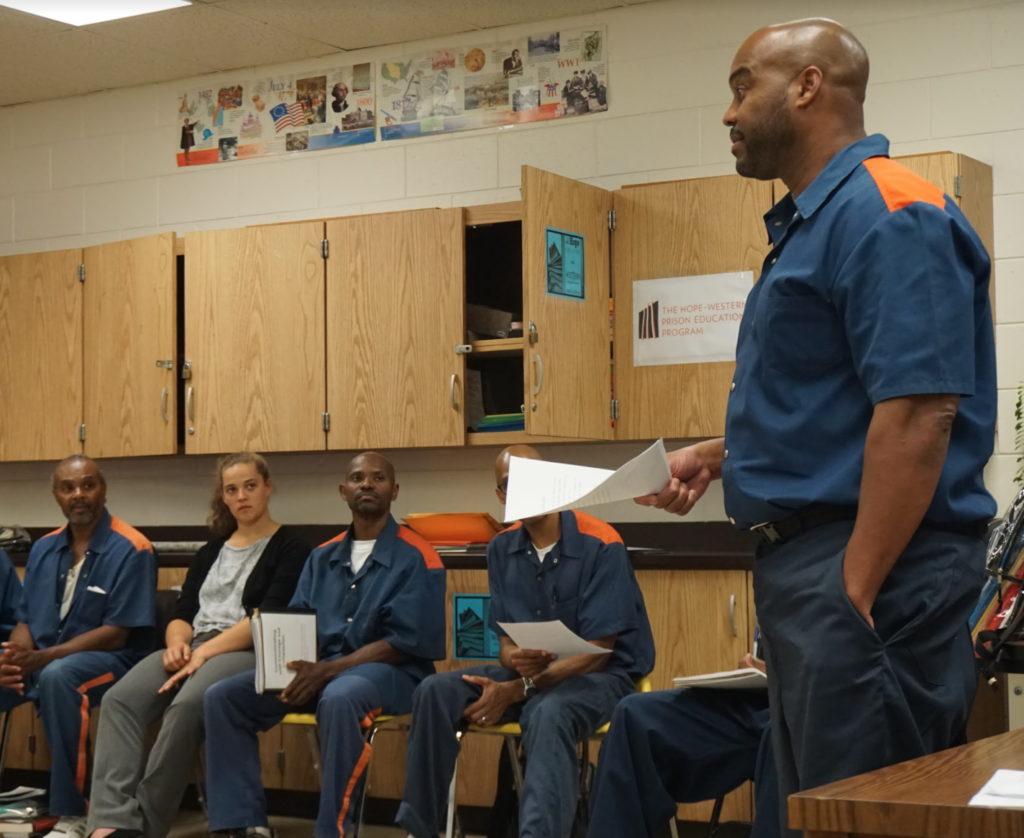

The Summer 2021 issue of News from Hope College features an article on the Hope-Western Prison Education Program.

The Summer 2021 issue of News from Hope College features an article on the Hope-Western Prison Education Program.

Today Hope College, Western Theological Seminary, and the Michigan Department of Corrections announced a six-year renewable agreement to offer a Hope BA at Muskegon Correctional Facility. Read more about it here>>

The Hope-Western Prison Education Program operated in a non-credit mode from March 2018 through July 2021. The 20 students in the program’s first cohort took six courses and engaged in two book studies in this pilot phase of the program. Here is what we learned:

Students

Proposition 1: Incarcerated men serving long sentences are capable of successfully completing college-level coursework.

Proposition 2: Incarcerated students can competently read, reflect critically, speak powerfully, and write cogently about challenging texts.

Proposition 3: Incarcerated students are capable of generative thinking and creative expression in different genres.

Proposition 4: Incarcerated students are capable of enlarging their imaginations for lives marked by significant personal, intellectual, and spiritual transformation.

Proposition 5: Traditional WTS and Hope students are interested and capable teaching assistants, and are deeply impacted by the experience.

Proposition 6: There is a high demand for the program.

Faculty

Proposition 7: Faculty have the personal and professional interest and capacity to teach an occasional course over and above their normal Holland-campus assignments.

