Editor’s note: The following, written by Humanities Librarian Patrick Morgan, is the second in a series about a book found within Van Wylen Library’s rare book collection. Read the first post here.

I would like to claim that the delay in writing up this second installment of the Armenian Gospel saga is due only to my refractory tendency to make things as dramatic as possible by building up suspense. In truth, the delay is uniquely attributable to my (also refractory) habit of procrastination.

To be fair, the delay in this particular case has much more to do with a craven desire to avoid making strong conclusions than native laziness. I would hate to look (more) foolish (than usual). As a result, I have been hoping that some kind of amazing, definitive realization would irrupt, like the benzene ring, during a dream. Or something like that.

Since this hasn’t yet happened, what I have ultimately decided to do is present a run-down of things as they currently are, as a sort of provisional set of hedgy conclusions. With any luck, someone might find this interesting.

When I left off last time, I was trying to find ways to arrive at a realistic estimation of the book’s age. Part of the reason I broke it off where I did was because of an uncomfortable awareness that the language issue dangles menacingly over any meaningful conclusions I might draw. That is to say, if I knew Armenian, it would likely be much simpler to date the manuscript(s). Since I don’t, the sensible thing to do would clearly be to locate and consult with someone who does. This would then obviate any of the other available routes to dating the text, provided indications of this were to be found among the marginalia.

So: why keep at it? Why make it so complicated?

I have my reasons. First, tracking down Armenian speakers is harder than it might seem. Second, I am (lately) in so-far inconclusive communication with such a person. This aspect of my understanding of the book’s mysteries remains inchoate. Additionally, it is important to bear in mind the fact that we have at least two different elements: the book as a whole and the manuscript alone, which may or may not share a birthdate. Since this is the situation, then, I have ultimately decided to approach this as a kind of game. Ooo.

Here’s what I intend to do. The remainder of this little post will present provisional conclusions regarding the book’s date. When (and if) firm linguistic evidence is brought to bear on the matter, these conclusions will either be (at least partially) corroborated or overridden. In the meantime, this provides a fine exercise in the use of a book’s material aspects as a means of dating in the absence of clear written indications.

The book was put together, in its current form, in the last quarter of the 17th century. It was probably bound in New Julfa, which is a suburb of Isfahan, Iran, near the Caspian Sea. These conclusions are drawn largely from binding style and cover decorations. Notably, the manuscript is not contemporary with the binding. Based on the script used in all four gospels, the most likely period of the text’s composition is somewhere around 1500. The whole thing, then, could have been bound multiple times over a two-century span – not an uncommon occurrence.

Cover

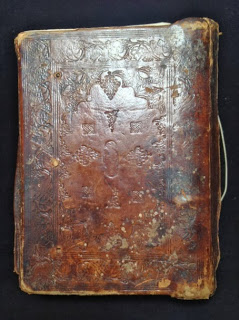

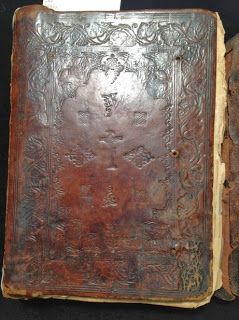

The [front] bears a small crucifix within a decorative floral frame, and the back has a tiny, debrided image of the Virgin Mary within an identical frame. A number of smaller abstract shapes occupy the field within both frames, more or less symmetrically arranged around the central figures. All impressions appear regular enough to have been done with stamping tools.

[back]

[front]

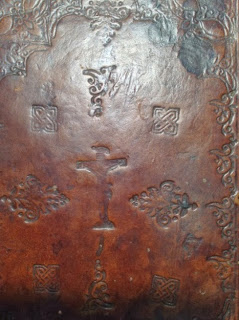

Here are close-ups of the impressions on the covers. The two most striking are those of the crucifix and rectilinear, rosettesque designs on the front, and the same rosettes surrounding the worn-down Virgin figure on the back.

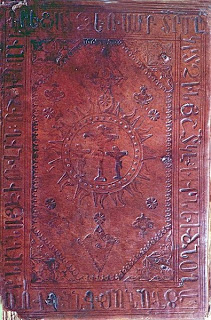

Compare those images to the one below. This is an image of the front cover of a similar gospel, dated to 1695. (The manuscript itself dates to the 14th century.) This is a good example of the New Julfa style of cover decoration, which departed from the older, simpler theme of a large braided cross. Hallmarks of this 17th-century style include the use of rectangular frames, floral patterns, and various stamps; each of these has been said to emulate Western decorative motifs. The crucifix and Virgin stamps are among the most common in this group. Note the similarity of the stamps below to that on our gospel, above.

[Photo by Dickran Kouymjian; Cf.: http://armenianstudies.csufresno.edu/arts_of_armenia/music.htm]

Our copy differs from several other examples of this style in a couple of obvious ways. Clearly, it lacks a cover inscription (you can see one in the example just above, dancing around the outermost frame). When present, they usually indicate the date of binding, and frequently name the binder and others associated with the book. Our copy also carries rectilinear rosettes instead of the circular forms above. While it may seem a tiny detail, the use of these provides yet another suggestive bit of evidence that our book was bound in 17th-century Isfahan, as these are less common elsewhere.

