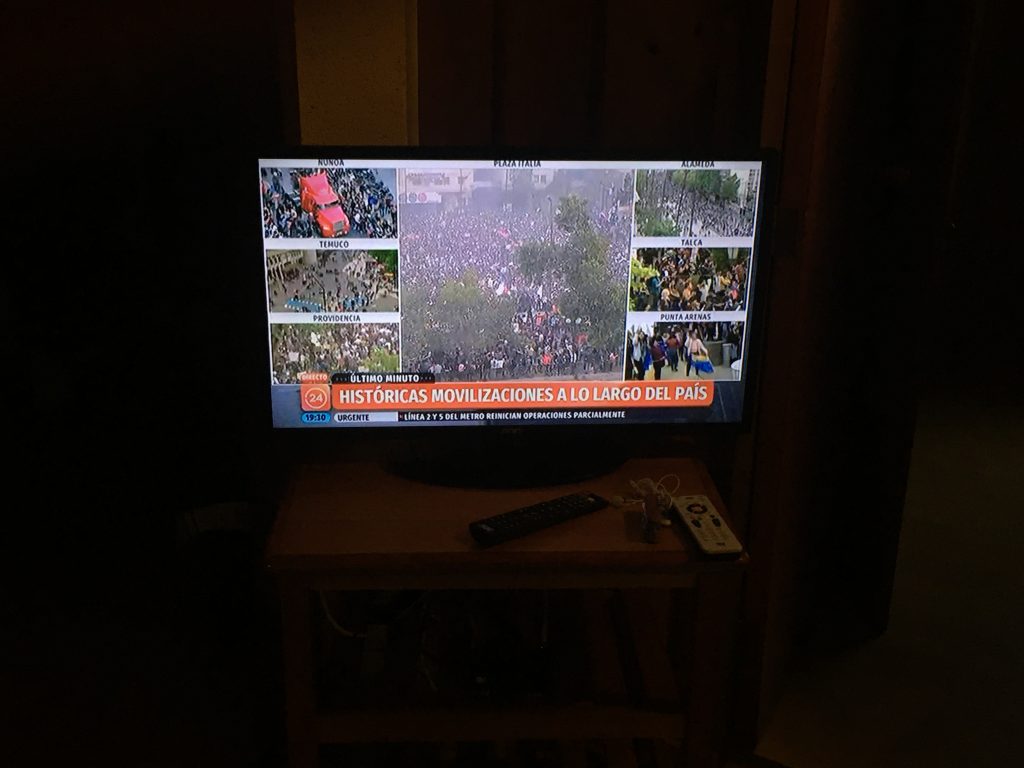

The people who know me know that I like to have everything planned out far in advance. Four year planning is one of my favorite things to do, and last minute planning stresses me out. Not knowing what’s going on stresses me out. However, I, along with everyone from my program and 18 million Chileans, am having a crash course in living in a state of constant uncertainty. A little over three weeks ago, nationwide protests began as a response to a raise in the price of the Santiago subway fare. In reality, the raise in the price became a symbol for the more than thirty years of high income inequality, privatization of everything (including the entire education system and access to water), and a lack of social programs to support the large number of Chileans making just above minimum wage. One of the many consequences of these protests has been the constant uncertainty that has been thrown over every aspect of life.

When the protests began, my program was on a trip to the countryside of the Araucanía, far removed from everything that was happening. The Santiago airport was closed for several days, and no one knew what was going to happen. Not a single person expected the protests to turn into the enormous movement that has emerged in the last several weeks. For the last week that we were there, we were living from day to day, not knowing what was going to happen, not knowing if we were even going to be able to go back to our host families in Valparaíso and Viña del Mar. Several days after we were originally supposed to go home, we finally made it back to our home base.

However, being back with our host families in our Chilean homes has done nothing to eliminate the day to day uncertainty of living in a situation of social unrest. When you walk down the street, you never know when a protest might spring up out of nothingness; whether roads are going to be open when you’re trying to get home; whether you’re even going to be able to make it to class that day. You can’t even begin to speculate what’s going to happen to the country at a national level because it changes from one minute to the next.

Genuinely, it’s very hard to live day to day, hour by hour, not knowing what’s going to happen in the afternoon, let alone what’s going to happen long term with the country. The stress manifests physically, and a lot of Chileans I’ve talked to are struggling to sleep, plagued with migraines and nausea, and constantly fatigued. I’ve noticed that as time goes on, I and the people around me have slowly adjusted to this new reality. We’ve learned to check social media to see what roads are closed and when/where protests are going to be before heading out. We know when to go into town, and when it’s better to stay home. We’ve become flexible with our plans and understanding of each other’s timing. The uncertainty has become a constant part of the context in which we live our lives, and, as with any context, the longer we move within it the more accustomed we get.