected by the fluctuating lake levels, and how, in turn, that impacts the communities of flora and fauna uniquely therein. That is this dune crew’s interdisciplinary mission and passion.

“I find it fascinating how the dune species are so finely adapted to sections within the dune system,” says Watts. “Depending on the fluctuation of a couple centimeters, the plants have the ability to outline pools and ridges providing a pretty accurate picture of the topography of the area. I suppose there is almost something secretive or special that certain species can tell so much more than just being a green thing. They make me feel like a detective and you have to have a trained eye to see the clues.”

Significant funding secured from the Michigan Space Grant Consortium, the Jacob Nyenhuis Summer Faculty-Student Collaborative Development Grants, the Ver Hey Geology Summer Research Fund, and the Joyce Fund for Environmental Research has given DeVries-Zimmerman, her students, and three other Hope professors studying the dunes — Dr. Edward Hansen, Dr. Brian Bodenbender, and Dr. Brian Yurk — ample opportunities to learn more about dunes and dune management, even in England and Wales. This summer, the group spent three weeks at Liverpool-Hope University and along England’s Sefton Coast and Wale’s northern coast, learning how the British manage their dunes while initiating collaborative dune research projects in the process.

“The trip to England was a unique experience in that their dune management process has been far more involved in comparison to Michigan. There’s so many more factors at play in England’s dunes and interdunal wetlands,” Fuller points out. “Not only do they have the Atlantic Ocean seawater and weather to contend with, but a much longer history of human interactions. We met and worked with professors that have created methods of studying sand dune habitats, and their geomorphological movement throughout history using aerial imagery. They have already implemented ways of reopening dunes that have been over stabilized and established new management practices based on their findings. We left with many ideas, and perhaps even more questions about how the differences in our dune ecosystems will affect the way we need to take care of our dunes back home.”

Each student appreciates their research with DeVries-Zimmerman for the impact it will have on their future as well as for the fun they having now. Of their prof, they proclaim to have found a mentor full of knowledge and joy for her work.

“The most interesting thing for me this summer has been all of the new techniques and methods that I have been able to engage with and use,” declares Peterson. “I’m learning how to use different computer programs for mapping and comparison; I learned how to set up and run a surveying station; and, I’ve learned how to use pole aerial photography to obtain the information that I want.”

Adds VanGorp, “The part I love most working with DZ is how incredibly smart she is while also still having a great sense of humor. There is never a boring day in the field with her.”

“The early (dune) management thinking was to stabilize dunes. The thinking was the only good dune is a stable dune, but that’s not the right management model anymore. We want some dunes to continue to migrate so ecological succession can occur.”

Having researched Lake Michigan dunes with her three aforementioned professorial colleagues for over a decade now, DeVries-Zimmerman says they are still finding out “how much we don’t know” about the dunes and wetlands. They do know, though, that dunes must be allowed to move — if even a little — in order for biodiversity to thrive. “The early (dune) management thinking was to stabilize dunes. The thinking was the only good dune is a stable dune, but that’s not the right management model anymore. We want some dunes to continue to migrate so ecological succession can continue to occur.”

So, the woman who has loved the wetlands and dunes since she was a small child growing up in Holland, Michigan, will continue to keep her eyes on the sand. The winds will blow, water will rise and fall, and the finest grains of earth will grow and sustain a delicate natural order. And as it all does, DZ will remain just offshore, both at Hope and along Lake Michigan, for the sake of her students’ education and the sustainability of ecosystems made possible by wet and moving dunes.