Proposition 8: Faculty find inspiration and professional fulfillment in teaching in prison.

Proposition 9: Faculty can successfully modify their pedagogical methods to fit the constraints imposed by prison security rules.

Proposition 10: Faculty are willing to plan curriculum for prison-based courses consistent with the goals, objectives, and rigor of Holland-based courses.

Prison System

Proposition 11: MDOC and Muskegon Correctional Facility leadership is capable of accommodating HWPEP’s learning objectives within the context of their security and custody mandate.

Proposition 12: MDOC and Muskegon Correctional Facility leadership is committed to supporting and grateful for the presence of the Hope-Western Prison Education Program.

Proposition 13: MDOC and Muskegon Correctional Facility leadership is willing to commit the necessary planning time to ensure the program’s success.

Proposition 14: MDOC officials will advocate with Federal officials on behalf of the Hope-Western Prison Education Program.

Donors

Proposition 15: Friends of the college and seminary are interested in learning about the Hope-Western Prison Education Program.

Proposition 16: Friends of the college and seminary will partner financially to launch the program.

Proposition 17: The program’s purposes are “trans-partisan” and are supported by both political/theological conservatives and progressives.

HWPEP students are “proving it.”

Please consider a gift to support our work.

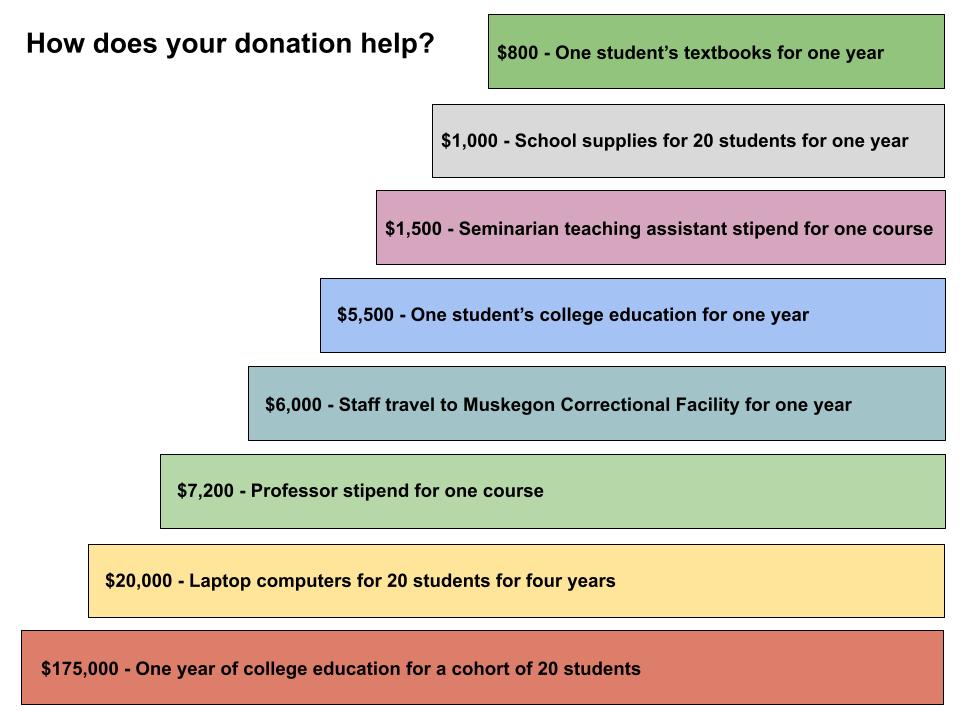

The Hope-Western Prison Education Program’s fundraising goal for 2022 is $200,000. Gifts made this year will be matched up to $100,000. All gifts help offset costs for professor and teaching assistant stipends, travel to and from Muskegon Correctional Facility, textbook and computer purchases, school supplies, and student and staff orientation. Can you help?

Visit us at www.hope.edu/hwpep

and

Read more at blogs.hope.edu/hwpep

Help us spread the good news of the Hope-Western Prison Education Program by forwarding this to a friend. Thank you.