Script

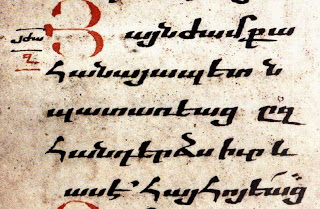

The ductus of the manuscript is itself a datable feature, though an imperfect one. Using the Album of Armenian Paleography – which includes detailed images and discussions of Armenian texts from nearly all periods within the long history of its alphabet, as well as a table of scripts organized chronologically and with reference to specific textual examples – it is pretty clear that our book was not written any later than about 1700 (based on the disappearance of certain letter forms), and no earlier than about 1400 (based on the appearance of certain letter forms). Dating something to within a three-century span is, I know, not very exciting. But get this: the texts with the most similar scripts were written between 1450 and 1501.

I am aware that arguing using this kind of information is dangerous when combined with my ignorance. Clearly, this is not stopping me. With that in mind, however, I have provided some comparative evidence below, a few images of these scripts so that you can make your own judgment. This, at least, should give you a rough idea of what I’m basing that claim on.

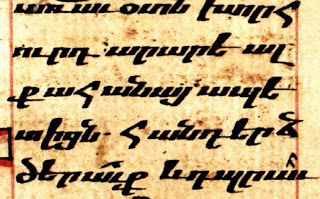

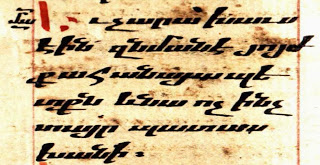

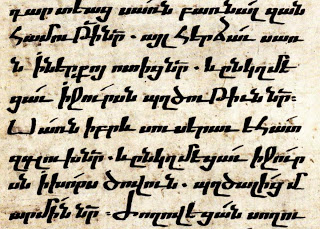

Here are a couple of samples of the text of our manuscript:

Certain aspects of the way this is written stand out. One of the more variable aspects of Armenian orthography – at least for this script, called bolorgir – is how the tails of certain letters curve. Ours could be described as “sharp,” a quality not always present in other texts. We can also look at the calligraphic aspects of letter formation: notice that in our text, bold strokes contrast with finer, thin lines within individual characters. More generally, the visual impact of the text can be distinctive. Some manuscripts from earlier or later use consistently rounder letter forms. Others escape the middle register more frequently, which creates a freer, less blocky effect. All of these variations, and more, occur within that single bolorgir style.

With some variation, the writing style used in our gospel is common between the 14th and 17th centuries. Certain elements of the text, such as marginal illustrations and ornithomorphic letters (letters made out of birds) can be found throughout this period, too. If our manuscript was bound in the middle to latter 1600s, then it seems safe to assign a roughly similar date to its composition. Considering both general “gestalt” elements as well as individual letter forms, however, our text is written most similarly to those written around the end of the 15th century. Below are a few examples.

[Ma XIII 38 – University Library, Tuebingen – 1465]

[Or 5476 – Leiden University – 1478]

[Chester Beatty 602 – 1489]

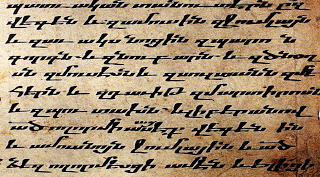

Despite some individual variation, I think you’ll notice strong similarities both in letter forms and in overall composition. To continue the comparison, here is a representative example of a rather similar 17th-century script.

[Matenadaran 3598 – 1624]

I suppose I ought to confess that I am having a very difficult time keeping my wishes from creeping into my conclusions. I am fighting hard. I mention this as a caveat; to me, the older scripts are much more similar, structurally and character-wise, to our text than are those contemporary with the binding. Following the advice of Dickran Koumjian – a well-known student of Armenian paleography, among other related things – script comparisons are still the best, if not a perfect, way to date individual manuscripts.

What else?

There are plenty of other angles we could explore to get a richer sense of this book and its age, but I’m not sure this article has left much space for them. We haven’t dealt with the marginal illustrations, for example, which have some peculiarities worth investigating. While abstract floral designs predominate, there are a few unexpected forms, two of them appearing within the same gathering, which might mean the participation of different writers. (We already know that many different people left notes in the margins, of course, but this would be another matter entirely). Then, of course, we would need to consider the possibility of age variation between parts of the manuscript, among other things. I don’t mean to do any injustice to complexities like these, but perhaps it is alright for now to leave those for future explorations.

I feel strongly that this little codex will provide ample fodder for others interested in book history for any reason. If you’d like to actually see it, we’d be quite glad to arrange that. Whether or not my conclusions are accurate, this book is a real treasure in our collection.

Kouymjian, D., 2013. “Notes on Armenian Codicology. Part 2. Armenian Palaeography: Dating the Major Scripts,” Comparative Oriental Manuscript Studies Newsletter no. 6 (July 2013), pp. 22-28.

Kouymjian, D., 2008. “From Manuscript to Printed Book: Armenian Bookbinding from the Sixteenth to the Nineteenth Century,” Printing and Publishing from the Middle East, Papers from the Second International Symposium on the History of Printing and Publishing in the Languages and Countries of the Middle East, Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, 2-4 November 2005, Philip Sadgrove, ed., Journal of Semitic Studies, Supplement 24, Oxford, 2008, pp. 13-21, 276-297 (plates).

Stone, M., Kouymjian, D, Lehmann, H., 2002. Album of Armenian Paleography. Copenhagen: Aarhus University Press.