Our mailing address is:

prisonprogram@hope.edu

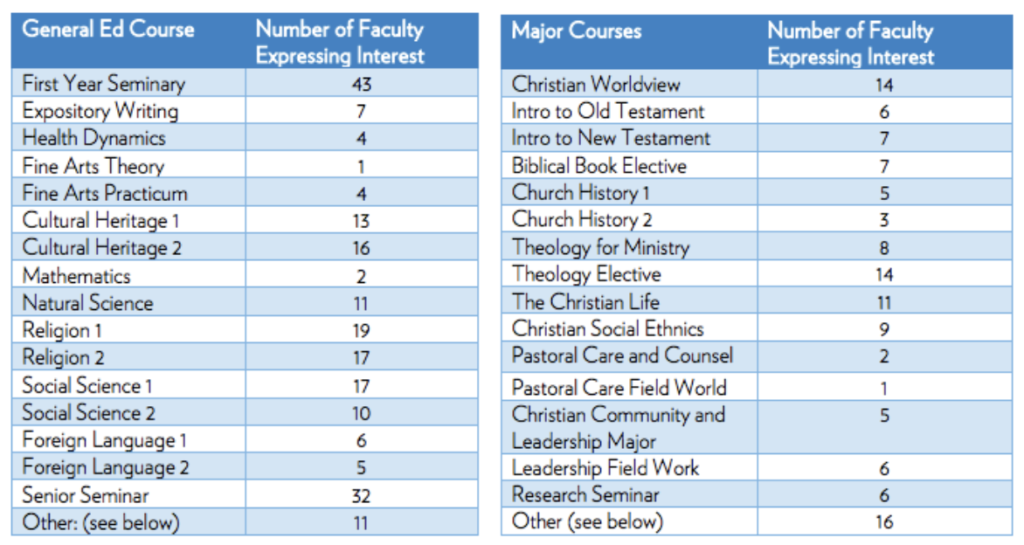

We surveyed the Hope and WTS faculty during the planning phase of the Hope-Western Prison Education Program. One hundred seventy-two faculty responded to the survey. Of the 147 that completed the survey, 61 (42%) of you responded affirmatively when asked if you would be interested in teaching in the program. Forty of you (27%) indicated that you might be interested depending on your personal circumstances at the time. Forty-six respondents (31%) were not interested at the time (2018), though the reasons provided were typically circumstantial and temporary.

We have a much more compelling story to tell now that six courses have been completed at Muskegon Correctional Facility. Take a look at this and see if you don’t find your imagination stirred:

Will you join us? Send us a note at prisonprogram@hope.edu. Let’s talk.

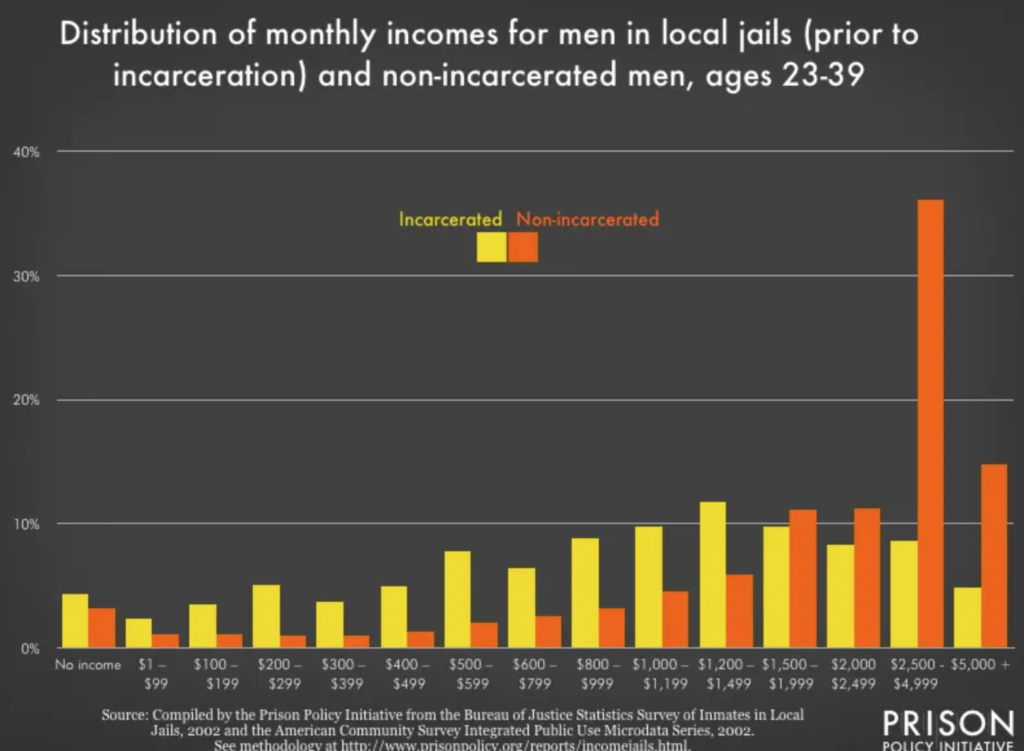

The question may seem silly to those of us for whom a college education was always part of our natural path to full adulthood. But many incarcerated people come from backgrounds of poverty, violence, and trauma. The kind of future-oriented imaginations that most of our traditional students grow up with are foreign to people whose idea of “the future” only extends to the end of the day.

Just getting by.

Just getting through the day.

Go to college? Probably not.

We recently interviewed three graduates of the Calvin Prison Initiative. Each has been paroled. Each is now putting his college education to good use. Each is a productive and engaged member of his community. We asked these men why they decided to go to college in prison. Hear what they had to say.

The parable of the widow’s mite (Luke 21:1-4) is familiar to many. An impoverished widow contributes two small coins as an offering to the temple coffers. These coins represent a huge sacrifice for her. We can imagine her praying “Take all that I have, Lord, for all I have is yours.”

The Hope-Western Prison Education Program has received many gifts to support the work of educating its students. All gifts are meaningful not only for how they push the HWPEP mission forward, but for how they connect the givers to our students in real, tangible ways. Some gifts have been sizable and sacrificial. But some have been small and sacrificial.

Consider the way one HWPEP student gives sacrificially to the members of his imprisoned community:

“I cook meals for brothers every now and then. I also was led to start a birthday ministry where I give guys candy bars, popcorn, and other food items on God’s behalf for their birthdays.”

Candy bars, popcorn, and “other food items” are luxury goods in prison. We take them for granted. This student does not. Note that he provides these things to his friends “on God’s behalf.” This student goes without so his brothers can have a little.

There is another student who was admitted to the first cohort in 2018. He took two HWPEP courses, and did well. He was quick to raise his hand to contribute to class conversations. His smile, cheerful attitude, and sense of eager inquiry was infectious. He has since been transferred to another prison so he can pursue an Associate’s degree from a college with a more established program.

This student has written to us on three occasions. The envelopes containing his letters were immaculately composed. Each contained a first-class stamp carefully affixed in the upper right corner of the envelopes. These stamps cost 55 cents – a princely sum for someone who earns mere pennies per hour for his prison job.

And each letter was accompanied by a check for $10.

Imprisoned people are poor. Most were poor when they went to prison, they remain poor while incarcerated, and they are poor when released from prison. The student who contributed $10 (three times!) to HWPEP is poor. He has given from his need. Here’s what he wrote with his latest contribution:

“God bless your Hope campus in Holland! This year has not started off easy, however, I have a personal testimony to share with you. As an agent of hope, my trust in God has been renewed by the passing of my Christian mother on January 8. Christ’s life is manifested in the sacred heart of our Heavenly Father and Jesus – in the blessed hope and rest of the faithful. Looking back at our time together in a small classroom at Muskegon Correctional Facility, I still remember my mother being happy that I was part of a Christian liberal arts college, not just a school teaching me how to make money…”

These incarcerated students’ mites honor God. They encourage us. They humble us for the work that Hope and WTS professors are doing to elevate their students’ lives. And their own.

(And what to bring when you do)

On Good Friday we read in Isaiah:

He was spurned and avoided by people,

Is 53:3,8

a man of suffering, accustomed to infirmity,

one of those from whom people hide their faces,

spurned, and we held him in no esteem… Oppressed and condemned, he was taken away, and who would have thought any more of his destiny when he was cut off from the land of the living…

Did I think of the Suffering Servant as this reading was proclaimed? Sure, but my mind drifted to a group of men 45 minutes up the road. Men incarcerated at Muskegon Correctional Facility. Men who hope to one day earn a Hope College degree. Men who are spurned, avoided, cut off. Condemned.

Jesus tells his followers this:

Then the King will say to those on his right, ‘Come, you who are blessed by my Father; take your inheritance, the kingdom prepared for you since the creation of the world. For I was hungry and you gave me something to eat, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you invited me in, I needed clothes and you clothed me, I was sick and you looked after me, I was in prison and you came to visit me.’

Mt. 25:31-36

But why? Why does Jesus, the Suffering Servant, include visiting the prisoner among the corporal works of mercy? The other categories seem rather obvious because of their universality. Giving food to the hungry helps with their hunger, and most of us have experienced hunger, even briefly. Giving water to the thirsty helps with their thirst, and we’ve all been thirsty, even briefly. A gift of clothing keeps the naked warm and preserves their modesty, and we all know what it feels like to be cold and ashamed. But prisoners? Probably not. They’re beyond our experience.

Michael Van Sloun has this to say:

Jesus has mercy for “the least,” those despised by others. Convicts rank high among “the least.” For the general public, when a criminal gets prison time, the criminal is getting what is deserved; the criminal needs to pay for what has been done. Jesus understands the brokenness of those who have done hateful things. From the cross Jesus said, “Father, forgive them, they know not what they do” (Lk 23:34). Jesus wants us to have compassion for those in jail or prison. Instead of having an attitude of anger, retribution, punishment or vengefulness, Jesus wants us to be merciful. We need to honestly acknowledge our own inclination to evildoing and admit, “There, except by the grace of God, go I.” Prison time is hard time. It is lonely time. It is dangerous time. Prisoners need help, support, encouragement and prayers. And as Jesus explained, a visit is a great way to help a prisoner.

R.J. Snell helps us center the idea of what it means to “do good” in our modern times, with its evolved understanding of justice:

Justice is not enough; mercy and forgiveness are also required. Evil is repaid with goodness, not in a way which denies justice but in “a manner unexpected by reason itself.” Aristotle has no category for redemption, no expectation that the vicious man could enjoy beatitude. Consequently, the Christian sees both more wretchedness and more exaltation in the human condition than did the Greeks, believing in both original sin and the incarnation. All men are grass, all sinful, and yet all are created in the image of God and all are offered a share in the divine glory through the startling fact of Easter. No one is beyond redemption, no one disposable.

The parable in Matthew 25 suggests that mercy requires “product and presence.” “Doing for” and “being with.” We bring food to the hungry. We bring drink to the thirsty. We bring medicine to the sick, and clothing to the naked. We help the homeless find shelter. But what do we bring the prisoner? More specifically, what do we at Hope College and Western Theological Seminary bring the prisoner? We bring what we have: The product of our years in graduate school, years of teaching experience, and understanding of discovered and revealed truth. We bring the product of our institutional missions:

By God’s grace, Western Theological Seminary forms women and men for faithful Christian ministry and participation in the Triune God’s ongoing redemptive work in the world.

The mission of Hope College is to educate students for lives of leadership and service in a global society through academic and co-curricular programs of recognized excellence in the liberal arts and in the context of the historic Christian faith.

This is what we have. This is what we bring: Our own presence which dignifies and respects those in prison. We bring education and formation that gives them an opportunity to grow in their faith, leadership abilities, and capacity for service.

This is how we acknowledge the prisoner’s kinship to the Suffering Servant.

One of our goals during Covidtime is to send learning materials and assignments to our Hope-Western Prison Education Program students at Muskegon Correctional Facility. We hope to maintain a learning community and develop habits of continuing intellectual engagement. Keeping in touch with these students in this way is especially important while we aren’t allowed to teach face-to-face. And no, there’s no Internet in prison.

One idea we’ve had is to create a book club. We’ll send the students a book and some possible discussion questions. They’ll be encouraged to read the books and discuss them with their peers – both students admitted to the program and other incarcerated peers. These won’t be academic courses per se. They won’t require any written assignments. They’re meant to keep students talking to each other about ideas. And to help them enjoy reading.

Suggest a book or two for us to consider. What do you recommend? Use the comment feature or e-mail us at prisonprogram@hope.edu. We’d be grateful for your help. And our students will be even more grateful. Thank you.

There is more creative spirit and talent among incarcerated people than you might think.

Check out the special exhibition of artworks by incarcerated and formerly incarcerated artists at MoMA PS1 in New York. Concluding April 4, the exhibition can be viewed virtually through the Bloomberg Connects app. Marking Time: Art in the Age of Mass Incarceration is the product of 35 artists – each of whom has experienced the prison system. You can read a review by Griffin Oleynick here.

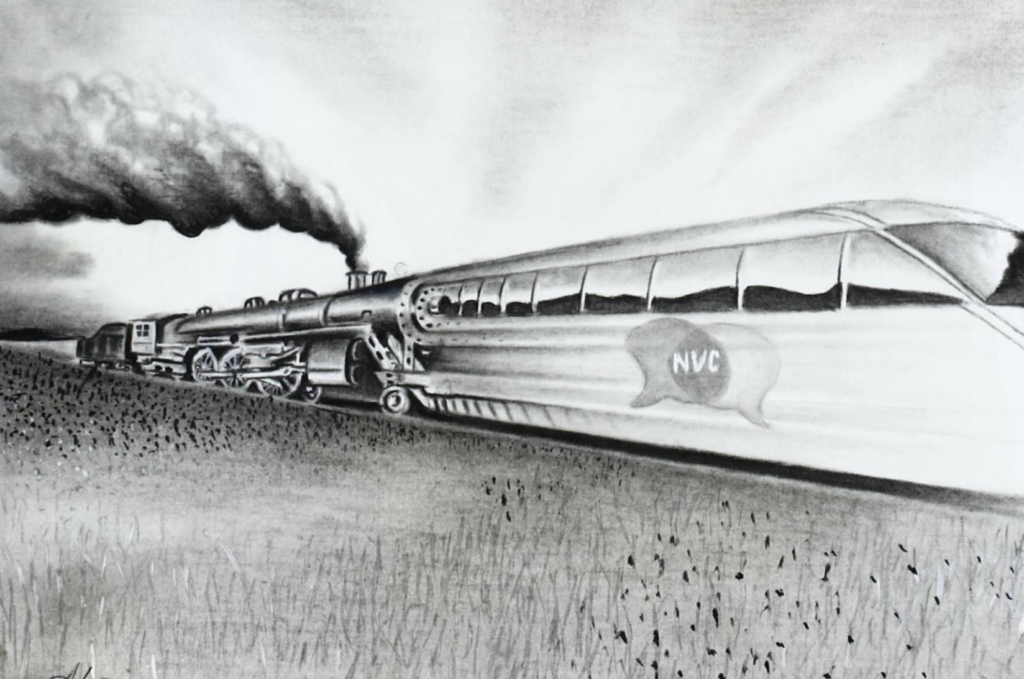

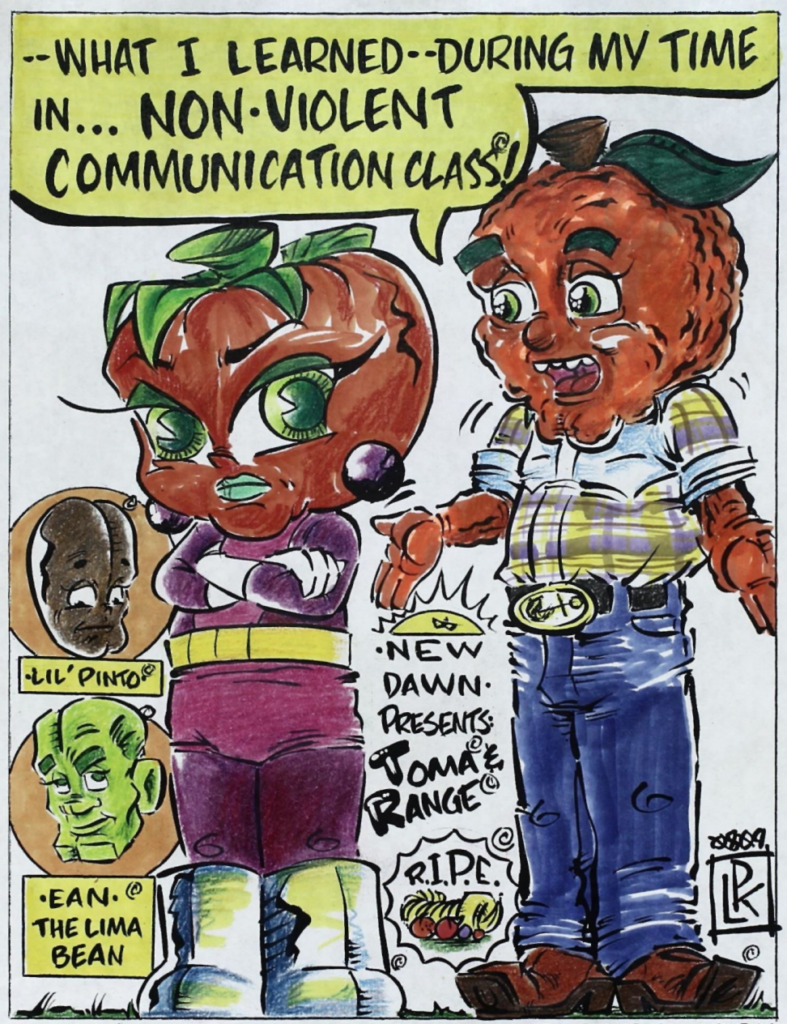

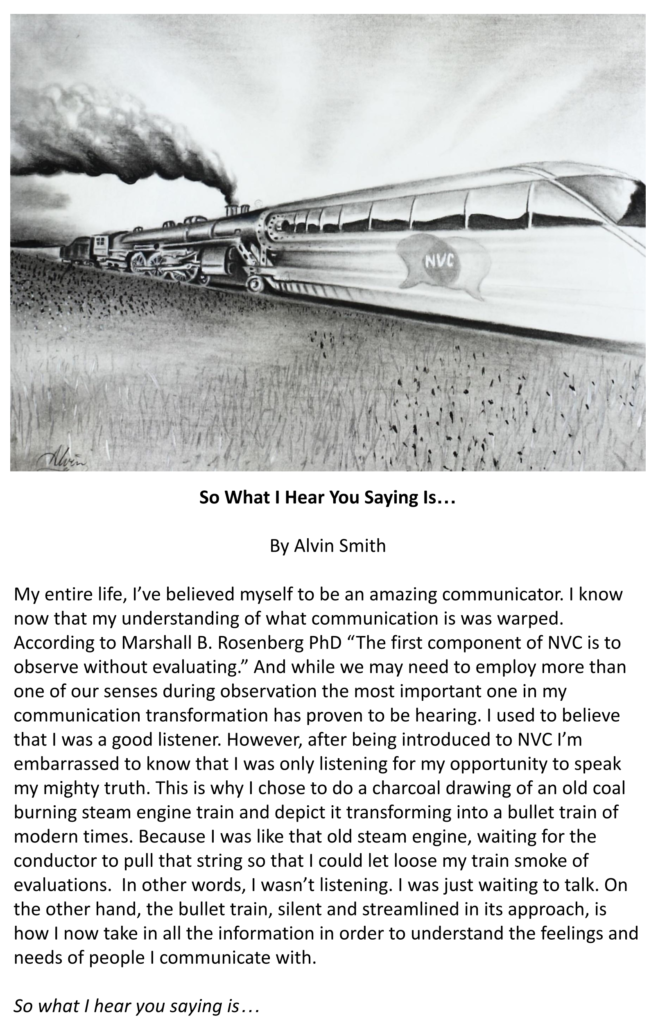

Two of our Hope-Western Prison Education Program students are talented visual artists. Here are a few examples of their work.

These two works were created as part of a final project in Professor Pam Bush’s Communicating With Courage and Compassion course, and summarize the student-artists’ transformation through non-violent communication: